Writing About Broken Worlds, a guest post by Veera Hiranandani

Resilience. It’s a word used often in difficult times, especially by educators, therapists, parents, and others who support and care about children. As adults, we value the ability to get through difficult things and recover quickly and we try to help children develop these skills. As a parent, I want my kids to be able to handle failures, disappointments, and loss because I know they’re going to experience these things. Ultimately, we want our kids to be okay. But sometimes things go beyond the categories of common heartache. Sometimes the heaviness of the world gets too big to hold.

So how do we write about our broken world for young people, both from a historical perspective or in a contemporary setting? Books can be so many things for children, just like any diverse landscape of literature, giving children an array of experiences to choose from—lighter topics, humor, exciting fantasy realms, and grand adventures all need to be part of the menu, along with the heavier stuff.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

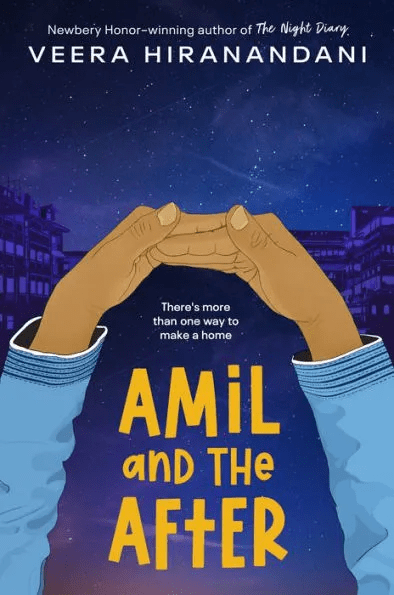

In my new book, Amil and The After, I continue the story I started in my previous book The Night Diary. My characters find themselves in post-partition 1948 Bombay (now called Mumbai) and we see from a young boy’s point of view how he and his family try to rebuild their lives only months after fleeing their home in Pakistan. I wanted to look at what happens after we survive something very difficult. How are we both wounded and strengthened by the experience? What else besides resilience might be needed?

Amil and his twin sister, Nisha, are resilient because they don’t have much of a choice. At times, Amil is grateful for his life, but at other times he feels a sharp sense of loss and confronts, with his sister, feelings of post-traumatic stress from their harrowing journey. He has also lost some trust in the world and longs for his simpler life back in Pakistan. He wants to hang out with friends, ride around carefree on his very own bicycle, go to the cinema, and buy tasty chaat from the food carts. He just wants to be twelve.

Amil knows he’s lucky because he has a family, a home, and a school to go to, but he also wonders if it’s okay to be okay when he’s very aware others are suffering on a greater level. Amil tries to talk about what he’s feeling, but his father, a busy doctor, is unable to provide the empathy and understanding that Amil is looking for. To Amil’s relief, he discovers that his sister Nisha shares some of his feelings. At her suggestion, he expresses himself in a drawing journal for his mother who died when he was a baby. As the story progresses, Amil also finds a way to help someone having a harder time.

Writing about a topic like the Partition for young people isn’t about showing all of the violence and unimaginable trauma that happened, but rather it’s about shedding light on some of its complex emotional truth. All of these things—connection, art, helping others, and understanding how the past has affected him–lead Amil down a richer, more hopeful path beyond simply moving on.

After the Partition, my father’s family also had to leave their home in Pakistan and eventually settled in Bombay/Mumbai. I often think about what my father, grandparents, aunts, and uncles endured. I also think about what happened after they left Pakistan and started new lives as refugees and Partition survivors. What were those first few years like?

Though they were lucky in many ways, I don’t think my father was encouraged to share what he felt about the huge and scary upheaval he and his family went through. There was only room for resilience. I’ve wondered if my conversations with him during my research for both Amil and the After and The Night Diary were one of the first times he felt free to reflect deeply on his childhood as his whole self.

I wrote this book during the second and third year of the pandemic and channeled into the story some of the emotional truth I experienced during the collective trauma of that first pre-vaccinated year of Covid with its lockdowns and the looming fear that I or another family member could fall seriously ill or worse. I parented my kids through virtual school, masking all day, and restricted social freedom. I watched them grapple with the isolation, fear, and sadness just like I was doing.

They did become more resilient, but they also lost some of their innocence and trust in the world. To be honest, so did I, and the repercussions are very much with us. My family has gone back to our regular lives in many ways, but we’re not the same and neither is the world. It reminds me of a line from the very wise and popular poem by Maggie Smith, “Good Bones” when she says, “Life is short and the world is at least half terrible, and for every kind stranger, there is one who would break you, though I keep this from my children.”

Even if we wish we could, especially as our children get older, it becomes harder to keep the “half terrible” part from them. They see the news headlines of global suffering, violence, and war on devices we all hold in the palms of our hands. For those of us who are lucky enough to stay safe and survive, how do we continue to process it all? Focusing on concepts like resilience can make us feel better or perhaps more in control, but if that idea is centered over everything else, it can increase the sense of isolation for children especially when they’re struggling. We also need to allow space for sadness, anger, fear, vulnerability, and normalize a mix of feelings. That’s how we access and know our whole selves.

Perhaps if our kids see examples in stories of both children and adults handling multiple emotions in the face of adversity, if they see that healing and finding joy again is not linear and different for everyone, the easier it might be for them to make sense of the world and feel connected to it.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

My father’s childhood messages that told him to keep moving forward and leave the bad things behind as fast as possible made sense for the times. In many ways, it has served him well. He has a steady strength and practical way of looking at the world that I’ve always admired, but I’ll never know fully what had to get pushed under the rug in order for him to keep going. Partition survivors from his generation do not always want to revisit painful and traumatic memories, but sometimes we all need an invitation to a space where we can be our whole messy selves, no matter how old we are. I hope for this book to be one such invitation.

Meet the author

Veera Hiranandani, author of the Newbery Honor–winning The Night Diary, earned her MFA in creative writing at Sarah Lawrence College. She is the author of The Whole Story of Half a Girl, a Sydney Taylor Notable Book and a South Asia Book Award finalist, and How to Find What You’re Not Looking For, winner of the Sydney Taylor Book Award and the New York Historical Society Children’s History Book Prize, and most recently, Amil and The After. A former editor at Simon & Schuster, she now teaches in the Writing for Children and Young Adults MFA Program at The Vermont College of Fine Arts.

About Amil and the After

A hopeful and heartwarming story about finding joy after tragedy, Amil and the After is a companion to the beloved and award-winning Newbery Honor novel The Night Diary, by acclaimed author Veera Hiranandani

At the turn of the new year in 1948, Amil and his family are trying to make a home in India, now independent of British rule.

Both Muslim and Hindu, twelve-year-old Amil is not sure what home means anymore. The memory of the long and difficult journey from their hometown in what is now Pakistan lives with him. And despite having an apartment in Bombay to live in and a school to attend, life in India feels uncertain.

Nisha, his twin sister, suggests that Amil begin to tell his story through drawings meant for their mother, who died when they were just babies. Through Amil, readers witness the unwavering spirit of a young boy trying to make sense of a chaotic world, and find hope for himself and a newly reborn nation.

ISBN-13: 9780525555063

Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

Publication date: 01/23/2024

Age Range: 8 – 12 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Endangered Series #30: Nancy Drew

Research and Wishes: A Q&A with Nedda Lewers About Daughters of the Lamp

Cat Out of Water | Review

ADVERTISEMENT