Looking Outside Your World: A Message from my Middle Grade Debut, a guest post by Rhonda Roumani

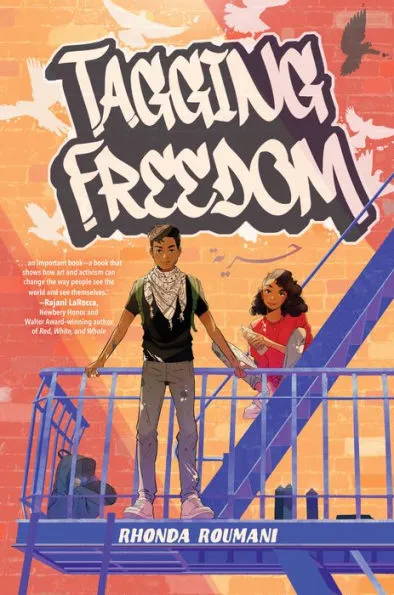

Last week, my debut Upper Middle Grade novel TAGGING FREEDOM came out. It’s a novel about how art, combined with activism, can change the world. It’s about the importance of protest, people’s inherent need for freedom, and why we must care about people and issues that exist outside our own smaller worlds.

Over the last week, at book events and at schools, I have been asked, why did you write this book? And I never have time to give the full answer. I wrote it for my children. I wanted them to understand why we haven’t been able to visit Syria. I wanted them to understand that the war that ravaged Syria and the ensuing refugee crisis did not start off that way. It started off as a revolution, as a call for freedom. I wrote it because when I ran my daughter’s book fair at her school many years ago, I couldn’t find a single book written by an Arab or Arab American author, and I found only one book with a Muslim character and that book was about Malala Yousafzai.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I also wrote it because of what was happening here in the United States. Most of TAGGING FREEDOM, in fact, takes place in the United States. Kareem, my 13-year-old Syrian character, starts the book by graffitiing messages of freedom around Damascus with his friends. But when he almost gets caught by the country’s secret police, his parents send him away to live with his cousin in the United States. In the US, Kareem feels alienated and alone. Nobody understands what his country is going through. Nobody around him understands what it feels like to constantly worry about his family and friends. His parents, who are doctors, stayed back in Syria to care for their communities. As the situation gets more precarious, he feels more and more isolated.

He also knows he cannot just sit down and remain silent. He has to do something. He can’t exist in the silence of a small town when he knows what is happening back home. So he brings his messages of freedom and protest to his Syrian-American cousin’s small Massachusetts town with graffiti chalk.

I met many Syrian activists like Kareem both in Syria and in the United States. It is not a mistake that Kareem has a clarity of vision in my book. Just as it is not a mistake that Samira, my Syrian American main character, is worried about finding her place in her world.

A few years ago, I was the PTA president at my daughter’s school. My daughter was still young, but the older kids wanted to hold a walk out for a Global Climate strike led by Greta Thunberg. When the kids approached the principal, the principal said no, citing safety concerns. When the parents tried to change the principal’s mind, she doubled down. It ended up the subject of a heated PTA meeting. In the end, the parents left the meeting fuming and the students didn’t walk out.

But I imagined a different outcome. And I wrote TAGGING FREEDOM with this outcome in mind. It is what Kareem would have done. What if the kids have walked out anyway? And maybe received detention? And what if the parents told their kids that this “punishment” should be worn as a badge of honor. That standing up for freedom sometimes does have consequences. In this case, the consequences are small. In other cases, they are much bigger.

That is what protest is. Protest is not limited by authority. One of the slogans Kareem tags around his Massachusetts town in my book is “FREEDOM REQUIRES NO PERMISSION.”

I wrote this book for kids, but I hope adults pay attention too. We all could learn from Kareem.

Over the last month, I have been a part of Muslim and Arab spaces that are mourning. Israel’s war on Gaza has left us gutted. We cry daily as the death count rises, with more than 10,500 Palestinians dead, including more than 4,000 children. I personally know two friends who have lost their entire family in Gaza, 16 and 20 people respectively, in one night. The massive loss of civilian life, and the resulting silence, makes us feel like, once again, Arab and Muslim lives don’t matter.

And, once again, we feel like our stories are being censored. Last week, four author friends, including myself, had their school visits canceled or postponed. Some of us have been given reasons. Others have received no explanation. But shutting out our voices and washing our hands of the problem is not the answer. Kareem and Samira would know that we cannot stay silent.

For decades, Muslims and especially Arabs have struggled to get our story out into the world.

According to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center from the School of Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (which tracks diversity statistics in children’s literature and started tracking Arab as a category in 2011), books by Arab authors or illustrators made up only 0.9 percent of the books released in 2022. Meanwhile, books with a primary Arab main character or subject made up just 0.6 percent of books; and books about Arab issues made up 0.7 percent of the books released.

Librarians and teachers, with a single book, can open up a child’s world to new ideas, new people, new ways of thinking. You are at the forefront of the battle against book bans, and as authors, we rely on you to speak up against them. So I ask you during this difficult time, please make sure Arab and Muslim stories are not being censored in your schools. And please do not cancel events for Palestinian and Arab authors. (I’m including a list of books to include in your libraries or classrooms. There are many more, like the Farah Rocks series by Susan Muaddi Darraj, and Ida in the Middle by Nora Lester Murad.) Canceling might be the easiest way to avoid conflict, but is not the right way. Canceling only leads to further misrepresentation and isolation.

My school visits have been the best part of my publishing experience so far. I’ve talked to students about Syria, revolution, freedom, graffiti and what it feels like to grow up between two cultures. The students are curious and smart. And the more they know about all our communities, the more power they will have to one day tackle our world’s problems.

And, please, don’t forget to check on our children in your schools. Even if they are not showing it, they are hurting too.

Meet the author

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Rhonda Roumani is a Syrian American journalist who lived in Syria as a reporter for U.S. newspapers. She has written about Islam, the Arab world, and Muslim-American issues for more than two decades. Currently, she is a contributing fellow at the Center for Religion and Civic Culture at USC. Rhonda lives in Connecticut with her family.

About Tagging Freedom

Out of the revolutions across the Arab world comes this inspirational story of hope, freedom, and belonging, perfect for fans of Other Words for Home and A Good Kind of Trouble.

Kareem Haddad of Damascus, Syria, never dreamed of becoming a graffiti artist. But when a group of boys from another town tag subversive slogans outside their school, and another boy is killed while in custody, Kareem and his friends are inspired to start secretly tag messages of freedom around their city.

Meanwhile, in the United States, his cousin, Samira, has been trying to make her own mark. Anxious to fit in at school, she joins the Spirit Squad where her natural artistic ability attracts the attention of the popular leader. Then Kareem is sent to live with Sam’s family, and their worlds collide. As graffitied messages appear around town and all eyes turn to Kareem, Sam must make a choice: does she shy away to protect her new social status, or does she stand with her cousin?

Informed by her time as a journalist, author Rhonda Roumani’s Tagging Freedom is a thoughtful look at the intersection between art and activism, infused with rich details and a realistic portrayal of how war affects and inspires children, similar to middle grade books for middle schoolers by Aisha Saeed, The Night Diary by Veera Hiranandi, or Refugee by Alan Gratz.

ISBN-13: 9781454950714

Publisher: Union Square Kids

Publication date: 11/07/2023

Age Range: 8 – 12 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Endangered Series #30: Nancy Drew

Research and Wishes: A Q&A with Nedda Lewers About Daughters of the Lamp

Cat Out of Water | Review

ADVERTISEMENT