From Exclusion to Belonging, a guest post by Sarah-SoonLing Blackburn

Over the past few years, the STAATUS index survey has asked Americans to name a famous Asian American. For three years in a row the most common response has been “I don’t know.” Number 2 has been Jackie Chan, who is not American, and number 3 has been Bruce Lee, who has been dead for more than fifty years.

I speak with many Asian American kids and adults across the United States, and a common theme that comes up in these conversations is invisibility. This includes feeling overlooked, having others make assumptions about their personalities and skill-sets based on stereotypes, and being regularly mistaken for other Asian people. And, critically, it includes a glaring lack of representation in history and literature instruction. Most Americans do not learn many, if any, Asian American histories and stories in school. In this absence, it’s no wonder that “I don’t know” remains at the top of our nation’s popular consciousness.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

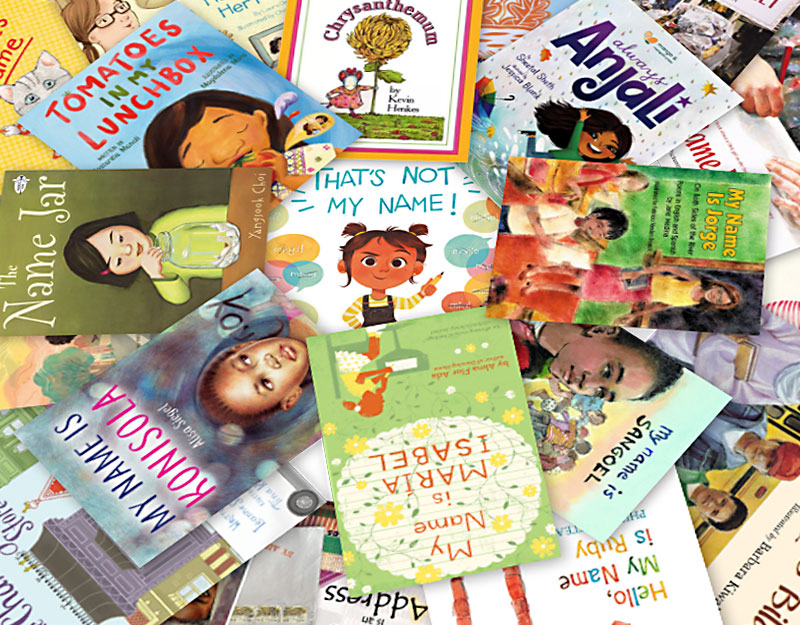

As a teacher, I loved finding books for my classroom library that provided mirrors for my students’ beautiful, complex, and varied identities. This was also one of the hardest parts of my job. There are some experiences and identities that show up frequently in children’s literature, while others rarely show up at all or are focused on a small set of tropes and tragedies, rather than the full breadth and range of human experience.

After I’d left the classroom and had a job training teachers on classroom culture, it became increasingly clear to me that students who had meaningful reflections of themselves in their classrooms had more trusting relationships with their teachers, were more engaged in their learning, and were more likely to say they enjoyed coming to class each day. It was around this time that I first picked up Celeste Ng’s Everything I Never Told You. I devoured it, rocked by a sensation that this was my first time experiencing a real mirror.

“So this is what it feels like,” I remember thinking. This sense of familiarity, this revelation in seeing myself in the pages of a book, this was what my second grade teacher had thought she was giving me when she pressed Tikki Tikki Tembo into my hands. All this time I’d been trying to make sure our students had mirrors, and I’d been lacking them myself.

I think about this quote from Junot Diaz quite often: “You guys know about vampires? … You know, vampires have no reflections in a mirror? There’s this idea that monsters don’t have reflections in a mirror. And what I’ve always thought isn’t that monsters don’t have reflections in a mirror. It’s that if you want to make a human being into a monster, deny them, at the cultural level, any reflection of themselves.”

In 2020 Covid spread, and a wave of anti-Asian sentiment spread in its wake. In the absence of proper reflections of Asian Americans, the invisibility left easy room for the “I don’t know” to take on a monstrous shape. Old “yellow peril” stereotypes, and longstanding tropes of disease-ridden Chinese people in particular, rapidly reared their heads. In the months and years that followed, I spoke with many families and educators who shared stories of Asian kids being told they were monstrous. “My mom says I can’t sit with you anymore.” “Your weird food is what made everyone sick.” And, in the absence of counter narratives, some kids started to internalize and believe these things. “If you want to make a human being into a monster, deny them, at the cultural level, any reflection of themselves.”

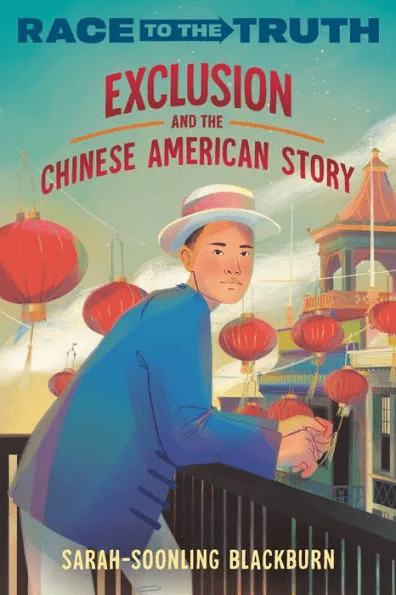

But I’m an optimist by nature, and I know that invisibility does not have to be a permanent state. Researching and writing Exclusion and the Chinese American Story turned out to be quite a healing experience, and I hope that readers find the same in its pages. I got to share some of my work with a group of Asian American high school students a couple of years ago, and their reflections have stuck with me.

It might seem, in a moment of contemporary racism, that learning about historical racism would be even more depressing. The students told me that it had the opposite effect. Realizing that our current moment has deep historical roots helped them understand that the current racism has nothing to do with anything they or their families have done wrong. It also helped them see that there have always been people who have resisted, and to think about ways that they, too, would like to address the injustices they experience or learn about in their own lives.

The students felt frustrated that they hadn’t learned these histories. They wondered why some histories are told more often than others, and it made them wonder what other histories they might not yet have been exposed to. Their frustration quickly turned into curiosity to learn more, and a strong commitment to advocate to their teachers to teach more lesser taught stories, Asian American and otherwise. As we expose kids to mirrors, it can help them also want to seek out windows into experiences they might not have previously considered.

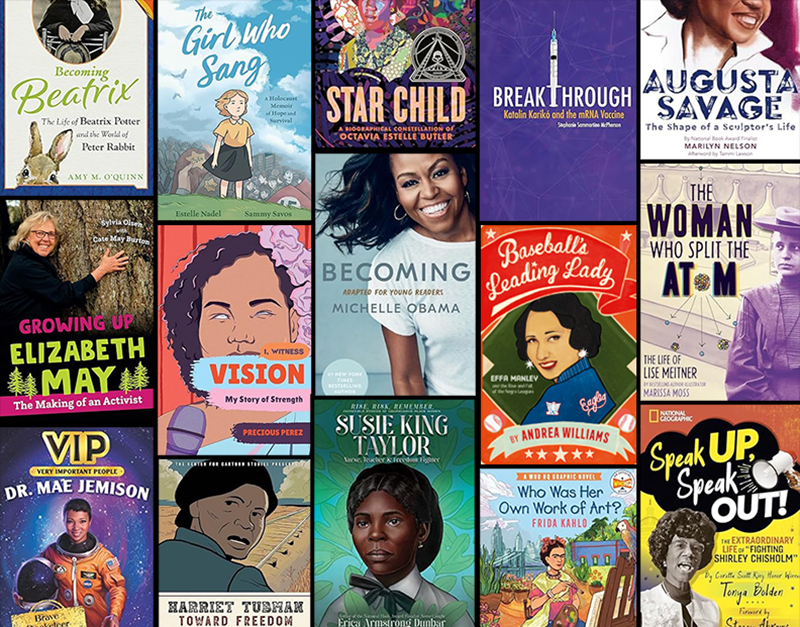

Books like Exclusion and the Chinese American Story and the rest of the Race to the Truth series are just a starting point. There’s no way to tell all of a group’s history in a single volume. The students were quick to ask for other places that they can turn to learn more. I’ve been working on having ready recommendations at my fingertips, based on what I know about the person who is asking. Podcasts like Asian American History 101 and Blood on Gold Mountain, documentaries like Asian Americans, and books like From a Whisper to a Rallying Cry, Angel Island: Gateway to Gold Mountain, and American Born Chinese provide a range of genres, time periods, and modes of engagement for learning more.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

“Exclusion” might be in the title of my book, but at the end of the day it’s really a book about belonging. Yes, it focuses on Chinese Americans who historically fought for and found belonging in the United States, but, perhaps more importantly, it can help readers understand that Chinese Americans belong here today. This matters for every reader, but it might matter most for those of us who have too often felt invisible. After all, when we can finally see ourselves in a mirror, we can know that we are far from monstrous.

Meet the author

Dr. Sarah-SoonLing Blackburn is an educator, speaker and professional learning facilitator. She was born in Bangkok, Thailand into a mixed-race Malaysian Chinese and white American family. A classic “third culture kid,” she grew up moving between various East and Southeast Asian countries and the Washington DC area. Sarah moved to the Deep South in 2009, and she has now lived there longer than anywhere else. Her experiences first as a classroom teacher and then as a teacher educator inform her beliefs about the role that education can and must play in the realization of social justice.

She owes very much to her ancestors.

Sarah spent most of her years in the classroom teaching third and fourth grade. As a professional trainer, Sarah’s areas of focus have included workplace cultures, leadership skills, and diversity, equity and inclusion. Sarah has an M.A. in Social Justice and Education from University College London’s Institute of Education. Her doctoral research at Johns Hopkins University explored strategies for retaining rural educators, and her Ed.D. specialization was Instructional Design in Online Teaching and Learning. She is based out of Oxford, Mississippi.

Website: https://www.sarahsoonling.com/

Instagram: @SarahSoonLing

About Exclusion and the Chinese American Story

Until now, you’ve only heard one side of the story, but Chinese American history extends far beyond the railroads. Here’s the true story of America, from the Chinese American perspective.

A Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selection

If you’ve learned about the history of Chinese people in America, it was probably about their work on the railroads in the 1800s. But more likely, you may not have learned about it at all. This may make it feel like Chinese immigration is a newer part of this country, but some scholars believe the first immigrant arrived from China 499 CE—one thousand years before Columbus did!

When immigration picked up in the mid-1800s, efforts to ban immigrants from China began swiftly. But hope, strength, and community allowed the Chinese population in America to flourish. From the gold rush and railroads to entrepreneurs, animators, and movie stars, this is the true story of the Chinese American experience.

ISBN-13: 9780593567647

Publisher: Random House Children’s Books

Publication date: 03/26/2024

Series: Race to the Truth

Age Range: 10 – 12 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT