Dispatch From the Tortured Poets Department, a guest post by Tina Cane

As a poet, I was delighted to learn that Taylor Swift is distantly related to Emily Dickinson—sixth cousins, three times removed, to be precise. When the news broke, I was almost done writing Are You Nobody Too?—my new novel-in-verse for middle-grade readers—in which Emily Dickinson plays a central role. I was also feeling . . . well, tortured. Crunched by deadlines and the bazillion tasks of daily life, I struggled to keep my mind clear enough to write.

To be honest, struggle is an ongoing state if you’re a writer in this day and age—or any other era—which may be why the trope of “tortured poet” still exists. If you’re lucky enough to be Taylor Swift, you get to sing about it, call it a “department,” and become a billionaire. If you’re an actual working poet, you might take umbrage—like some of my colleagues did in a New York Times piece on Swift’s use of the term. Or, you might, as poet Eileen Myles does, feel a “kindred spirit in Taylor Swift’s title.” Either way, the endurance of this stereotype can be a little tedious, since it keeps poets at arm’s length and minimizes the true diversity and dynamism of contemporary poetry. I, myself, am not particularly invested in choosing a side of the fence. I’m just happy to see the word “poet” break through the algorithm, to keep alive the idea that not all good poets are dead.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

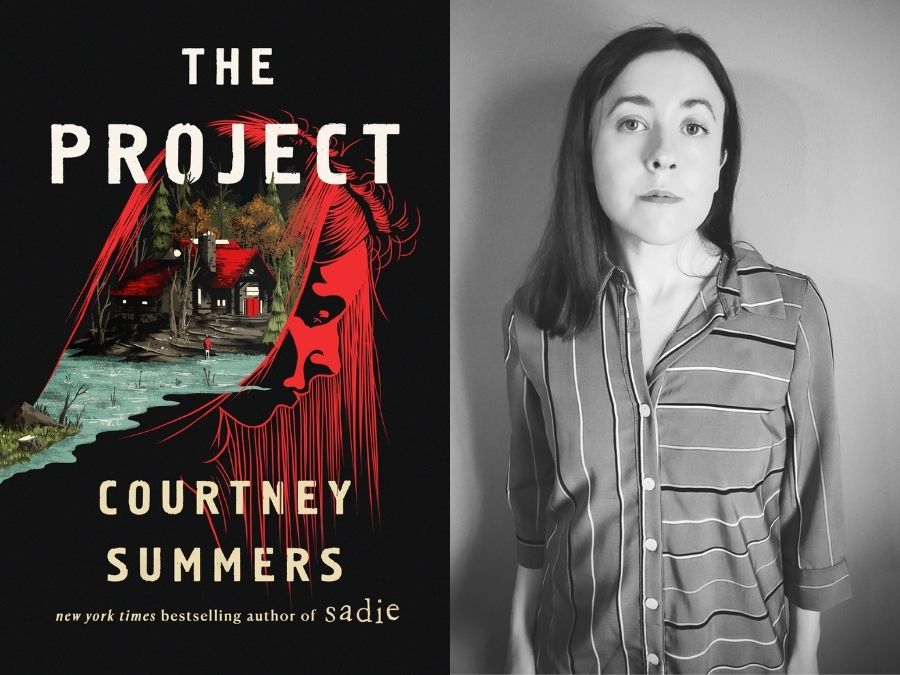

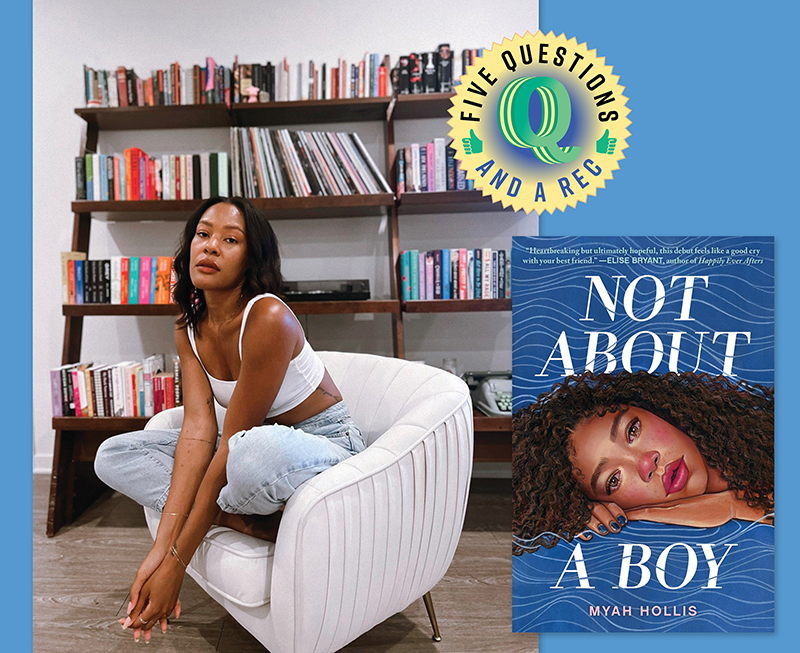

That being said, what I do know about Taylor has mostly to do with her clothes. As a follower of the kaleidoscopic Instagram homage, Taylor Swift as Books—which pairs images of book covers with pictures of Swift in coordinating outfits—I am well-versed in Taylor’s sartorial range and versatility. The project’s curator, writer Amy Long, creates matches that are witty and delightfully satisfying. The sheer number of books and outfits is awe-inspiring, and the literary endorsement heartening. When my most recent poetry collection, Year of the Murder Hornet, got “Swifted,” I was indeed quite thrilled.

As a mother of three, it seems statistically probable that one of my kids would be a “Swiftie,” and yet that angel passed right over our house. This means I can say things like “All her songs sound the same to me” without committing any kind of blasphemy. I may only recognize two of her songs, but I do still have a pulse. Like the rest of the globe, I know that Taylor Swift dominates American culture, along with a handful of others, too negligible this season to even name. Despite my ignorance of most things Tay-Tay, I recognize her incredible talent—a real musician with real songwriting skills—and remarkable business acumen. Swift’s public image cuts a stark contrast to her cousin Emily Dickinson—known by most for her reclusive nature, even by those who aren’t familiar with her poetry.

An omnipresent icon, Swift has, with this latest album, offered up the term “poet” for mass consumption and contemplation. Dickinson could probably never have envisioned such scale, or the use of “poet” in such a context. Nor could Emily have imagined she herself would be posthumously considered one of the most important American poets of all time. Much like the Dickinson who appears phantom-like to the young protagonist of Are You Nobody Too?, I like to imagine the poet’s ghost showing up on the Eras Tour. I wonder what she would make of it all. What might legions of Swift’s buoyant fans see in Dickinson?

Historically, the connection between songwriting and poetry has always been intimate. Troubadours of the Middle Ages wrote lyric poems and performed them to music at the pleasure of monarchs across Europe. In China, the oldest existing collection of poetry, Shijing—known as The Book of Songs—dates from the eleventh to seventh centuries. Its poems, too, were shared with musical accompaniment, as was most ancient poetry in Greece and beyond. Even the vocabulary is akin, as lyric—a type of poetry—is also the term for the words of a song.

Flash-forward several centuries—to 2016—and we see folk legend Bob Dylan receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature for his “poetic” contribution to the American songbook. When, at first, Dylan stayed silent about his win, he was blasted for seeming “arrogant.” He later clarified that he was just genuinely surprised: “I got to wondering how exactly my songs related to literature.” Once Bob had recovered from his shock, he expounded with a shout-out to his childhood education. Dylan praised “typical grammar school” reading for giving him “a way of looking at life, an understanding of human nature, and a standard to measure things by. I took all that with me when I started composing lyrics, and the themes from those books worked their way into many of my songs, either knowingly or unintentionally.”

For educators, like me, this statement is joyful validation. For librarians, it’s further confirmation that books matter, that the gifts of literature extend beyond school, beyond language even. While we rarely know how what we teach manifests in the lives of our students down the line, a faith that it does is what keeps us going. Further evidence that what young people read can have lasting impact is Taylor Swift’s song “The Albatross.” As a former English teacher, I am confident she wrote that song after having read—most likely in school—Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s epic poem “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” As a student of French literature, I also see parallels with “L’Albatros” by poet Charles Baudelaire, in that Swift casts herself as the tormented albatross, besieged by life (in the limelight). Either way, Swift does what artists do. She partakes in art, is inspired by it, creates work of her own, and shares it with the world.

I may not be a “Swiftie,” but I embrace Taylor’s shout-outs to literature. While I can be irrationally turned off by enterprises like “celebrity” reading clubs, I enjoy seeing a pop star pull threads from all corners of the culture. A proponent of mixing the “high” and the “low,” I have been known to characterize my own poetry as a place where one might find Cheetos alongside Rimbaud. For me, it’s as much an aesthetic choice as cultural commentary. When it comes to art, gatekeeping can be tiresome and limiting.

For educators in particular, this type of pop crossover is an opportunity. Like the hook in a song, it’s a way to reel in students and to meet them where they are. I am of the anything-that-works school of teaching. When students have their interests and tastes recognized alongside other important works, they perk up and take notice. Having come up in the 1980s—an era of punk, early hip-hop, Reaganomics, and culture wars—I recall a lot of pearl-clutching when it came to defining “real” art and deciding who could take part.

That’s why I’ll never forget Mr. Simon, the young sub who covered my tenth-grade Social Studies class, and who played us Sandinista! by The Clash. He couldn’t have known that my best friend and I were Clash fanatics. We couldn’t have known that he would tie the album to our textbook’s unit on the war in Vietnam. Within forty minutes, he was a legend. After the bell rang, we stuck around to pick his brain. Mr. Simon made our take on things feel relevant, and that suddenly made Social Studies feel relevant, too.

Last year, I wrote an essay for Teachers & Writers magazine in which I pay homage to my college professor Margaret Edwards—who wore a black cape and her hair pinned up à la Emily Dickinson. Edwards taught me how to read poetry, and we have remained friends ever since. I called the piece “Gift of the Unexpected,” partly because one day Edwards showed up to class with a boombox in hand, blaring Run-DMC’s “It’s Tricky”—which was . . . well, unexpected. It was a cut from the soundtrack of my adolescence, sure, but it was also a fresh way to offer contemporaneous examples of alliteration and rhyme. More importantly, it confirmed an approach: Things from different boxes can—and should—share space. Like Run-DMC and Richard Wilbur. Like Emily Dickinson and Taylor Swift. I am convinced that the more connections we draw across time and through cultural lines, the more we teach and create actual connection—in all senses of the word.

It’s why my novel-in-verse Are You Nobody Too? explores a girl’s attraction to and relationship with the poetry of Emily Dickinson, as she navigates waning-pandemic social anxiety at a new school. I had no idea, while writing the book, that Taylor Swift and Dickinson were distant relatives, and I didn’t know that Swift had any interest in poetry. Their relation brings to mind a moment during which my young protagonist compares her adoption experience to being “a bright thread pulled and woven into the colorful fabric” of her family. The metaphor of weaving fabric is about forging emotional bonds, but it also relates to making art. Both acts are creative in different ways, and both require a capacity for making connections. That’s why it’s wonderful for young people to see a line drawn from Taylor Swift to Emily Dickinson, from songwriting to poetry. Similar to Dickinson, who wrote in a poem, “This is my letter to the world,” Swift is sending us missives through song. When educators illuminate and validate these connections for our students, we not only foster critical thinking but also help to inspire a new generation of Taylor Swifts, Bob Dylans, and Emily Dickinsons.

Meet the author

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Tina Cane grew up in downtown New York City, and she draws much of her creative inspiration from her experiences as a city kid. The founder-director of Writers-in-the-Schools, RI, Tina was also the poet laureate of Rhode Island, where she lives with her family, who are a major source of inspiration.

Website: https://www.tinacane.ink/about.html

About Are You Nobody Too?

After years of discomfort as the only Chinese student at her private middle school, Emily transfers to Chinatown’s I.S. 23 for 8th Grade and ends up feeling more disconnected than ever. In this coming-of-age novel-in-verse, will Emily be able to find her way or will she lose herself completely?

After a year of distance-learning, Emily Sofer finds her world turned upside down: she has to leave the only school she’s ever known to attend a public school in Chinatown. For the first time, Emily isn’t the only Chinese student around…but looking like everyone else doesn’t mean that understanding them will be easy—especially with an intimidating group of cool girls Emily calls The Five.

When Emily discovers that her adoptive parents have been keeping a secret, she feels even more uncertain about who she is. A chance discovery of Emily Dickinson’s poetry helps her finally feel seen. . . but can the words of a writer from 200 years ago help her open up again, and find common ground with the Five?

ISBN-13: 9780593567012

Publisher: Random House Children’s Books

Publication date: 08/27/2024

Age Range: 10 – 13 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on BlueSky at @amandamacgregor.bsky.social.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Who’s Waldo? 6 Seek-and-Find Finds for 2025

Myrick Marketing Publishing Summer & Fall 2025 Preview – Part One: Floris Books, Gecko Press, and Helvetiq

Junie B. Jones and the Stupid Smelly Bus: The Graphic Novel | Review

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

Pably Cartaya visits The Yarn

ADVERTISEMENT