The Stories We Tell About Mental Health and Why, or #BooksReallySaveLives, a guest post by Ann Jacobus

Stories are how we all make sense of the world. We tell them to ourselves and others, to entertain, yes, but to learn and understand, to reassure, and to heal. My mom, however, used “story” as a euphemism for a fib when I was little. “Are you telling a story?” she’d ask, when I was. Then I grew up to be a fiction writer. As Neil Gaiman said, “We who make stories know that we tell lies for a living. But they are good lies that say true things, and we owe it to our readers to build them as best we can.”

I write for young adults generally around mental health themes, having struggled with depression and suicidality in my teens. Helping to change the large story of mental illness is one of my passions. As a teen librarian, I suspect the mental health of this age group is of concern to you too.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I’ve got good news and bad news.

First the bad news. Mental health issues, and worse, mental health crises, among the young are up at unprecedented levels. The CDC just released distressing numbers from their broad Youth Risk Survey: 30% of US high school girls contemplated suicide in 2021, a 60% increase from a decade earlier. “Female students and LGBQT students are experiencing alarming rates of violence, poor mental health, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors,” they said.

According to the National Alliance for Mental Illness (NAMI), in 2020 17% of youth (ages 6-17) experienced a mental health disorder. Many more young people were impacted by the 21% (1 in 5) of adults—parents and care-givers—who experienced mental illness during the same time. Mental illness is fatal when lives are lost to suicide, eating disorders, and substance abuse disorders.

There are a lot of things to blame—the pandemic and misuse of social media are two of my favorites. But we’ll focus on what we can do about it.

The good news is twofold: First, we’re all talking about mental health a lot more as a result of these crises, and many public figures are opening up about their and their loved ones’ experiences. Stigma is about our biggest barrier to helping people of any age who are battling mental illness. We can’t fix it if we can’t talk about it.

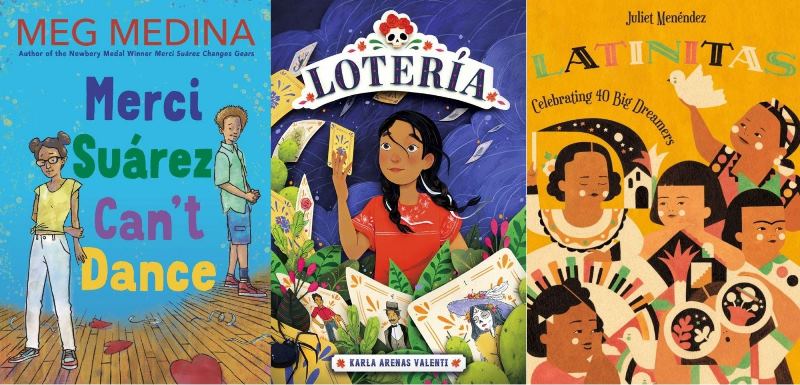

Second, and best of all, in the last decade or so, hundreds of fiction books for young readers have come out from almost all publishers that deal with any and all elements of mental health.* And more are coming. But you know this, and the fact that very few societal ills cannot be improved tremendously, or even eradicated, by books.

More and more writers want to change society’s story of mental illness, by writing about characters who want the same things all characters want—acceptance, friends, family, love, achievement—but also by writing honestly about mental health issues the character(s) have to deal with in their family or themselves. Like so many of us do.

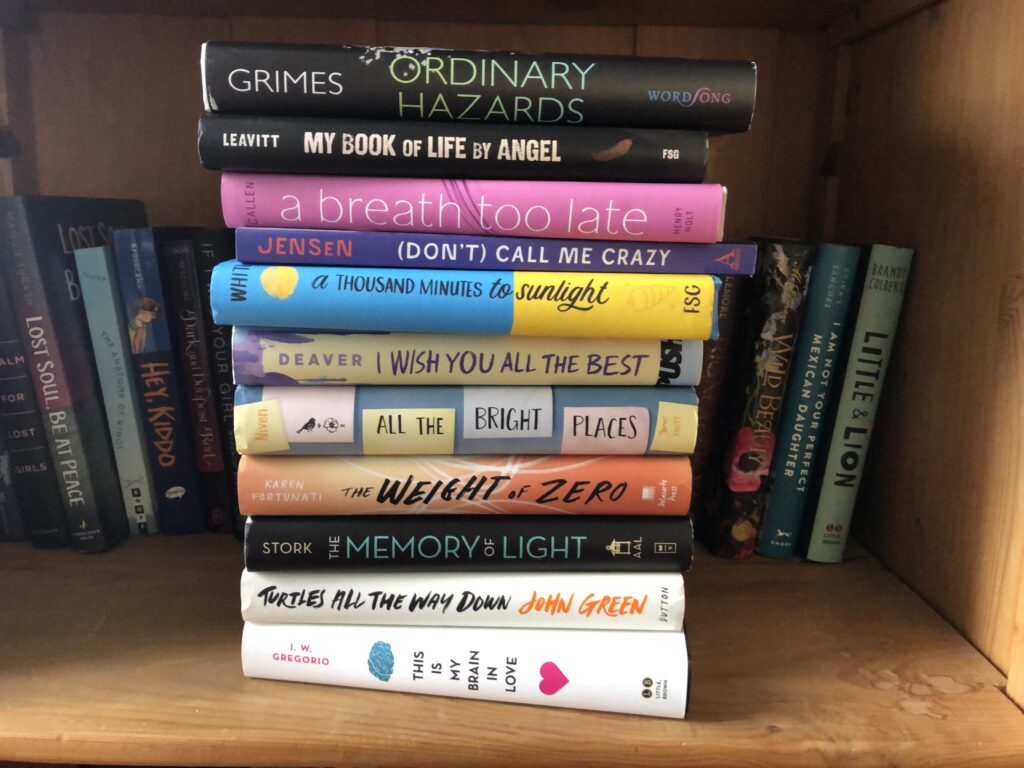

Author and psychologist Nancy Bo Flood and I try to keep a running list of books for children and young adults that deal well with mental illness, i.e. that are not just honest but accurate about the diagnoses and challenges; that avoid tropes and stereotypes; that model supportive family members, community and/or professionals; that model characters coping; and that are ultimately hopeful. The outstanding books on our list, to name but a few, include picture books by the likes of Dan Santat and Shaun Tan, middle grade novels by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley and Tae Keller; and YA by John Corey Whaley, Meredith Russo, Laurie Halse Anderson, Brandy Colbert, Neal Schusterman, Martine Leavitt, and Francisco Stork.

When younger readers can read about families or about other kids who suffer from things they have been grappling with in secret and often shame, it can enable them to break their silence, to reach out, and to ask for help. Lifesaving help.

There’s another imperative aspect of this topic to cover: the rates of poor mental health in communities of color and among those who identify as LGBTQ. Black, Hispanic, and Asian communities generally report more stigma around getting help for mental illness, and often have higher rates of illness and lower access to resources and treatment. LGBTQ youth are four times more likely overall to attempt suicide than others teens, and trans youth, nine times more likely. These kids critically need stories that validate who they are, how they’re feeling, and that they are not alone. Outstanding authors who include mental health issues in stories centered in these communities include many of the aforementioned, along with Kacen Callender, Anna-Maria McLemore, Kelly Loy Gilbert, Stephanie Kuehn, Joanna Ho, Patricia Park, Nikki Grimes, and Adib Khorram, again to name but a few.

Younger kids from all backgrounds can read about a character dealing with a mentally ill or a substance abusing family member, for example, or about kids themselves coping with anxiety or obsessive-compulsive disorder. Teens can read about other teens or their family members suffering not just from depression, but from illnesses such as schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or eating disorders, as well as about hospitalization, and the mental-health-crushing effects of trauma and abuse. Initially, stories often revolved around the mental illness, but increasingly it’s just one of a character’s many obstacles, or a managed part of their life ancillary to their story goal. As in real life, there are a huge variety of experiences and outcomes and the literature increasingly reflects this.

Dr. Flood and I try to offer guidance to writers on including mental illness in books for younger readers, as we believe it requires special responsibility. So many tropes and damaging stereotypes need to be eradicated, such as that someone can just “get over it.” We’re talking about illness. We wouldn’t say to someone with diabetes, “just get over it.” Or the dangerous trope that people suffering mental illness are violent. Absolutely not. However, hateful, violent people are sometimes mentally ill.

Writers are reframing mental illness not as something secret and shameful, and for which there’s little or no help or hope, but as a normal part of life with many options for healing and learning to cope. Just as there are for physical health. Is that a “story?” This scenario is certainly true for growing numbers of young people, but we all know how many real-life situations don’t live up to these ideals. Far too many sufferers live in shame and silence with little or no access to help and resources. But by modeling a more ideal situation to young readers—who are the future after all—may it become self-fulfilling.

Neil Gaiman emphasized building stories as best we can, “…because somewhere out there is someone who needs that story. Someone who will grow up with a different landscape, who without that story will be a different person. And who with that story may have hope, or wisdom, or kindness, or comfort. And that is why we write.” Children and teens who struggle with mental health issues badly need to know how they and/or their loved ones fit into the world. Books that “mirror” and “window” mental illness honestly, but as normal and manageable, can not only show us all an inclusive, affirmative, and optimal future, they will save lives.

Footnote:

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

*Stories about teens have always had mental health issues lurking in them, we just avoided identifying it as such. In the 60’s and 70’s any number of books for younger readers touched on depression and suicide. Don’t forget, Pony Boy committed “suicide by cop” in S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders. In 1986 Author Richard Peck was one of the first to include a depressed young character who completed suicide in his book, Remembering the Good Times. Sharon Draper took trauma, depression, and suicide head-on in 1994 in Tears of a Tiger. Then Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher in 2007 arguably opened the floodgates.

Meet the author

Ann Jacobus earned an MFA in Writing For Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts and is the author of YA novels THE COLDEST WINTER I EVER SPENT, and ROMANCING THE DARK IN THE CITY OF LIGHT. A former suicide crisis-line counselor, she’s a mental health advocate and speaks to high school students about writing and suicide prevention at the same time.

Website: www.annjacobus.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/annjacobus.author

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/annjacobus/

and Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/annjacobussf/

About The Coldest Winter I Ever Spent

Eighteen-year-old Del is in a healthier place than she was a year and a half ago: She’s sober, getting treatment for her depression and anxiety, and volunteering at a suicide-prevention hotline. Her own suicide attempt is in the past, and living in San Francisco with her beloved aunt has helped her see a future for herself.

But when Aunt Fran is diagnosed with terminal cancer, Del’s equilibrium is shattered. She’s dedicated herself to saving every life she can, but she can’t save Fran. All she can do is help care for her aunt and try to prepare herself for the inevitable—while also dealing with a crush, her looming first semester at college, and her shifts at the crisis line.

After Aunt Fran asks for her help with a mind-boggling final request, Del must confront her own demons and rethink everything she thought she knew about life and death.

ISBN-13: 9781728423951

Publisher: Lerner Publishing Group

Publication date: 03/07/2023

Age Range: 13 +

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on BlueSky at @amandamacgregor.bsky.social.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The 2025 Children’s Lit Animal Rankings

Review of the Day: Fireworks by Matthew Burgess, ill. Cátia Chien

Cat Man | Review

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

ADVERTISEMENT