From Our Mailbox: #MHYALit and POC

A couple of weeks ago we opened our inbox to see there was a request for titles on mental health that featured POC characters. A brief scan of the #MHYALit Discussion index proved that we didn’t have a good resource for this. Karen, Ally, and I are always talking about what book lists we’d like to see done and what guest posts we’re hoping to find to fill gaps in our project. Before we jump into our post, a communal effort, let us just take a second to say that we are ALWAYS looking for more guest posts and more voices for this project. We have had so much great feedback and seen so many wonderful and important posts throughout the year. We try to pop up on Twitter every now and then putting out calls for more posts.

A couple of weeks ago we opened our inbox to see there was a request for titles on mental health that featured POC characters. A brief scan of the #MHYALit Discussion index proved that we didn’t have a good resource for this. Karen, Ally, and I are always talking about what book lists we’d like to see done and what guest posts we’re hoping to find to fill gaps in our project. Before we jump into our post, a communal effort, let us just take a second to say that we are ALWAYS looking for more guest posts and more voices for this project. We have had so much great feedback and seen so many wonderful and important posts throughout the year. We try to pop up on Twitter every now and then putting out calls for more posts.

So, in case it’s not clear, let us repeat it again: We’d love to get some more guest posts lined up, particularly posts offering intersectional and diverse views. Find any of us on Twitter (@TLT16, @aswatski1, and @CiteSomething), leave us a comment here, or send us an email (found here). Posts can be on any topic related to mental health.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

That said, let’s jump back to our mailbox question and titles on mental health featuring POC.

While doing some research we came across these facts regarding mental health:

- African-American adults are 20% more likely to report serious psychological distress than Caucasian adults.

- Older Asian-American women have the highest suicide rate of all women who are 65+ years old in the United States.

- Adults with disabilities are 3 times more likely to commit suicide than peers without disabilities.

- Gay and bisexual men have higher prevalence of eating and body image disorders than heterosexual peers.

- Individuals in poverty are more likely to be exposed to complex trauma and less likely to receive quality mental health services. (Source: Pinerest.org)

Which is why we put out the call once again for more #MHYALit guest posts with intersectionality. For example, the upcoming Afterward by Jennifer Mattheiu shows us a poorer family with a child on the ASD spectrum who suffers from trauma and his family is not able to get him the therapy he needs and it is directly contrasted with a wealthier victim of trauma who can and does get access to good therapy.

I (Karen) want to point out that one other important thing that I learned while researching this list is that there is much more stigma in minority communities regarding mental health. See, for example, The Stigma of Mental Illness in Communities of Color on NPR. Because of this stigma, people of color are much less likely to seek out treatment, which means it’s even more important that we have more diversity in our mental health titles so that we can help normalize the discussion and let teens of color know that they are not alone in their struggles and they can get good care and support.

Upon discussion, we realized that it was harder to brainstorm titles then we could have imagined. But we got back to the request with a promise that we would post a list soon and a thank you for reminding us to make sure we were addressing diversity. After doing some research and looking at our own reading lists, we came up with a beginning list. It’s a woefully small list and if you have titles to recommend, please add them in the comments. Rather than repeat titles, for a very thorough look at Depression in YA and the Latin@ Community, please see the excellent post by Cindy Rodriguez on Latinxs in Kid Lit.

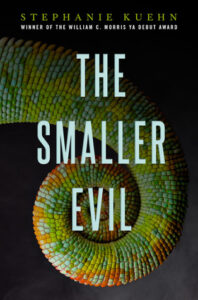

Anything by Stephanie Kuehn

Stephanie Kuehn is a post-doctoral fellow in psychology and she writes excellent YA literature. You can find good discussions of mental health in any of her titles. Her most recent title, The Smaller Evil, comes out August 2nd. She talked about it some in this previous #MHYALit Post. Make no mistake though, you should read all of her titles: Charm and Strange, Complicit and Delicate Monsters are her previous titles.

Publisher’s Book Description for The Smaller Evil

Sometimes the greater good requires the smaller evil.

17-year-old Arman Dukoff is struggling with severe anxiety and a history of self-loathing when he arrives at an expensive self-help retreat in the remote hills of Big Sur. He’s taken a huge risk—and two-thousand dollars from his meth-head stepfather—for a chance to “evolve,” as Beau, the retreat leader, says.

Beau is complicated. A father figure? A cult leader? A con man? Arman’s not sure, but more than anyone he’s ever met, Beau makes Arman feel something other than what he usually feels—worthless.

The retreat compound is secluded in coastal California mountains among towering redwoods, and when the iron gates close behind him, Arman believes for a moment that he can get better. But the program is a blur of jargon, bizarre rituals, and incomprehensible encounters with a beautiful girl. Arman is certain he’s failing everything. But Beau disagrees; he thinks Arman has a bright future—though he never says at what.

And then, in an instant Arman can’t believe or totally recall, Beau is gone. Suicide? Or murder? Arman was the only witness and now the compound is getting tense. And maybe dangerous.

As the mysteries and paradoxes multiply and the hints become accusations, Arman must rely on the person he’s always trusted the least: himself.

Pointe is a complex and riveting story about a young ballerina whose world was rocked when her best friend went missing. Years later he returns and everyone is left dealing with the effects of tragedy. Pointe also deals with eating disorders, which are far too common in the world of dance.

Publisher’s Book Description for Pointe

Theo is better now.

She’s eating again, dating guys who are almost appropriate, and well on her way to becoming an elite ballet dancer. But when her oldest friend, Donovan, returns home after spending four long years with his kidnapper, Theo starts reliving memories about his abduction—and his abductor.

Donovan isn’t talking about what happened, and even though Theo knows she didn’t do anything wrong, telling the truth would put everything she’s been living for at risk. But keeping quiet might be worse.

Tiny Pretty Things by Sona Charaipotra and Dhonielle Clayton

Tiny Pretty Things by Sona Charaipotra and Dhonielle Clayton

Tiny Pretty Things is the first book in a duology. The second book, Shiny Broken Pieces came out earlier this year. It also focuses on the world of dance and shares the story from the point of view of three different characters in alternating chapters. In this book, characters deal with eating disorders, addiction and the stress that comes from wanting to be the very best in the highly competitive world of dance.

Publisher’s Book Description for Tiny Pretty Things

Gigi, Bette, and June, three top students at an exclusive Manhattan ballet school, have seen their fair share of drama. Free-spirited new girl Gigi just wants to dance—but the very act might kill her. Privileged New Yorker Bette’s desire to escape the shadow of her ballet star sister brings out a dangerous edge in her. And perfectionist June needs to land a lead role this year or her controlling mother will put an end to her dancing dreams forever. When every dancer is both friend and foe, the girls will sacrifice, manipulate, and backstab to be the best of the best.

Not Otherwise Specified by Hannah Moskowitz

Not Otherwise Specified by Hannah Moskowitz

(From Amanda’s 2014 SLJ review)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

High school junior Etta juggles many identities, none of which seem to fit quite right. She’s bisexual, but shunned by her group of friends, the self-named Disco Dykes, who can’t forgive her for dating a boy. She has an eating disorder, but never weighs little enough to qualify as officially anorexic. She’s a dancer, but just tap these days, not ballet, because as a short, curvy, African American teen, she doesn’t seem to have the right look for ballet. She feels like she’s never enough—not gay enough, straight enough, sick enough, or healthy enough. More than anything, she just wants to get out of Nebraska and hopes auditioning for the prestigious Brentwood arts high school will be her ticket to New York. A rehearsal group introduces her to Bianca, a quiet (and extremely sick) 14 year old from her eating disorder support group. Together, they prepare for the auditions and form a surprising friendship, one that embraces flaws, transcends identities, and is rooted in genuine caring. Moskowitz masterfully negotiates all of the issues, never letting them overwhelm the story, and shows the intersectionality of the many aspects of Etta’s identity. The characters here are imperfect and complicated, but ultimately hopeful. Moskowitz addresses issues like biphobia, race, class, privilege, friendship, and bullying in ways that feel organic to the story. Etta’s candid and vulnerable narrative voice will immediately draw in readers, making them root for her as she strives to embrace her identity free from labels and expectations.

Publisher’s Book Description of Not Otherwise Specified

Etta is tired of dealing with all of the labels and categories that seem so important to everyone else in her small Nebraska hometown.

Everywhere she turns, someone feels she’s too fringe for the fringe. Not gay enough for the Dykes, her ex-clique, thanks to a recent relationship with a boy; not tiny and white enough for ballet, her first passion; and not sick enough to look anorexic (partially thanks to recovery). Etta doesn’t fit anywhere— until she meets Bianca, the straight, white, Christian, and seriously sick girl in Etta’s therapy group. Both girls are auditioning for Brentwood, a prestigious New York theater academy that is so not Nebraska. Bianca seems like Etta’s salvation, but how can Etta be saved by a girl who needs saving herself?

The latest powerful, original novel from Hannah Moskowitz is the story about living in and outside communities and stereotypes, and defining your own identity.

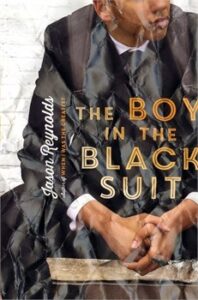

The Boy in the Black Suit by Jason Reynolds

The Boy in the Black Suit by Jason Reynolds

We’ve gone back and forth with authors and each other discussing whether or not grief could, would, or should fall under the umbrella of mental health. Where you fall in this discussion probably depends a lot on your own experience of grief. For many people, grief can present itself as a period of situational depression. The Boy in the Black Suit is a moving story of one young man’s journey through grief.

Publisher’s Book Description of The Boy in the Black Suit

Just when seventeen-year-old Matt thinks he can’t handle one more piece of terrible news, he meets a girl who’s dealt with a lot more—and who just might be able to clue him in on how to rise up when life keeps knocking him down—in this wry, gritty novel from the author of When I Was the Greatest.

Matt wears a black suit every day. No, not because his mom died—although she did, and it sucks. But he wears the suit for his gig at the local funeral home, which pays way better than the Cluck Bucket, and he needs the income since his dad can’t handle the bills (or anything, really) on his own. So while Dad’s snagging bottles of whiskey, Matt’s snagging fifteen bucks an hour. Not bad. But everything else? Not good. Then Matt meets Lovey. She’s got a crazy name, and she’s been through more crazy than he can imagine. Yet Lovey never cries. She’s tough. Really tough. Tough in the way Matt wishes he could be. Which is maybe why he’s drawn to her, and definitely why he can’t seem to shake her. Because there’s nothing more hopeful than finding a person who understands your loneliness—and who can maybe even help take it away.

Filed under: #MHYALit

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Moral Dilemma of THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

K is in Trouble | Review

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT

I’d like to suggest adding Boy21 by Matthew Quick to the list.