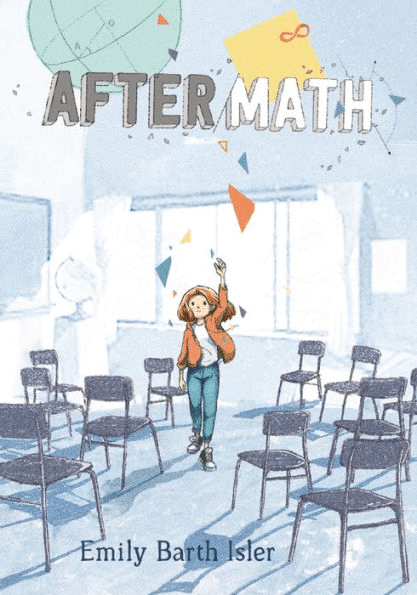

Grief and Loss in Middle Grade: An Interview with Emily Barth Isler

I’m grateful to School Library Journal for always giving me so many opportunities to dig deep into topics that interest me and interview so many wonderful authors. I wrote the cover story for SLJ’s October issue, “Good Grief: Middle Grade Authors Normalize Loss.”

SLJ and all the authors I interviewed were kind enough to allow me to share these interviews in whole here on TLT, which is so exciting to me because everyone had such great things to say and I could only share small snippets of these conversations. This article features interviews with K. A. Reynolds, Jess Redman, Gary D. Schmidt, Emily Barth Isler, Debbie Fong, Lisa Stringfellow, and Christina Li.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Please enjoy this interview with Emily Barth Isler. Be sure to check out the article in SLJ and come back to TLT for the rest of the interviews in the upcoming days.

MacGregor: What inspired or influenced the idea to center grief and loss in your story (or stories)?

Isler: As an activist working for safer gun laws in America, I became keenly aware of the way our country treats survivors of gun violence, as if, by simply surviving, they are supposed to walk away feeling lucky and nothing else. We often act like it’s a binary, as if those who don’t die in a mass shooting are inherently fine, like the options are simply life or death. Of course, we know that actually, there is an entire spectrum between those options, so many shades of pain and grief. We often do not recognize the invisible and psychological injuries from witnessing or surviving acts of violence, and thus either those survivors don’t get the care they deserve, or even if they do, they might feel very much alone in their journey processing it.

Honestly, I, myself, as a mother of a baby and a toddler at that time, was having trouble processing the realities of gun violence in America and struggling with how to cope with sending my kids to school and out into the world every day. I figured that if this was something I thought about a lot, it was likely that lots of middle grade kids were thinking about it, too. They say to “write what scares you,” and I often use my own fears and anxieties as a guide of urgency for determining what topics people need help starting conversations about.

MacGregor: A hallmark of middle grade books is offering hope to both the characters and the readers. Was this particularly challenging for you to do while tackling grief/loss?

Isler: My amazing editor, Amy Fitzgerald, encouraged me to talk more and more about therapy—we got almost all my characters into therapy by the end of the book!—which is something that has helped me process grief in real life. When I was a kid, many people didn’t talk about going to therapy, or about how it can help us cope with loss, and I hope that by putting it into the hopeful resolution of AfterMath, it contributes to the destigmatization of therapy and mental health treatment that we’re already seeing in our culture.

MacGregor: Why is it important to address tough topics like death in middle grade? (I’m thinking of all those who say things like, “Why write sad or hard books when life is hard enough?” or those who would like to “protect” children from these storylines, as though they don’t happen all the time to real actual children.)

Isler: I started to realize that even children who are not personally touched by instances of gun violence by the time they go to college or leave home are getting more and more statistically likely to encounter peers whose lives have been shaped by it. I wanted to give kids a “roadmap” and some language to use when encountering these new friends and acquaintances. Gun violence is so prevalent it’s impossible to avoid interacting with people who are affected by it, and we have to start talking about it in order to build empathy.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

In a broader sense, and especially after the pandemic, kids are encountering people struggling with loss or dealing with grief on a regular basis, whether they are aware of it or not. A lot of people have the instinct to avoid those who are hurting, as if that pain is contagious, but the middle grade years are a great time to start conversations with kids and the grownups in their lives to help them see that we cannot avoid those who are grieving, and, in fact, we should reach out to them and recognize that they are part of society more than we realize.

Parents my age and generation were so lucky to grow up in a world where school shootings were not a regular occurrence, and as a result, many of us are very hesitant to talk to our kids about them. But our kids are growing up in a different world, one where they may have Active Shooter Drills in school starting in Kindergarten. So many parents I meet tell me that their kids don’t know about the existence of gun violence, and unfortunately, teachers, librarians, and peer reviewed studies tell us that is incorrect. So I wrote AfterMath for parents as much as I did for kids—we all need a reminder that our kids are facing different realities than we did a generation before them, and we must adjust our conversations accordingly.

MacGregor: What do you hope readers take away from your book?

Isler: I know that AfterMath doesn’t provide answers to some of life’s big questions, but I do hope it acts as a conversation starter. Kids often have questions so huge they don’t know how to start those conversations with the grownups who care for them, so I hope this book and other books that deal with grief and loss help give kids the language to formulate questions. These books can also serve as a way in for adults and families who want to talk to their middle graders about hard things they encounter in the world but aren’t sure where to begin. Books are amazing conversation starters.

I also hope that readers come away from AfterMath with a broader, more expansive definition of grief. Many people think that loss and grief are synonyms for death, but there are myriad things that we humans might lose that can cause grief—the loss of experiences during the pandemic, the grief from being disappointed when we learn of our loved ones’ limitations, the sadness of growing up and seeing others in pain due to war or conflict. By understanding that all of these losses and kinds of grief exist on the same spectrum, we can develop more empathy and more ease at sitting with others as they move through their pain, or talking about our own struggles. There’s a tendency to compare or measure when it comes to grief—this is why I made AfterMath’s main character, Lucy, so enamored with math—and it’s true that some pains loom larger than others—but empathy requires that we recognize hurt and get comfortable talking about it and sitting with it.

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Exclusive Cover Reveal and Q&A: Cabin Head and Tree Head with Scott Campbell

Exclusive: ‘Aw Nuts!’ from Papercutz | News and Preview

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

Big Gretch Visits The Yarn!

ADVERTISEMENT

this article is excellent .really thank you.

hayet.