Writing Whiteness, a guest post by Kate Hattemer

In a racial justice training I did at the school where I teach, the facilitator asked us to cast our minds back to our early understandings of race. It made me think. I’m a white woman, and despite attending an elementary school that was majority Black, I grew up barely cognizant of my whiteness. I remember being reprimanded for announcing, “I’m not wearing no coat” — that was not how we spoke — and I remember noticing that my honors classes in high school were almost all white, counter to the demographics of the school. That’s about it.

Yet from an early age, I was aware I was a girl and I would be treated differently because I was a girl. I remember a kindergarten classmate shoving me up against a door to kiss me. I remember noticing that the lists of presidents and astronauts and scientists in my children’s encyclopedia were all men. In high school, when I fell deep into the world of competitive trivia games, I remember my teachers and coaches casually posing theories as to why girls weren’t fast on the buzzer. (I was fast on the buzzer.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I have a lot of childhood memories of being oppressed. I don’t remember so well the experience of being on top.

This is common, I think, and understandable. In a weird way, it can be a whole lot more comfortable to examine ways you’ve been hurt by oppressive systems than to reckon with the ways you’ve been complicit, and perhaps still are complicit, with systems that hurt others. My whiteness informed every day of my childhood — the way I was treated by teachers and shopkeepers and passersby, the places we lived, the jobs my parents had, and on, and on, and on, in many ways I’m sure I don’t know — yet I barely knew I was white. I was just, you know. The default. Not black, not brown. I knew I was Swiss. Did that count?

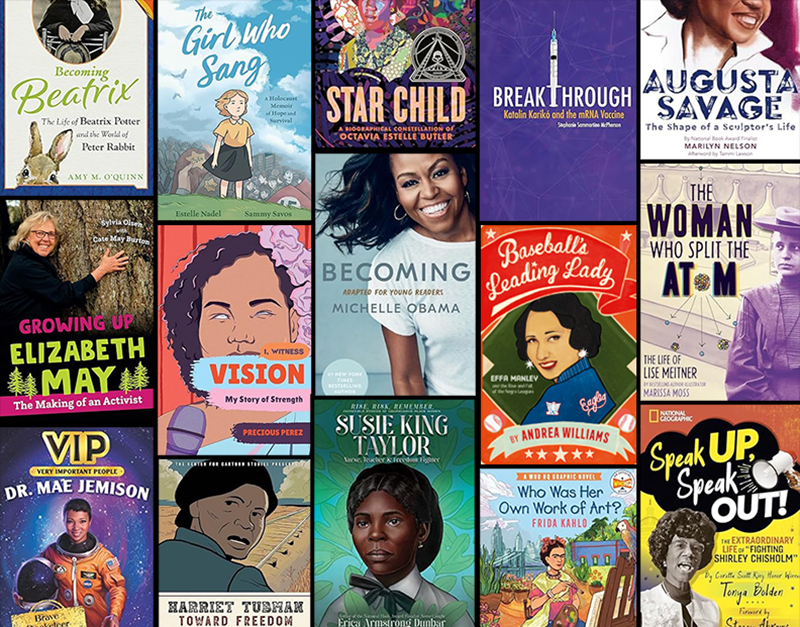

Unsurprisingly, this discomfort is mirrored in children’s literature. In the past few years, as white authors have felt the need (from both the industry and our own consciences) to diversify our books, I’ve seen — and, yes, I’ve written — a familiar pattern. There’s a white protagonist (WP) who has at least one friend of color (FOC). Maybe WP visits the FOC’s house and eats some authentic kimchi or tacos, or maybe WP notes that FOC has a different hair-care routine. Or maybe WP witnesses a microaggression visited upon the FOC; the WP doesn’t understand at first, but the FOC explains, and the WP comes to a greater understanding of what it’s like for the FOC to move through the world.

I’m not saying this is a problem. It’s certainly better than all-white casts, and it’s better than the colorblind casts of math textbooks, where Latosha has to calculate the chances that the six marbles Xiyuan drew from José’s bag would all be green. But I worry it’s skipping a step. It’s eliding over the fact that white characters, too, have a race. When race is only an issue for our characters of color, the story reinforces the idea that race is not a problem for white people. Yes, white characters should see the way their friends of color deal with race, but they too need to reflect upon and reckon with their whiteness, by the way that their worldview has been unknowingly shaped by their powerful position in the structures of white supremacy.

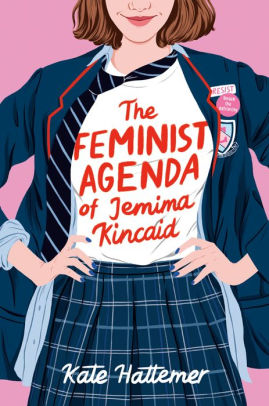

Jemima Kincaid, the white, straight, and wealthy protagonist of my new novel, is a committed feminist. She believes in justice and equity. She deeply wants to change the problematic traditions and toxic masculinity that drive the culture of her private school. But Jemima has huge blind spots. Throughout the book, she works to scrape off that cruddy crust of white feminism and internalized misogyny, but it’s there, and it’s sticky. She learns some things. She remains totally clueless about others. She is eighteen years old.

I’ve learned some things too, and I know I remain totally clueless about others. So I’ll keep reading and listening. I’ll keep thinking about how my whiteness shapes my experience of the world, and I’ll keep thinking about my white characters. Do they grow? Do they learn? Do they change? I don’t believe they have to. Literature doesn’t need a moral. But I do believe that literature should be considered, every aspect of it. If we’re going to keep writing white protagonists, we need white protagonists to reckon with race — not as something they aren’t, but as something they are.

Meet Kate Hattemer

Kate Hattemer is a native of Cincinnati, but now writes, reads, runs, and teaches high school in the DC metro area. She is the author of The Vigilante Poets of Selwyn Academy, which received five starred reviews, The Land of 10,000 Madonnas, and Here Comes Trouble. Find her online at her website, www.katehattemer.com/, on Instagram @katehattemer, or on Twitter @katehattemer.

About THE FEMINIST AGENDA OF JEMIMA KINCAID

A novel about friendship, feminism, and the knotty complications of tradition and privilege, perfect for fans of Becky Albertalli and Stephanie Perkins.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Jemima Kincaid is a feminist, and she thinks you should be one, too. Her private school is laden with problematic traditions, but the worst of all is prom. The guys have all the agency; the girls have to wait around for “promposals” (she’s speaking heteronormatively because only the hetero kids even go). In Jemima’s (very opinionated) opinion, it’s positively medieval.

Then Jemima is named to Senior Triumvirate, alongside superstar athlete Andy and popular, manicured Gennifer, and the three must organize prom. Inspired by her feminist ideals and her desire to make a mark on the school, Jemima proposes a new structure. They’ll do a Last Chance Dance: every student privately submits a list of crushes to a website that pairs them with any mutual matches.

Meanwhile, Jemima finds herself embroiled in a secret romance that she craves and hates all at once. Her best friend, Jiyoon, has found romance of her own, but Jemima starts to suspect something else has caused the sudden rift between them. And is the new prom system really enough to extinguish the school’s raging dumpster fire of toxic masculinity?

Filled with Kate Hattemer’s signature banter, this is a fast-paced and thoughtful tale about the nostalgia of senior year, the muddle of modern relationships, and how to fight the patriarchy when you just might be part of the patriarchy yourself.

ISBN-13: 9781984849120

Publisher: Random House Children’s Books

Publication date: 02/18/2020

Age Range: 14 – 17 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on BlueSky at @amandamacgregor.bsky.social.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Notes on May 2025

Cover Reveal and Q&A: Alice Faye Duncan Discusses MLK Jr. and The Dream Builder’s Blueprint

King Arthur and the Knights of Justice, Vol. 2 | Exclusive Preview

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

Pably Cartaya visits The Yarn

ADVERTISEMENT