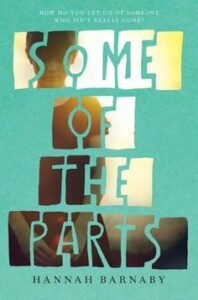

#MHYALit: A Place Where I Know: Writing About Grief, a guest post by Hannah Barnaby

Today I’m honored to share with you a moving post by my former coworker and fellow Simmons College alum, Hannah Barnaby. I recently reviewed Hannah’s newest book, Some of the Parts, here on TLT. In my review, I wrote, “Barnaby’s novel is a devastating and powerful look at grief, guilt, and how to survive the aftermath of something that changes who you are. A must-read.” Hannah’s post today on grief is a fantastic contribution to our ongoing series on Mental Health in YA Lit. Visit the #MHYALit hub page to see all of the posts.

I have experienced—fought, wrestled with, submitted to, overcome—both grief and clinical depression. But I have only written about one.

The protagonist of my young adult novel, Some of the Parts, is in the throes of grieving for her older brother. Tallie lost Nate a few months before the book opens, in a car accident for which she feels entirely responsible, and she wears her guilt like a lead necklace. She can’t let go. She doesn’t think she deserves to. And then she finds out that she might not have to—Nate was an organ donor, and one of his recipients reaches out to Tallie’s parents. Suddenly Tallie sees a way to alleviate her sadness: if she can track down the other organ recipients, she can prove to herself that Nate isn’t truly gone.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Is this rational? No. But neither is grief. And neither is depression.

My first bout with depression was during my senior year in high school. My parents were getting divorced and I was overwhelmed with plans for college and homework and extra-curricular stuff. About halfway through the year, I felt myself shutting down. I came home from school every day and got in bed. I slept until dinner, did my homework in a zombie state, and went back to sleep. This went on for weeks. Finally, my parents found me a therapist. Seeing her twice a week until the end of the school year was . . . well, frankly, it was a pain in the butt. I was tired of talking about myself and I was sure that my fatigue and sadness would pass on their own. I told myself—and my therapist—that I was just sad about my parents splitting up. “That’s not what this is,” she told me. And she was right.

Clinically speaking, depression and grief look a lot alike. Both involve many of the same symptoms: sadness, fatigue, changes in appetite and sleep patterns, poor concentration, guilt, hopelessness, unbidden memories. Martha Clark Scala, a psychotherapist in San Francisco, says, “Among the bereaved, these symptoms are usually mild or temporary. But these same symptoms may be more chronic or severe among those who are clinically depressed.” Scala also identifies some additional symptoms that may be signs of clinical depression rather than—or on top of—grief: worthlessness, exaggerated guilt, suicidal thoughts or plans, powerlessness, low self-esteem, agitation, and loss of interest in pleasurable activities.

I can attest to the fact that it can be difficult to tell grief and depression apart. I did eventually emerge from my high school depression, but it found me again in college. And again after graduation. It kept coming back, like a slow tide, and I learned to recognize it and how to ask for help when I needed it. But then something terrible happened.

In 1999, I was a graduate student at Simmons College in Boston. I had just started my second semester and I was given a part-time work study job to help with expenses. I was at that job—stuffing social work school applications into envelopes—when the phone rang at the desk where I was sitting. It wasn’t my desk. It wasn’t my phone. But the call was for me. It was my father, calling to tell me that my younger brother Jesse had died the night before, in a fire at his fraternity house.

What followed, as you can imagine, was a whirling blur of confusion and sadness and difficult things. And as my grief soaked into me, I thought, “Oh, I know what this is. I recognize this.” It felt just like my senior year in high school, my sophomore year in college, my post-college year. I was almost relieved, because I knew what to expect. There had always been an ebb and flow to my depression and so I waited for it to move. But it didn’t. Because this wasn’t depression at all, and it wasn’t until I named it something else that I understood: I would have to find a whole new way to cope with this. It was grief, and it had its own landscape altogether.

Eventually, I was able to go back to school and to work, and I felt the weight of my grief lessening as I moved forward. Depression had never been like that. Depression had followed its own calendar and it had never dissipated until it was good and ready, no matter what I was doing from day to day, and I think that was because it had no source the way grief did. My depression was like a cloud of gnats that appeared and disappeared with little warning; my grief, though, was born of one very specific loss. And in a strange way, I found that comforting.

In writing Tallie’s story, I came full circle in my own grief. I revisited every part of the emotional journey I took after my brother died and I dragged Tallie through it, too. Part of me felt terrible, doing that to someone else. (Even a fictional someone.) But the rest of me felt sure and strong, because I could tell her with certainty, “There is an end to this. There is a door ahead of us. We’ll walk through it together, and you’ll see—there is hope on the other side.”

Meet Hannah Barnaby

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Hannah Barnaby is a former children’s book editor and bookseller, and was the inaugural children’s writer-in-residence at the Boston Public Library. Her debut novel, Wonder Show, was a Morris Award finalist in 2013. She lives in Charlottesville, VA with her family. You can find her online at www.hannahbarnaby.com and follow her on Twitter @hannahrbarnaby.

Hannah Barnaby is a former children’s book editor and bookseller, and was the inaugural children’s writer-in-residence at the Boston Public Library. Her debut novel, Wonder Show, was a Morris Award finalist in 2013. She lives in Charlottesville, VA with her family. You can find her online at www.hannahbarnaby.com and follow her on Twitter @hannahrbarnaby.

About Some of the Parts

For months, Tallie McGovern has been coping with the death of her older brother the only way she knows how: by smiling bravely and pretending that she’s okay. She’s managed to fool her friends, her parents, and her teachers, yet she can’t even say his name out loud: “N—” is as far as she can go. Then Tallie comes across a letter in the mail, and it only takes two words to crack the careful façade she’s built up:

For months, Tallie McGovern has been coping with the death of her older brother the only way she knows how: by smiling bravely and pretending that she’s okay. She’s managed to fool her friends, her parents, and her teachers, yet she can’t even say his name out loud: “N—” is as far as she can go. Then Tallie comes across a letter in the mail, and it only takes two words to crack the careful façade she’s built up:

ORGAN DONOR.

Two words that had apparently been checked off on her brother’s driver’s license; two words that her parents knew about—and never revealed to her. All at once, everything Tallie thought she understood about her brother’s death feels like a lie. And although a part of her knows he’s gone forever, another part of her wonders if finding the letter might be a sign. That if she can just track down the people on the other end of those two words, it might somehow bring him back.

Hannah Barnaby’s deeply moving novel asks questions there are no easy answers to as it follows a family struggling to pick up the pieces, and a girl determined to find the brother she wasn’t ready to let go of.

Filed under: #MHYALit

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT

A powerful post. I lost my brother while I was in the midst of a bout with clinical anxiety. At first my anxiety actually seemed to lesson, in a strange way my brain was comforted by having something real and concrete to be distressed about as opposed to the random feeling of fear. But after the grief started to become slightly more manageable the anxiety was waiting. They definitely interlock in my life but they are their own beasts.