“Why Are There So Many Adults in This Room?” (Thoughts about Adult Characters in Middle-Grade Fiction), a guest post by Cathy Carr and Joanne Rossmassler Fritz

“Get the adults out of the room.” It’s one of the first pieces of advice Cathy heard at the beginning of her kidlit writing career, and many of her writing friends have a similar story. You hear it from feedback partners, from writing coaches, from agents. What the saying means is that middle-grade stories should be focused firmly on kids, with adults pushed back to secondary roles. It’s okay for the adults to make quick appearances, but they shouldn’t be too important to the story. They shouldn’t be major drivers.

But lately we’ve both noticed that fully-fledged adult characters who are intrinsic to the action are becoming more and more common in MG books. Whether it’s Franny’s Nana in Cathy’s Lost Kites and Other Treasures, Claire’s dad in Joanne’s Ruptured, or a teacher like Ms. Bowman in Barbara Dee’s Unstuck—the adults are in the room and they’re having their say. What’s going on? Why is this change happening in kidlit, and does it reflect larger changes in our culture?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Cathy—When I started reading middle grade, decades ago, the parents were often just stock figures. If they played an intrinsic role in the story, it was as a foil—those pesky grown-ups who didn’t understand anything and had to be avoided or outwitted. Lying to them was considered totally acceptable, a necessary survival technique. I still see that narrative device but I think it’s less common now. It’s not just The Dad glancing up from the TV to tell you to finish your homework, or The Mom grounding you until your room’s picked up.

Joanne—I grew up reading books like that too. In many stories, the parents were like those Charlie Brown adults who make noise in the background but were never seen.

Cathy—Yes. Vince Guaraldi used trombones to make those adult noises in the early Charlie Brown cartoons, which was perfect. Waah waaaah. I really tried to keep the adults out of the room while writing my first book, 365 Days to Alaska. I hadlimited success because the divorce of Rigel’s parents was a major plot point. I’m curious—did you hear that advice? Did it affect the way you plotted and wrote your books?

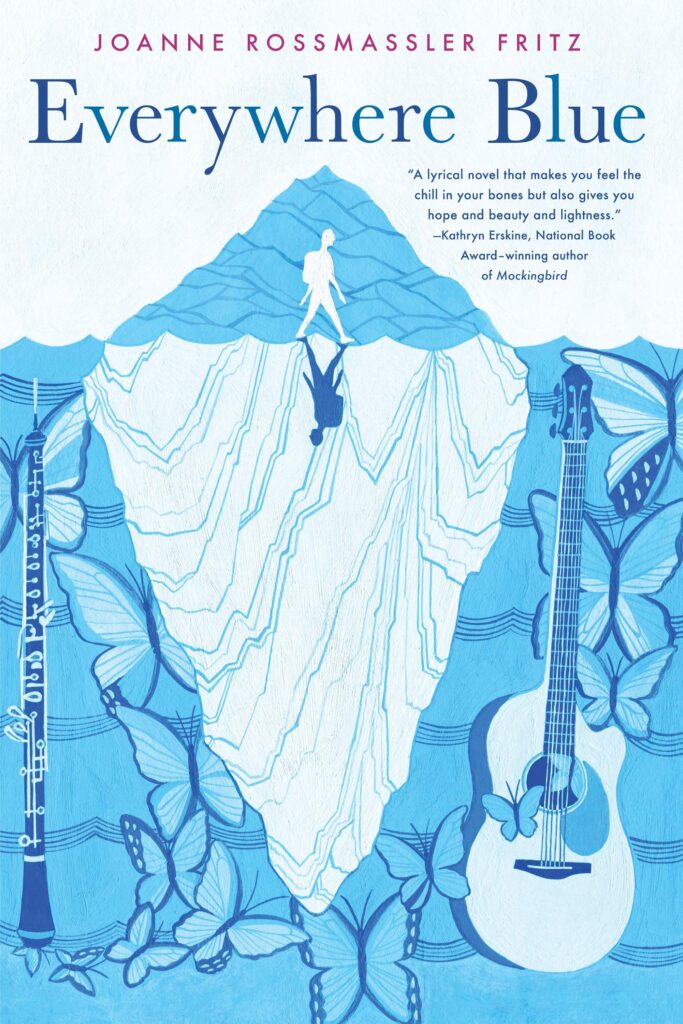

Joanne—I don’t recall hearing that advice specifically. Maybe verse novels are different. With verse novels, the main character usually tells the story in first person, and the story is always very emotional. So the main character is all-important. But I learned to write novels by writing novels (my debut novel Everywhere Blue was the fifth novel I’d written), more than through listening to other authors’ advice. And my books are always based at least in part on my own life, so perhaps it’s natural that the adults are prominent in my stories.

Cathy—I think you’ve put your finger on something important—the presence of the adults seems natural in many current MG stories because those books are realistic. My second book, Lost Kites and Other Treasures, has many major adult characters. It’s not about adults—it’s firmly about the main character, Franny, who’s twelve. But the book explores the overwhelming silence the adults in Franny’s life have maintained concerning her absent mom. That meant I couldn’t keep the adults out entirely. When Franny starts to challenge that status quo, everyone around her has to respond, grow, and change—not just Franny herself.

So maybe one simple reason for the growing presence of adult characters is the fact that we’re tackling different topics than many MG writers of a generation or two ago.

Joanne—Also, childhood has changed. I’m old enough to remember a childhood filled with plenty of free time. My friends and I were outside and on our own until dinnertime. We didn’t even have scheduled summer activities. We ran and played tag and daydreamed and caught salamanders. Our adults were distant and, frankly, not that important to our daily lives.

Cathy—I had that experience too. The free-range childhood that I enjoyed (or endured, depending on the day) is not nearly as common anymore. In many families, the adults are more present and involved in their kids’ lives on a daily and hourly basis. They drive them to and from school, they confer with their teachers, they go to all the soccer games. The fiction we write has to reflect those new truths.

Joanne—In other words, there are more adults in middle-grade fiction because the adults are around a lot more in real life.

Cathy–And they’re nosier, LOL. At the same time we need to write books that appeal to kids and reflect kids’ concerns. Do you ever feel like that’s tricky? That the presence of adults might lessen a book’s appeal?

Joanne—I think it’s something to keep in mind as we write. If we continue to write books as you and I have done, where the older characters play an important role in the kids’ lives but the kids themselves still solve their problems, that still appeals to today’s readers. I remember that one reviewer of Everywhere Blue admitted that she had wondered how I could possibly give the main character, Madrigal, agency. And she was impressed that I managed to do that. (Maddie was the only one who knew Strum well enough to know where he might go when he disappeared.)

Cathy—I agree. The kids must have agency and they need to solve their most important problems themselves. That feels truthful. Because, in their everyday lives today, kids still often need to find their own ways forward and they have to solve many of their most pressing problems themselves. And I think they’re smart enough to know that.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Interestingly, one new fictional motif I’m seeing lately are well-meaning adults who can’t leave their kids alone to figure out their stuff—who have to be restrained from writing the important essay or phoning the teacher. This was a hilarious subplot in Joshua S. Levy’s Finn and Ezra’s Bar Mitzvah Time Loop. Cynthia Kadohata says on her author website that she likes to write about children “who encounter hardship but manage to find their way forward.” “Children finding their way forward is my obsession,” she says. I share that obsession, and it’s one of the reasons I love Kadohata’s books.

Joanne–As long as we know that it’s one of the great topics of middle grade, and it continues to be front and center in our books, we’ll be doing all right.

Meet Our Guest Bloggers

Cathy Carr was born in western Nebraska and grew up in Wisconsin. Since high school, she has lived in four different U.S. states, plus overseas, and worked a variety of jobs, from burger flipping to technical writing. Wherever she goes, her observations of the natural world give her inspiration. Her debut novel, 365 Days to Alaska, was called “a wonderful debut novel about compassion, belonging, and finding your way home” by Lynne Kelly. It was a Junior Library Guild selection and chosen for Bank Street’s Best Children’s Books of the Year 2021. Her second book, Lost Kites and Other Treasures, came out in February 2024. Cathy lives in the New Jersey suburbs with her husband, son, and cats.

Joanne Rossmassler Fritz was born in Philadelphia and has worked in a publishing company, a school library, and the children’s department of a large independent bookstore. She’s been writing most of her life, but didn’t get serious about it until after she survived the first of two brain aneurysm ruptures in 2005. She is the author of two verse novels, Everywhere Blue (2021), which won the Cybils Award for Poetry, and was named an NCTE Notable Verse Novel and a Bank Street Best Children’s Book, and Ruptured (November 2023), an NCTE Notable Verse Novel, a Bank Street Best Children’s Book of the Year, and which Shelf Awareness said in a starred review, “takes on momentous subjects with delicacy and nuance.” She and her husband live in Pennsylvania and are the parents of two grown sons.

Filed under: Middle Grade, Middle Grade Fiction, Mind the Middle, Mind the Middle Project

About Karen Jensen, MLS

Karen Jensen has been a Teen Services Librarian for almost 32 years. She created TLT in 2011 and is the co-editor of The Whole Library Handbook: Teen Services with Heather Booth (ALA Editions, 2014).

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2025 Books from Sibert Winners

Fuse 8 n’ Kate: I Will Never Not Ever Eat a Tomato by Lauren Child

Betty and Veronica Jumbo Comics Digest #334 | Preview

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

ADVERTISEMENT