Writing in the Margins, a guest post by Parisa Akhbari

The first main character I ever wrote was white. I was ten years old and had just read my mom’s childhood copy of Nancy Drew: The Secret of the Old Clock, and wanted to try my hand at mystery writing. The character in question–Morgan Taylor–was a ten year old, like me, but with light brown hair, white skin and a distinctly American name.

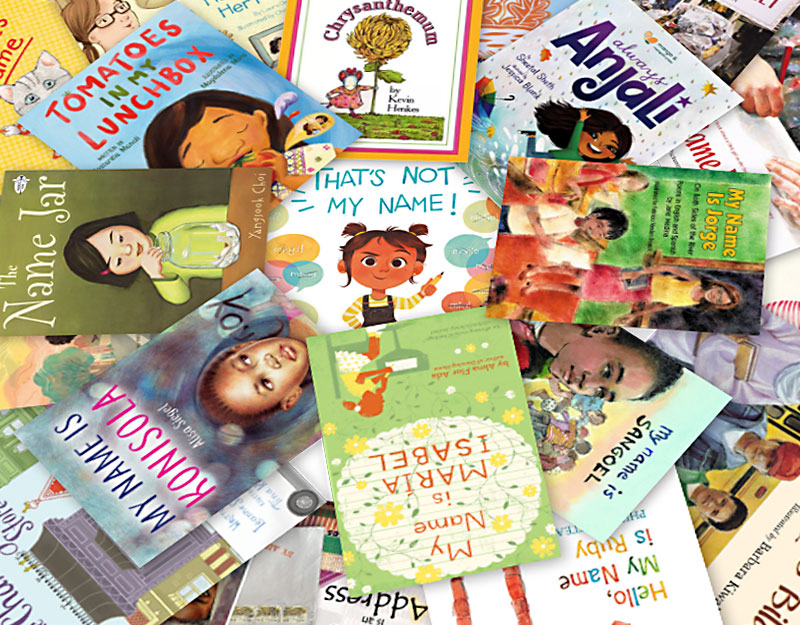

The choice was a reflexive and unconscious one for me. It had never occurred to me to dream otherwise. In every book around me–from Sharon Creech to Sarah Dessen to Judy Blume–the characters were white, thin, presumed straight, and nondisabled. The implied message was clear: these were the characters everyone could relate to. The ones whose stories and voices mattered.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Whenever I encountered marginalized voices in books growing up, they were mired in historical tragedy and violent oppression: kids in Japanese imprisonment camps, kids surviving the horrors of slavery or the Holocaust, queer adults facing HIV and the AIDS crisis. These stories were and are vital for young readers. But when they become the only narratives that gatekeepers allow young readers to access, readers from marginalized backgrounds can begin to believe that there is no story, no future in which they can lead a life of hope, optimism, and joy.

I still remember the first glimmer that suggested queer stories could be more than tragic. I was thirteen, and my mom brought home a signed copy of a book she’d happened upon while perusing the bookstore. Glimmer is the right word–it was barely a flash toward the end of the book, a hint lingering on the last few pages suggesting the teenage protagonist had a crush on her girl friend. The rest of the book has been blurred by time in my memory, but those few pages are crisp at the surface of my mind. The weight of the book in my hands, the layout of those glimmering sentences, the scene as I imagined it unfolding in my vision, even my spot on the white floral bedspread on my bunk bed. My mom hadn’t read the book before handing it off to me, and I remember wondering what would happen if she found out how it ended.

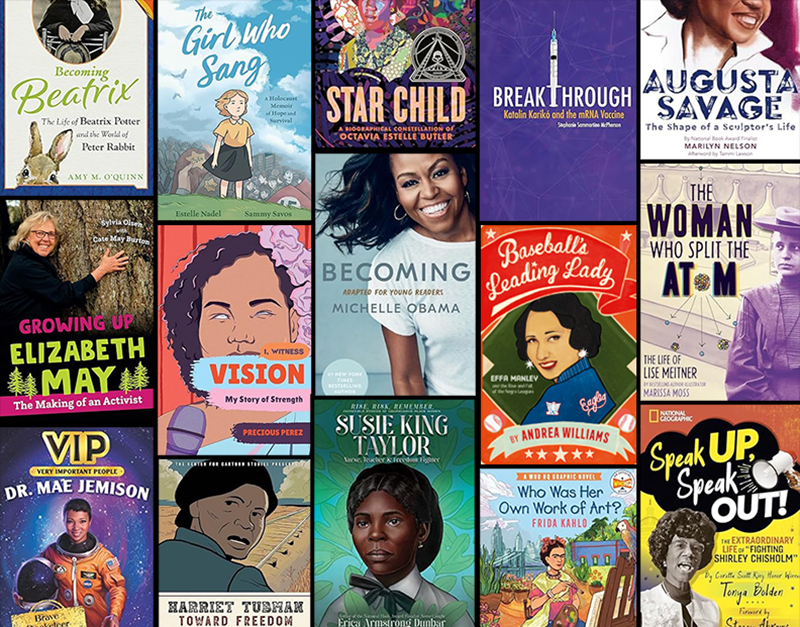

It was another decade before a book ignited the belief that I could write characters who looked and felt like me. I read Sara Farizan’s first two novels, and for the first time saw glimpses of myself. Her characters uttered Farsi endearments over dinner, their tables laden with tahdig and khoresht. They agonized over crushes on girls who the world had told them were off limits. Like the dozens of little mirrors my bibi jaan embroidered into my dress, each sentence flared with a reflection, a small truth about my own life. Through these stories, Farizan painted vivid images of girls like me. They took up space, leading big, main-character lives, and they had hopeful, promising futures. Their existence–even in fiction–made me realize there were others like me.

From that point on, my characters ceased defaulting to white. Instead of writing from a voice our culture validates as worth listening to, I wrote from the voice I wish I’d heard when I was seventeen, thirteen, ten years old. I stopped worrying about whether white audiences would understand the Farsi words and Iranian cultural norms peppered throughout my writing, and started listening for the particularities blossoming at the intersections of my existence.

The response was mixed. Writing from my positionality led me to my terrific agent, but it also led some white readers to label a protagonist who shared my identities a self-insert–despite the fact that white, straight male authors have been writing white male protagonists for generations. Feedback from some suggested that, while they found the writing beautiful, the story was viewed as not marketable or not commercial enough because of a perceived lack of readership for intersectional narratives.

I did not buy into the belief that intersectional experiences, though granular, are unrelatable to a wider audience. In my career as a therapist, I’ve come to appreciate the universality of emotions. No matter our cultural upbringings, humans all experience sadness, fear, and joy. Teen readers devoured The Hunger Games not because they had first-hand experience fighting others in a televised battle to the death, but because they understood fear, grief, desperation, and hope. If white, straight readers could imagine their way into the realities of The Hunger Games or The Fault in Our Stars or Divergent, they can also resonate with the emotional truths of intersectional narratives.

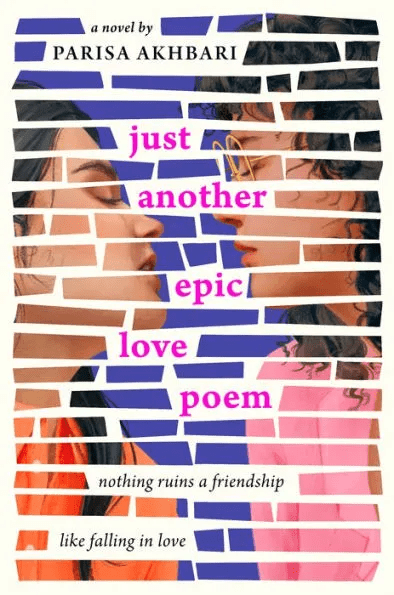

In writing my contemporary YA novel, Just Another Epic Love Poem, I leaned into the granularity of my experience. I wrote my way toward the nuances in relationships that felt uniquely queer to me, exploring the blurred line that the main character, Mitra, navigates between friendship and romance with her best friend, Bea. What does a touch or a hug mean when coming from a best friend she’s also secretly in love with? How will Mitra navigate sleepovers with her best friend when they mean something more to her, churning up all kinds of complicated feelings? How can Mitra say I love you to Bea in a way that sounds friendly, when romantic feelings bubble up under the words? These questions all speak to the particularities of queer adolescence, but they resonate with emotions many can relate to: longing, confusion, heartache.

I also wrote toward the heart of my own struggle with spirituality as a teen. As an Iranian American, closeted queer kid in Catholic school, I often felt bisected by the definitions of spirituality offered to me. God was all-powerful, all-knowing, loving and kind, but would not accept my sexuality or my Muslim family members. In Just Another Epic Love Poem, Mitra travels the borders between the expressions of spirituality around her. She makes found poems out of psalms in church, but finds divine guidance from the ancient Persian poet, Hafez. She absorbs Bible verses that condemn her as broken and destructive, and also absorbs verses of a poem, “Kindness,” that spark her capacity for self-compassion. Mitra’s coming-of-age journey travels the borders of her identities, like a needle and thread stitching them whole.

As early readers share their responses to Just Another Epic Love Poem, I’m heartened to see people across a broad spectrum of identities connecting to Mitra’s story. Using Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop’s metaphor for children’s literature, for some readers, my novel is a mirror, and for others, it’s a window. Either way, when readers enter Mitra’s world, they’ll find themselves steeped in the potent emotions that make us human.

Meet the author

Parisa Akhbari is a writer and mental health therapist from Seattle, Washington. When not writing or therapizing, she can be found trying to replicate her grandmother’s drool-worthy Persian recipes, hanging out with the disability community, and marathoning sci-fi movies with her partner and dogs. Just Another Epic Love Poem is her debut novel.

About Just Another Epic Love Poem

Best friendship blossoms into something more in this gorgeously written queer literary romance.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

“The heartache and longing of witnessing a beloved character pine hopelessly over her best friend has never brought me this much unadulterated joy.” –National Book Award Finalist Sonora Reyes, author of The Lesbiana’s Guide to Catholic School

Over the past five years, Mitra Esfahani has known two constants: her best friend Bea Ortega and The Book—a dogeared moleskin she and Bea have been filling with the stanzas of an epic, never-ending poem since they were 13.

For introverted Mitra, The Book is one of the few places she can open herself completely and where she gets to see all sides of brilliant and ebullient Bea. There, they can share everything—Mitra’s complicated feelings about her absent mother, Bea’s heartache over her most recent breakup—nothing too messy or complicated for The Book.

Nothing except the one thing with the power to change their entire friendship: the fact that Mitra is helplessly in love with Bea.

Told in lyrical, confessional prose and snippets of poetry Just Another Epic Love Poem takes readers on a journey that is equal parts joyful, heartbreaking, and funny as Mitra and Bea navigate the changing nature of I love you.

ISBN-13: 9780593530498

Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

Publication date: 03/12/2024

Age Range: 14 – 17 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT