The Healing Power of Fiction, a guest post by Nora Shalaway Carpenter

I am passionate and outspoken about authentic, non-stereotyped mental health representation in young adult literature. To explain why, let me tell you story.

When I was diagnosed with trauma-induced, severe obsessive compulsive disorder and PTSD, my husband and I confided in our immediate family. Here are some of their initial responses:

“Just think about happy things. You can do it!”

Blank stares and silence.

“You’re going to hurt the baby!” (I was carrying our first child at the time.)

“What you went through was for the best, in the long term. You’re lucky.”

About a month later, a family member took me out to lunch. As I sat in the restaurant, barely holding myself together, she told me: “It’s time to stop this now. You have to snap of it.”

Let me translate that from the point of view of an individual suffering with mental health: You are behaving this way on purpose. You’re choosing to be miserable all the time. If you were stronger, you wouldn’t be like this.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Although I still haven’t completely recovered from the emotional damage that statement caused, my relative is far from alone in that view. Her Appalachian culture (the culture I grew up in as well) instills a “yank yourself up by your own bootstraps” mentality almost from birth. Mental strength is a prized (and expected) attribute. If you’re not in tip top mental shape all the time, you bury that fact where it will never see the light of day because it’s a source of shame not only for you, but for your entire family.

Again, such mentality is not unique to Appalachian culture. Similar ideas cross myriad backgrounds, cultures, and socio-economic classes: that only “weak” or “insane” people suffer with mental health; that mental health struggles are imagined and not actually real; that medication to treat them is somehow shameful whereas medication for physical illnesses is a no-brainer.

After the disappointing reactions from my family, I tried one more lifeline: a close friend who was almost a second mom to me. And though she looked sad, she also looked bewildered, like I had spoken a different language. “Tell me what you need,” she said, trying to be helpful. And I know she was genuine, that she was asking because she truly didn’t know.

It turns out, people in crisis can rarely articulate what they need, but I didn’t know that at the time. Instead I felt stupid for not knowing and guilty for making her feel awkward. I left as soon as I could.

Suffice it to say, I didn’t tell anyone else what was happening with me. If family members and a trusted confident couldn’t handle it, I reasoned my peers would probably ditch me immediately. Even with a diagnosis, it took a long time to get me on the correct treatment plan, so I spiraled into a very dark place. I couldn’t touch the dog I used to snuggle with every day because my brain told me he might carry germs that could hurt my unborn baby. I couldn’t use a public bathroom. I couldn’t handle raw meat anymore because what if I didn’t wash my hands well enough and I made someone sick? I checked and rechecked and checked again that the stove was off…and then I wasn’t sure if I’d checked. And once—one of my most vivid memories from that time—I literally couldn’t stop washing my hands and arms and had to call my husband downstairs to help me turn off the water.

I was terrified of getting out of bed each day because of all the triggers I’d endure while awake. I put all of my suffering focus into graduate school (it was low-residency, thank goodness, so mostly online) and I stopped hanging out with friends.

One day, one of them asked me to grab tea with her, and because I hadn’t seen her in a while and was determined to overcome my horrible disease by sheer force of will, I agreed. As we sat sipping our drinks, she gently told me she knew something was wrong. That I could talk to her. I was mortified. I’d tried so hard to hide all my symptoms, to appear normal. But I couldn’t do it any longer. Everything spilled out—the trauma, the diagnosis, the way I couldn’t control the wild, spinning thoughts in my head that made me feel like I was slowly losing my mind.

As much as the “snap out of it” reaction is seared into my memory, so too is my friend’s response. She didn’t tell me I could fend off OCD with positive thoughts. She hugged me so that I felt in my bones she would never abandon me in this; she would never run away from this ugliness. She cried with me, right there in public. It was the first time someone (apart from my husband) didn’t imply that my OCD was in some shape or form my fault.

It is not an overstatement to say that proper treatment (for me, serotonin and cognitive behavioral therapy), both of which I never would have received or accepted without the support of important friends, saved my life.

I’m a writer, so as I began to heal, I knew that in order to process what I’d been through, I had to write about it—not the actual, real life details of my personal situation, but the feelings and emotions the experience brought out: the utter despair that I’d somehow brought this on myself and would never again be okay. That I wasn’t trying hard enough to get better. That despite having loving people around me like my husband, I was totally, horrifyingly alone.

I also wanted to explore the kind of friendship that could pull a person through such a hellish experience, and how such a friendship is established.

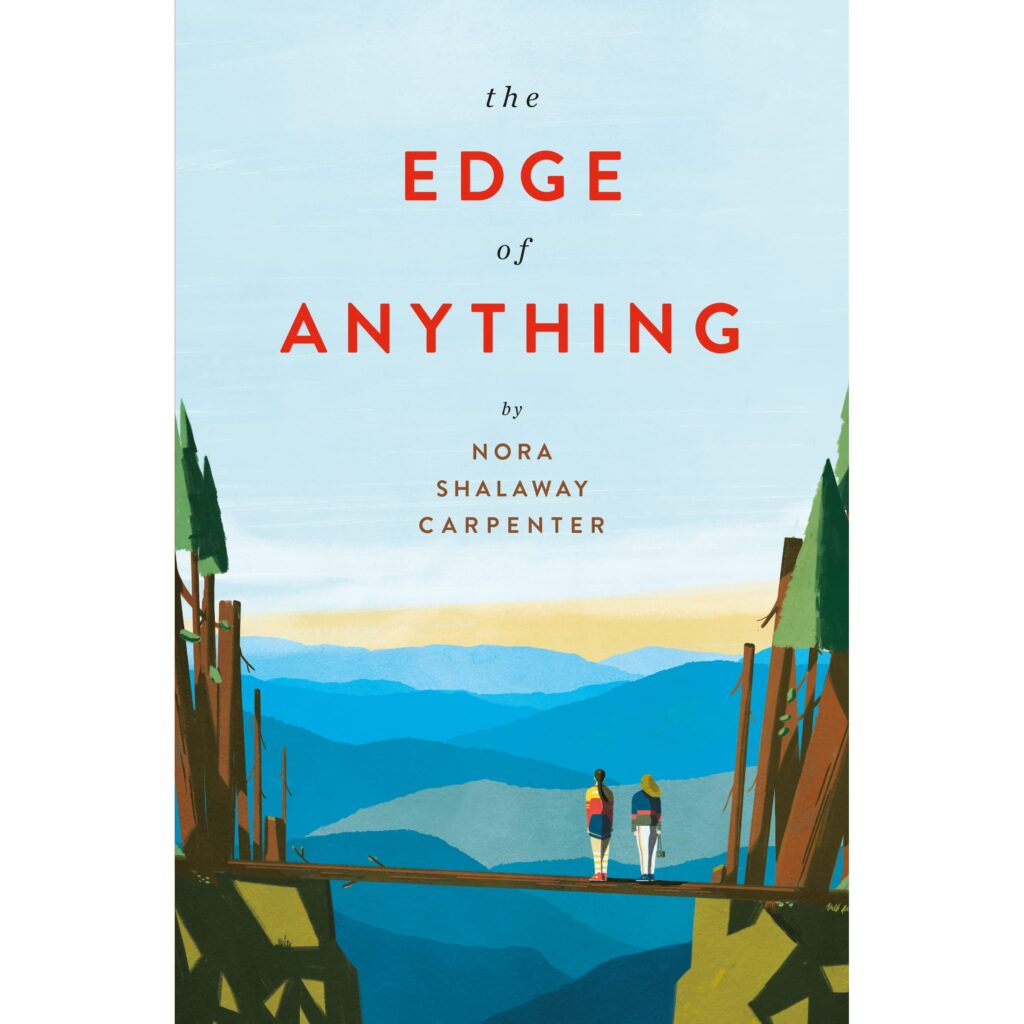

The Edge of Anything is the book I’d longed for during my own darkest days. It tells the dual narrative of two teenagers—one a shy photographer unknowingly suffering a mental health crisis, the other a popular volleyball star with her own devastating secret—and the unexpected friendship that saves them both.

The book stars teenagers because I’m a young adult author, but also because teenagers are one of the most vulnerable populations when it comes to mental health. Sadly, according to recent statistics, one out of every five teenagers suffer from at least one mental health disorder per year[i], and the rate of depression in adolescents aged 12-17 has increased 63 percent since 2013[ii]. What’s more, seven-in-ten teens see anxiety and depression as “major problems among their peers.”[iii] When I think about how difficult it was for me, as an adult with health care and a supportive spouse, to figure out what was happening and find a health care specialist who understood what I was going through, the thought of undergoing a similar experience as a teen is devastating.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Today, I can tell people I have OCD. More than once someone has confided in me about their own struggles (or those of someone they care about) and I’ve been able to help them a tiny bit on their journey. Because communication matters. It can change and save lives.

It’s my hope that The Edge of Anything will function in a similar way for readers, both those all-too-familiar with mental health struggles and those with no personal experience. No one needs to be told life isn’t fair. But I think we do all need to hear that sometimes we are not okay, and that itself is okay and not something that should shame or devalue a person. We are all loveable and beautiful—just as we are, even if we are undergoing a serious, behavior-altering health condition. And we all need to hear that there’s hope.

[i] https://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/adolescent-development/mental-health/adolescent-mental-health-basics/index.html

[ii] https://www.newportacademy.com/resources/mental-health/teen-depression-study/

[iii] https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2019/02/20/most-u-s-teens-see-anxiety-and-depression-as-a-major-problem-among-their-peers/

Meet Nora Shalaway Carpenter

A graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts’ MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults program, Nora Shalaway Carpenter is the author of THE EDGE OF ANYTHING, contributing editor of RURAL VOICES: 15 AUTHORS CHALLENGE ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT SMALL-TOWN AMERICA (Candlewick, Oct 13, 2020), and author of the picture book YOGA FROG (Running Press). Originally from rural West Virginia, she currently lives in Asheville, North Carolina with her husband, three young children, and the world’s most patient dog and cat. Learn more at noracarpenterwrites.com, @noracarpenterwrites on Instagram, and @norawritesbooks on Twitter.

Nora’s local indie is Malaprop’s Books in Asheville, NC. Order her book there!

About The Edge of Anything

A vibrant #ownvoices debut YA novel about grief, mental health, and the transformative power of friendship.

Len is a loner teen photographer haunted by a past that’s stagnated her work and left her terrified she’s losing her mind. Sage is a high school volleyball star desperate to find a way around her sudden medical disqualification. Both girls need college scholarships. After a chance encounter, the two develop an unlikely friendship that enables them to begin facing their inner demons.

But both Len and Sage are keeping secrets that, left hidden, could cost them everything, maybe even their lives.

Set in the North Carolina mountains, this dynamic #ownvoices novel explores grief, mental health, and the transformative power of friendship.

ISBN-13: 9780762467587

Publisher: Running Press Book Publishers

Publication date: 03/24/2020

Age Range: 13 – 18 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#206)

“Complex social dynamics exist in the simplest of conflicts.” A Kyle Lukoff Interview on Sorry You Got Mad

UnOrdinary | Review

ADVERTISEMENT

This is a beautiful article on an important topic. Thank you, Nora Carpenter!

I’m so glad you enjoyed it. Thank you for reading.

Hope and faith act as a virtual medicine for the one who is depressed or going through some mental health issues. Thanks, Nora for this beautiful and encouraging guest post which will surely encourage many to not lose heart when things are not working right. We all need to give time some time to make everything fine. This is a lovely book that must be read by each one of us to see positivity in every situation.

Thank you so much!

Thank you for writing so eloquently about such a tough subject.

Thank you for reading!