This Above All, a guest post by M. E. Corey

My mission is to create stories that teens can see themselves in and be entertained by so I can help them find a way through life despite what may have happened to them so far.

I grew up in a time before the great Young Adult Literature Renaissance of the late 1990s and early 2000s. While many critics and bibliophiles believe this surge of creativity in YA books occurred in the 70s, or even the 60s, I’m here to say that looking for books to read in the late 80s when I was a teen led me to a scant number of titles I found interesting.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

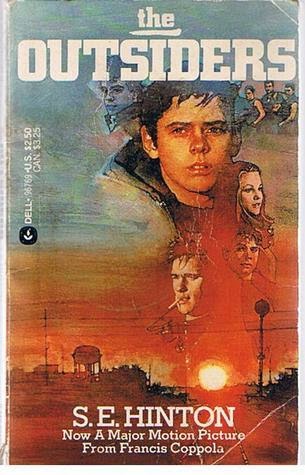

One of my biggest life-changing moments wasn’t even my moment: My brother got to read The Outsiders by S. E. Hinton (1967) when he was in middle school, but my class didn’t. When the movie came out in 1983, I tagged along to see it with him.

A paperback copy of the book was in my hands days later. On the cover a faux painting depicted Ponyboy with Cherry Valance and Randy, Dallas Winston and Sodapop fading into a beautiful sunset. S. E. Hinton’s name was in 24-point font at the bottom. My twelve-year-old self was deeply impressed with her success. She’d written this when she was just a little older than I was. But most importantly, she’d written a book that I would reread more frequently than any other. Ponyboy was me—a sensitive boy who wasn’t understood by his family or friends, who was teased for being himself, who was bullied by other kids.

Ponyboy’s social status resonated with me. I had always felt like an outsider, and this book made that an okay thing to be. Ponyboy wasn’t awkward or dorky; he was cool. The Outsiders and my search for other books like it spawned the author in me. There were no other books like it in 1983. There were others by S. E. Hinton, and I read them all, but none of them had the same confirmation of my ostracized and wounded self.

Without other texts to validate me, I began writing my own. For all of junior high and high school, I spent summers at the desk in my room, handwriting the words of my own Outsiders tale. Only, The Outsiders wasn’t my story to tell. I hadn’t been jumped by socs or helped my best friend escape murder charges. I hadn’t lost my parents in a car accident.

Not until I finished college did I complete a full draft of that book. By then, my main character was a popular football player in love with an older woman. The story resembled The Great Gatsby more than The Outsiders, but, of course, The Great Gatsby wasn’t my story to tell either.

Maybe my confused, rocky start to novel writing makes sense based on my rocky start to humanhood. Knowing who I am inside but not being able to express it outside leads not to confusion but to frustration. I was confused about why I was who I was, but never about who I was. I think in that way I was lucky. It takes some people decades to figure themselves out.

The concept of knowing who you are is one that philosophers return to over and over. Aristotle said, “Knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom.” Though I respect Aristotle, Socrates said something more profound about identity: “To find yourself, think for yourself.” While it’s wonderful to say you know who you are, where do you start when you don’t know? Socrates’s words may or may not have inspired Shakespeare to write certain segments of Hamlet, such as Polonius’s speech to Laertes when he says, “This above all, to thine own self be true.” Being honest with yourself about who you are is at the root of all relationships, not only the relationship you have with yourself. It helps you choose the right friends, the right career, the right partner.

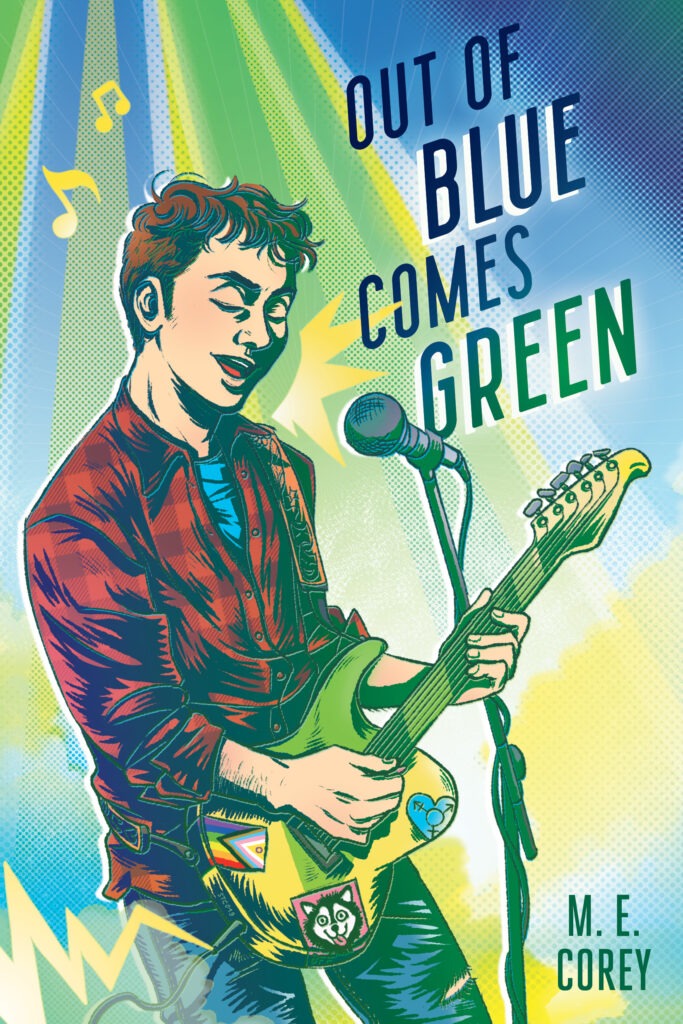

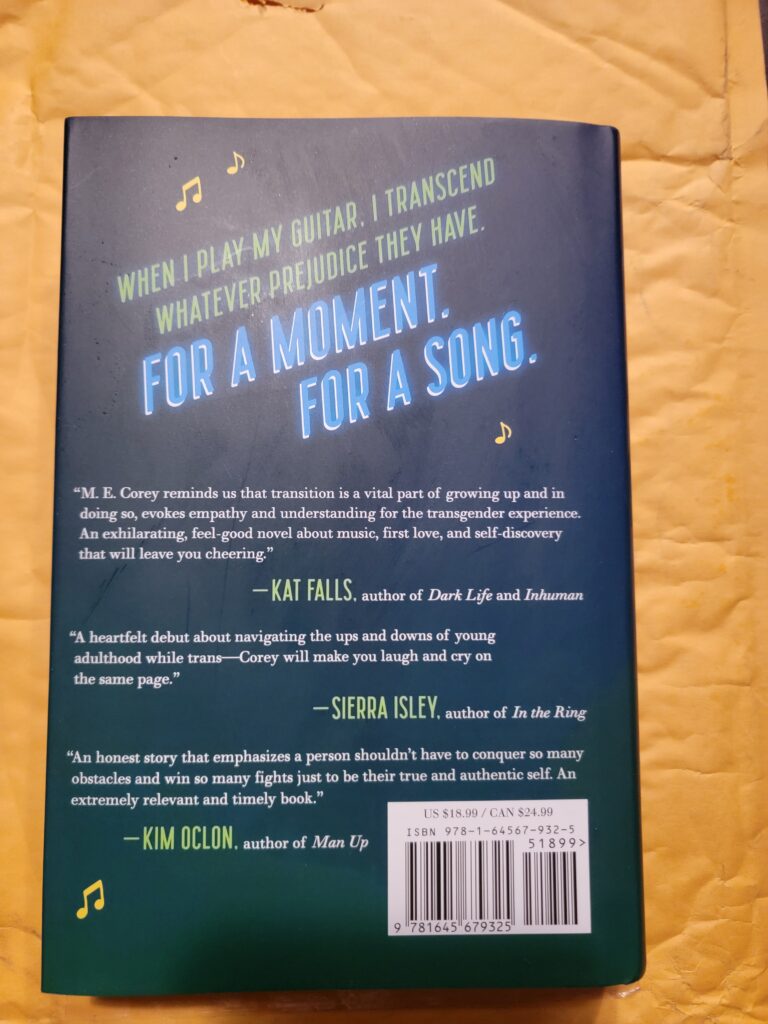

My main character Nate Kinkade has no confusion about who he is. He’s a boy who loves music and dogs. Just because everyone else doesn’t recognize him as such does not make it any less true. Those around him may struggle with his identity, making his suffering over his gender part of their experience or even a threat to their rights. But for Nate, it’s a non-issue. Nate simply wants to be the gender he knows he is.

In unfortunate ways, Nate resembles Victor Frankenstein’s creature, a character I still identify with because of his continual rejection by humankind. The creature is my college-level Ponyboy Curtis, if you will. Though not grotesque or completely cast out, Nate receives judgment from society—he is an interloper, an intruder, someone who doesn’t belong with the “regular people.” The creature is all of these things as well, which chapter fourteen shows brilliantly when he bonds with the old blind Mr. DeLacey only to be chased out and beaten by sighted Felix who fears for his father’s life. Still, after that massive rejection, the creature longs to be given a chance to explain himself. He knows visually he’s hideous, knows he isn’t like other people, yet in his mind, he sees himself as benevolent. As someone with friendship to offer.

The desire for acceptance and belonging is fundamental to being human. Early in my life, grade school children taught me that I didn’t fit in. I was an outsider despite anything I might have to offer. Nate Kinkade is given this message, too, and he’s able to overcome it. His friends and his inner strength bolster him against ignorance, prejudice, and cruelty, enabling him to become his true self and share his music with others.

Meet the author

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

M. E. Corey is a guitar player, high school teacher, and adolescence-trauma survivor. Writing has always been his outlet to cope with feeling like an outsider. When he isn’t teaching or writing, he travels, walks his rescue dogs, and hangs out with the love of his life with whom he’s raising a super cool kid. He lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Instagram: @matthew.corey1

Instagram publisher: @pagestreetya

Facebook: matthew.corey1

Twitter/X: @mrmattcorey

Website (in progress but on the internet): mecorey.com

About Out of Blue Comes Green

Kinkade wants what every other teenage boy wants: a girlfriend and a successful rock band but that’s not as easy as it sounds.

After a killer school talent show performance in full masculine presentation, trans boy Kinkade is quickly knocked back down to earth when his crush rejects him, and the whole school sees him in the dress his mother forced him to wear for a family photo. So, when the new girl Madi assumes he is cis and asks him out, he accepts without correcting her.

After years of being ignored by his old crush and bullied by other boys, Kinkade just wants to convince Madi that he’s a regular guy’s guy. To impress her and finally win the approval of his peers, Kinkade agrees to his best friend Libby’s suggestion that they enter a competition to become the band for prom despite his misgivings.

In between band practice, weightlifting, and dates, Kinkade accidentally becomes an animal shelter volunteer under an assumed name—and it’s there among the unconditional acceptance of dogs that he finally receives the affirmation he’s been longing for.

But it’s going to be harder than he thought to play the show, get the girl, and become the man he’s meant to be.

ISBN-13: 9781645679325

Publisher: Page Street Publishing

Publication date: 04/23/2024

Age Range: 14 – 17 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Endangered Series #30: Nancy Drew

Research and Wishes: A Q&A with Nedda Lewers About Daughters of the Lamp

Preview: Archie Jumbo Comics Digest #350

ADVERTISEMENT