Things I Never Learned in Library School: You Won’t Get Paid to Read and You Will Never Read Everything in Your Library Collection (See Also: Why we can’t pre-read the books that we purchase, even while facing massive book bans)

For some background, I have now been a public librarian for almost 30 years. I have worked in small, medium and large sized libraries. I have bought books for small, medium and large sized collections every single one of those years. In addition, I created and run this blog. Because of this blog, my co-bloggers and I often receive Advanced Readers Copies (ARCs) of books. We get a small number of titles every year, but nowhere near the number of titles that are published each year. I share this with you to set the stage.

As you may be aware, there are groups of people pushing for widespread censorship and book banning in our libraries. Though they are often focused primarily on public school libraries, public libraries are sometimes targeted as well. One of the continually proposed possible resolutions to this problem is to have librarians read every book before they purchase it for a library. Today, I am here to tell you why that is not possible in any way, shape or form.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

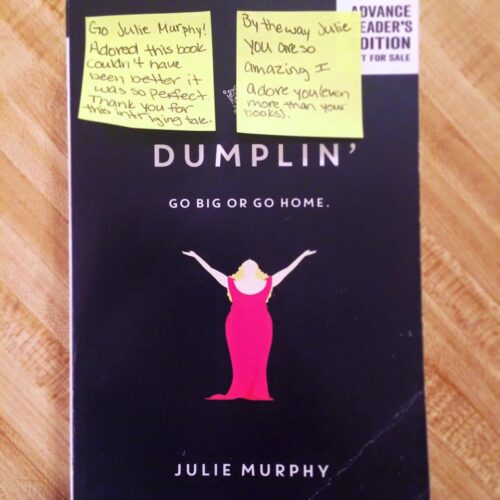

The Cost of ARCs

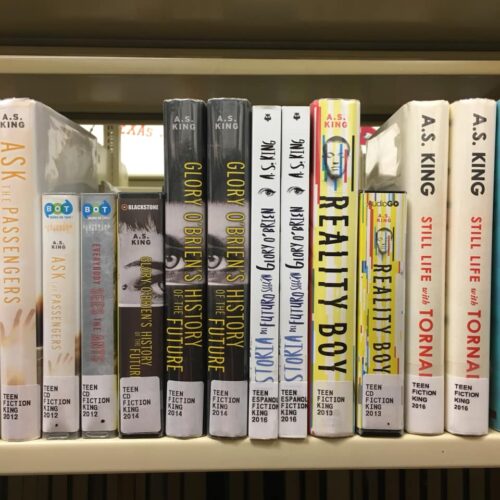

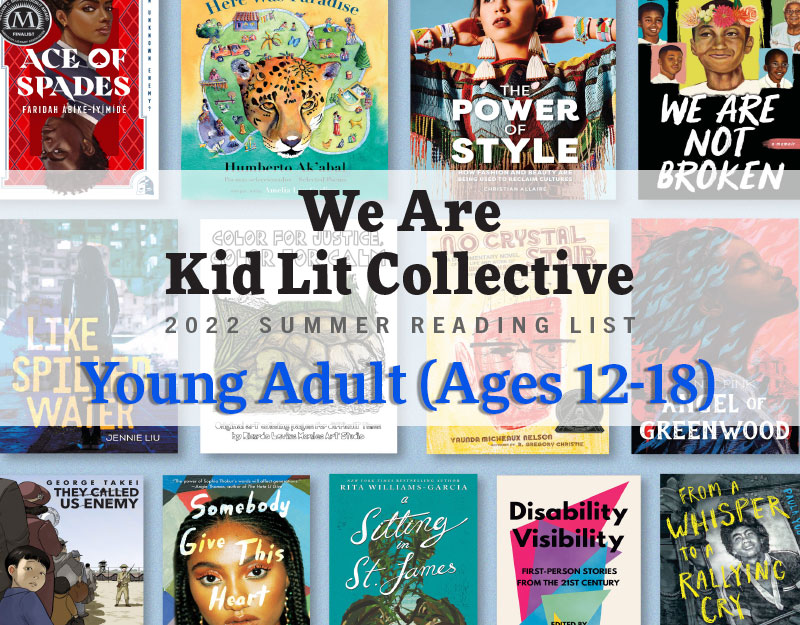

Thought ARCs sometimes do exist for books, they do not exist for all published works. To give you just a glimpse, a recent analysis of JUST YA (young adult or teen fiction) titles revealed that as of April of 2022, there were 622 titles on the calendar to be published. Previous years reveal upwards of 900 YA titles. These are usually first run, hardback copies of YA titles. And they are almost always fiction. It doesn’t include the nonfiction, the various high/low titles published by publishers like Orca, trade paperback reprints, etc. There are literally 1,000s of YA titles alone that a YA librarian has to wade through to select them for their library. Even in the years when I have gone to ALA, TLA and received boxes of ARCs at my home, I have never gotten more than around 100 ARCs. A small fraction of the number of titles released that year.

Each ARC has a high price for the publisher, which is part of the reason why they are in limited supply. There is the printing cost, the mailing cost, and when distributed at large library conventions, the cost to pay to exhibit and send staff. In addition, they are not final copies, so there are often small and sometimes big changes in between the printing of an ARC and publication of a final version. In comparison, there are more than 17,000 public libraries in the United States. There are around 13,800 public school districts. You are looking at the need to produce more than 20,000 ARCs for every title published for youth, and from birth to age 18 that number is in the thousands.

So, hurdle one: there is a high cost to ARC creation and distribution

Librarians Don’t Actually Get Paid to Read

In the 30 years I have been working as a public librarian, I have gotten paid to read on the job almost zero hours. While at work, I crunch data, order books and more. At some times in my career I have ordered books AND done all the programming AND worked the public service desk AND served on committees, etc. In a 40 hour work week, there is not time allotted for being paid to read. There is always the expectation that you do read, and on your own time, but there is no time built into the day to accomplish this task and no financial compensation for doing so.

The only exception I have ever found to this rule has been children’s librarians preparing for storytime. I do not begrudge them that at all, I am just trying to be as thorough as possible in my discussion here. Part of the reason this can happen is because picture books are vastly shorter and you can read through numbers of them while on the clock. When I did storytimes, I could read through a number of picture books before I could even get through the first chapter of the most recent YA novel (for the record, this is hyperbole designed to make a point). The difference in time investment is really important when we talk about being paid to preview read a book. On the flip side, in my 30 years I have gotten very few ARCs of picture books. I am sure part of the reason is because of my area of focus. But even when I have purchased for all youth ages, I still get vastly more Middle Grade and YA ARCs than picture book ARCs. I have just never seen ARC distribution for picture books the way that I have for books for middle grade and young adult readers.

So, hurdles two and three: ARCs aren’t readily available for all formats to all librarians and librarians don’t actually get paid to read

So, Do Librarians Read at All?

The correct answer is: some do, and most often they do so on their own time. The most I have ever read is between 200 and 300 Middle Grade and YA books a year. So you’re looking at between the 2 categories about 15% of the total number of titles published. And that’s a good year. I have had years where I have barely read more than 100. Almost all of this reading occurs on my own time. And let’s say it takes me an average of 5 hours to read a book. You’re looking at 2,500 hours for those high reading years. I only work around 2,080 hours a year.

In an average year, I will buy around 400 YA novels for a library, depending on which library and their size and budget. So that would be about 2,000 hours of my 2,080 year spent reading on the clock just to purchase those books. That doesn’t include the books that I may read and decide not to purchase for whatever reason. So, if I had to read each and every book before I purchased it, which would mean basically every minute of every day I was at work would need to be spent reading books. As you can see, this is physically, philosophically and financially impossible. I have never gotten paid to read even a little, I’m certainly not getting paid to do nothing but read.

Side note: the conversation of whether or not librarians SHOULD get paid to read is a whole other issue, and the answer is yes, they should. But again, that is not the focus of this post.

One of the ways that librarians solve the above hurdles is by crowdsourcing reviews using professional journals. So let’s discuss.

A Brief Discussion of Professional Reviews

To overcome this hurdle, ARCs are sent to professional journals for review. Professional journals have a small staff of – often volunteer – reviewers who do this work. I was a professional reviewer for VOYA from about 2001 to -2014. In order to do this work I had to apply. After being selected, I was assigned one book a month and had to submit a review following a very rigid format with outlined criteria and it was edited for brevity by the review editor.

I no longer review for VOYA but I do review books here at Teen Librarian Toolbox, which is a part of the School Library Journal blog network. My co-blogger, Amanda MacGregor, reviews books here and for SLJ the actual journal. Reviewing books here at the blog allows us both to have a bit more freedom in what we say, the number of words we take to say that, etc. But this blog is not considered a professional review journal; Amanda’s reviews for SLJ are given more weight for most libraries than her blog reviews are, for example.

There are a variety of professional journals that organize and publish reviews from a group of cultivated and trained reviewers. Libraries use these resources to help them make book purchasing decisions. Librarians pour through these journals reading reviews and we use vendor resources – think Amazon, but for libraries – who often put all the reviews into one space for us. These reviews help inform purchasing decisions, but they are not the only information we look at.

What, Besides Reviews, Helps Informs Book Purchasing in Libraries?

When I am ordering books, I usually have no less than 5 spreadsheets open on my computer to help me make informed decisions about library purchasing. These spreadsheets include things like budgets, higher circulating areas, allotted space, and more. There is far more math and data analysis than most people realize in collection development in public libraries.

In addition, I usually consult my library catalog and other statistical information. We are looking for authors that circulate, categories that circulate as well as places where we have gaps (not enough titles or information) and more. Collection Development and book ordering is actually a pretty complex and deeply informed process. It involves a lot of data. And combing through a lot of reviews.

The professional reviews are important because they help us crowdsource a time consuming part of buying books. It is literally impossible in every way for librarians to pre-read every single book that they purchase. Purchasing decisions are not made on a whim. We are trying to make informed decisions for large and diverse public populations that meet not just the needs of the majority, but also include the needs of marginalized groups as well. It’s a thoughtful, time consuming process done with intention and attention to detail.

Is this process perfect? No. But it is a well-developed and sustainable model that has been working for all 30 years that I have been buying books for libraries and long before me. It is important to note that it is a realistic, sustainable model that has been working for decades.

The Biggest Hurdle: When Talking About Content, You Can’t Escape the Problem of Subjectivity

The problem isn’t actually about whether or not librarians can or should pre-read every book before it goes into the library. We can’t. The problem is actually that we don’t all agree on what is or isn’t appropriate for every kid. That’s because every kid is different, as is every family, and it’s all subjective.

A personal example. The other day I made a comment to a friend about the current book banning issue and she replied, “But we all agree that there should be no sexual information in a book for kids.” To which I replied, “We don’t actually.” You see, I, the parent of two children, have always been very scientifically oriented and want my children to have true and accurate information about the world, including how their bodies work. The reproductive system is just a system in the body like the circulatory system, the nervous system, or the respiratory system. In addition, I am the mother of two daughters who have or will start puberty as some point long before they are technically adults and I believe that they deserve to know what that means. Puberty also includes big feelings that can be hard to understand and navigate and books can help them process those feelings in safer ways than say, having unprotected sex in the back seat of a car because you don’t fully understand what is happening, how you’re feeling, and what steps you can take to keep yourself safe from STDs and pregnancy should you choose to be sexually active. And finally, research has shown that talking with kids about sex can help prevent sexual abuse as kids know what consent is, what abuse can look like, etc. So no, we don’t all agree that there should be no discussion of sex in books for children, nonfiction or fiction. That is why libraries purchase such a wide variety of books. Not every book is right for you, and that’s okay, because it is right for others.

That is also why public libraries encourage parents to be involved in their child’s use of the library. There was a period of time where I banned the show Spongebob in my house because I did not like the way the characters talked to one another and found it to be kind of cruel. I did not go on a crusade to ban the show, I simple talked to my kids about why I was banning the show, gave them other viewing choices, and parented my kids. Public libraries give parents the space and resources for each and every family to successfully parent their families and allow others to do the same.

Book banners want to go beyond parenting their own children to parenting all children. Their goal is to take away my parenting rights by overriding my personal belief system with theirs. I believe in teaching my kids true and accurate history and health education. Once outside forces begin banning those books, they are no longer expressing their parental rights, they are denying me mine.

Another personal example. I first read the book It by Stephen King in the 6th grade. I have read it no less than 5 more times in my life. One day, a friend emailed me and said her teen, a 7th grader, wanted to read it but she didn’t want them to because of a scene involving sexual abuse and could I recommend something different but along the same lines. I had read the book 5 times throughout my life and was flummoxed by what she was mentioning as her concern. When I read it, that didn’t stand out to me in any way.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

This is not the only time this has happened. Sometimes a parent mentions a brief curse word in a book that I’ve read that I never noticed. Sometimes a parent is upset at even the implication of a crush or a simple kiss. I have had parents complain about pictures of parents with tattoos in a picture book to me, a parent with a tattoo. I have had parents complain about the nudity in a book about Nazi concentration camps but not the pile of dead bodies. The truth is, you can never tell what someone is going to object to in a book.

This point matters because even if we pre-read every single book before putting it into our libraries, we are not all looking for or offended by the same things. The answer to this problem has always been and still is that at the end of the day, parents concerned with content should use the library with their children, research titles, or pre-read titles before allowing their children to read them.

So, Why Do We Even Have Librarians?

I have spent 30 years of my life now becoming an authority on youth literature and public library services. In the process I have taken classes on adolescent development, literature, programming, data analysis and more. I have read over 10,000 kidlit books for youth of all ages. I have put together and hosted a minimum of 1,500 programs. I have spent around 50,000 hours working with, talking to, and serving youth in public libraries. I have worked with kids through their middle school and high school years, sending them off to college and watching them come back and start their own families. I have knowledge and a skill set that I have worked hard to cultivate. And I use that not only to serve the public today, but to help train and educate the next generations of public library employees. And the cycle continues. There is something to be said for expertise, knowledge gained both in education and on the job, and how it helps promote success for the community.

As a parent, I fully understand that we don’t all agree on what we want raising our kids to look like. Remember, I’m the parent who banned Spongebob in their home. I completely understand that we are in a place in our culture where we are having huge disagreements on a systemic level about what is right for kids. Which kids is an entirely different and important question, but not the point of this particular post. But I am here to tell you that the solution is not to require librarians to read every book before it’s purchased. It’s not in any way sustainable and the truth is, what we have been doing for decades works, it just requires parents to be involved with their own kids library use and to give other parents the freedom to do the same.

Filed under: Collection Development, Things I Never Learned in Library School

About Karen Jensen, MLS

Karen Jensen has been a Teen Services Librarian for almost 30 years. She created TLT in 2011 and is the co-editor of The Whole Library Handbook: Teen Services with Heather Booth (ALA Editions, 2014).

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Moral Dilemma of THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

This is just my opinion regarding the currant book banning craze. I do not believe the people and politicians using this subject to take a “stand” on, have ever read the books they are trying to ban. I base this on things said about certain books (repeated talking points) that are not in the book under fire. This one says this book should be banned because. . . Another picks up that thread, adds to it and the next thing you know an elected representative of the USA is ranting in prime time,about a book they have never read and quoting a scene from the book that is not even in it. Perhaps the book banners should be required to read and do an oral Q&A about the book. That might put them on an actual problem to spend their time on.