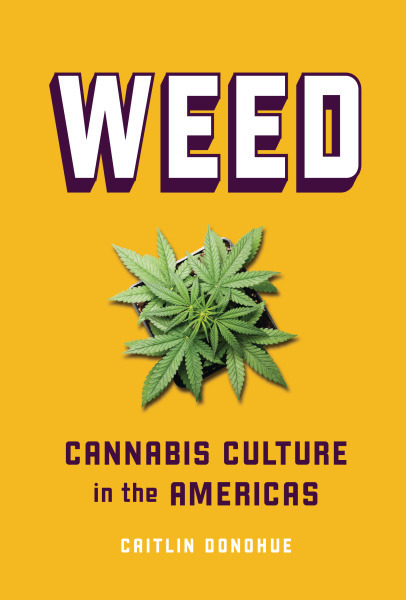

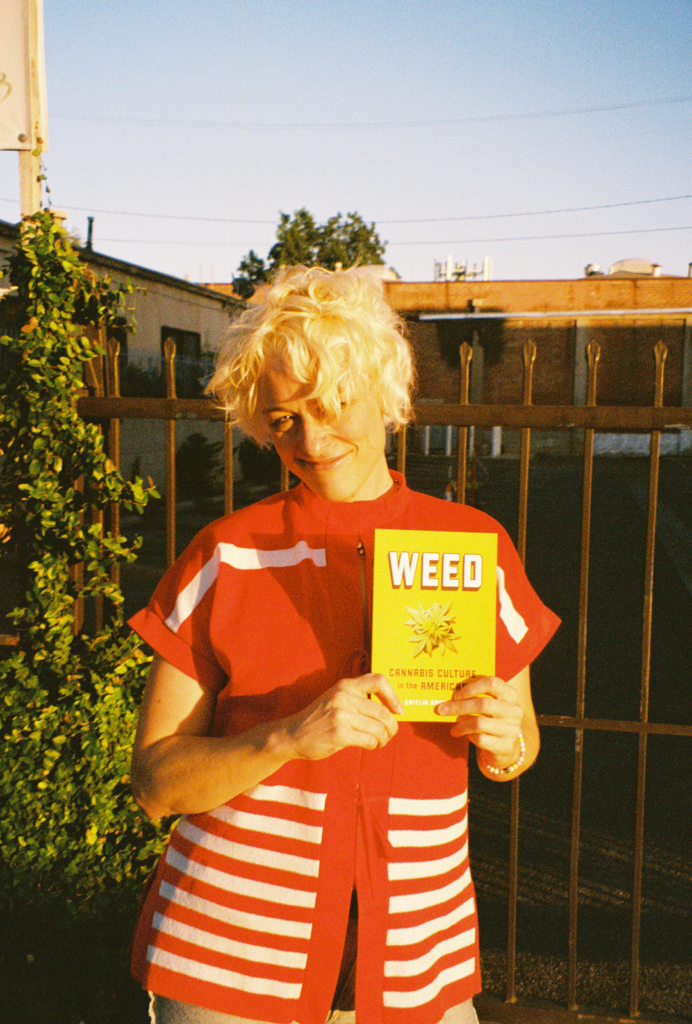

The Weed Tour – A Diary of Travels, a guest post by Caitlin Donohue

For many teens and their parents—OK, for nearly all of us—navigating the fear and ignorance around drugs to talk about our experiences with them can be excruciating. That’s part of the reason why I wrote my book Weed: Cannabis Culture in the Americas. After 14 years of working as a drug journalist, it’s become clear that we need to radically rethink the way we talk about psychoactive substances with young people—OK, with all people.

What is a drug? Everything from refined sugar to fentanyl to coffee to pharmaceuticals. Who takes drugs? Pretty much everyone you know. Where does that leave “just say no to drugs” style education? In cruelly stigmatizing, egregiously unscientific, and dramatically contradictory territory. In Weed, cannabis does indeed serve as a “gateway drug.” No, not in that outdated and disproven sense that marijuana consumption “causes” people to experiment with other psychoactive substances. Rather, the book uses a drug that has seen some progress towards normalization to open conversations about our relationship to all substances, the everyday legal ones and the most harshly stigmatized ones alike.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Believe me, I understand that writing for teens about cannabis in any way that goes astray of “DON’T DO IT” is pretty radical territory. Organizing #WEEDTOUR was nerve-wracking. I planned on hosting conversations about youth drug education up the West Coast of the US and Canada, and back down to where it was written in Mexico City. Would we receive “backlash” to the events, as the owner of one small-town bookstore mused? (Given the current rash of book-banning in the US, couple with the fact that Instagram limits my posts every time I posted the title of the book alone, this seemed possible.)

Would anyone even show up?

Dear YA librarians, they did.

I had underestimated the collective need we have in 2023 to talk about drugs. People of all ages approached me before and after readings to tell me about losing loved ones to overdose, and how anti-drug-user stigmas in the media impacted their lives. In the Q&A sessions, young people asked how to open up dialogue with elders who ascribe to prohibitionist mindsets. In one presentation I made for 11-to-13-year-olds at San Francisco Skate Club’s afterschool program, kids shared experiences of being stereotyped as a drug user because they are a skater (and wanted to know if you could be addicted to salty food—an excellent question, if you ask me.)

I had dreamed up #WEEDTOUR as a way to reintroduce my work in drug education to my home country. It turned into a moment in which I was doing the learning.

About the book, though: Weed is made of seventeen interviews with people from around the Western hemisphere—largely from Latin America, where I have lived for nearly the past decade, but also in the US, Canada, and the Caribbean. Individuals like Alejo Schroeter from Buenos Aires speak about being a medical marijuana patient. Mauro Melgar, a SoCal drug justice advocate, shares his experience being incarcerated as a teenager in an adult jail on cannabis charges. Nursing professor and renowned Canadian youth drug education specialist Emily Jenkins explains the concept of “spectrum of use,” and how kids can recognize when their relationship with any drug has become problematic. International connections abound. Readers meet a cannabis cook, a hemp architecture specialist, and even a music journalist who had to learn how to responsibly consume cannabis edibles. Their stories demonstrate that cannabis, that any drug, isn’t “good” or “bad”—that they only have the context given to them by us human beings.

On September 5th, after years of investigation and writing, months of tour planning, a pre-presentation at a national congress in Queretaro of Mexican cannabis women, and one last week in which my body staged a pre-journey COVID strike, Weed’s release date came. I jumped on a plane to Los Angeles and into my most intense, extended period of self-promotion ever.

It was the most stimulating month of my life. Dear authors, take your ideas on the road whenever possible!

What made #WEEDTOUR special was the diversity of the groups that showed up for youth drug education. In Los Angeles, my Hollywood friends like recording artists Fat Tony and Saturn Rising came through, alongside educators, and the crew of largely queer drug justice advocates of The Social Impact Center. In San Francisco, school drug ed innovator Rhana Hashemi interviewed me in front of a packed house of local journalists, nightlife event promoters, and my elementary school crush (hi, Dominic.) On my first trip to Vancouver ever, I presented in the hemisphere’s harm reduction capital with Students for Sensible Drug Policy—which along with its program Get Sensible provides some of the country’s most forward-thinking cannabis educational materials for young people, according to my co-presenter Emily Jenkins. That talk was followed by a touching and hilarious “open mic” for drug experiences, hosted by the SSDP.

I spoke to cannabis dispensary customers at a legacy (meaning it was around before Canada’s 2018 federal legalization) Vancouver weed store. The Portland Psychedelic Society hosted a conversation about talking to kids about drugs underneath the stained glass of a Presbyterian church. Small town gatherings provided some moments of levity: In the charming wooden stage of Tsunami Books in Eugene, Oregon a high-schooler said his middle school teacher “told us drugs were bad and if we did them, we’d die.” From the back of the room came a shout, “That’s not true!” Unbeknownst to the teen, his middle school teacher was also in the audience.

The one constant was that the book presentations were multi-generational. We left lots of time for crowd participation in the post-reading Q&As, and seeing 15 and 75-year-olds answering each other’s questions about how to communicate around psychoactive substances was everything I’d dreamed of when dreaming up the book.

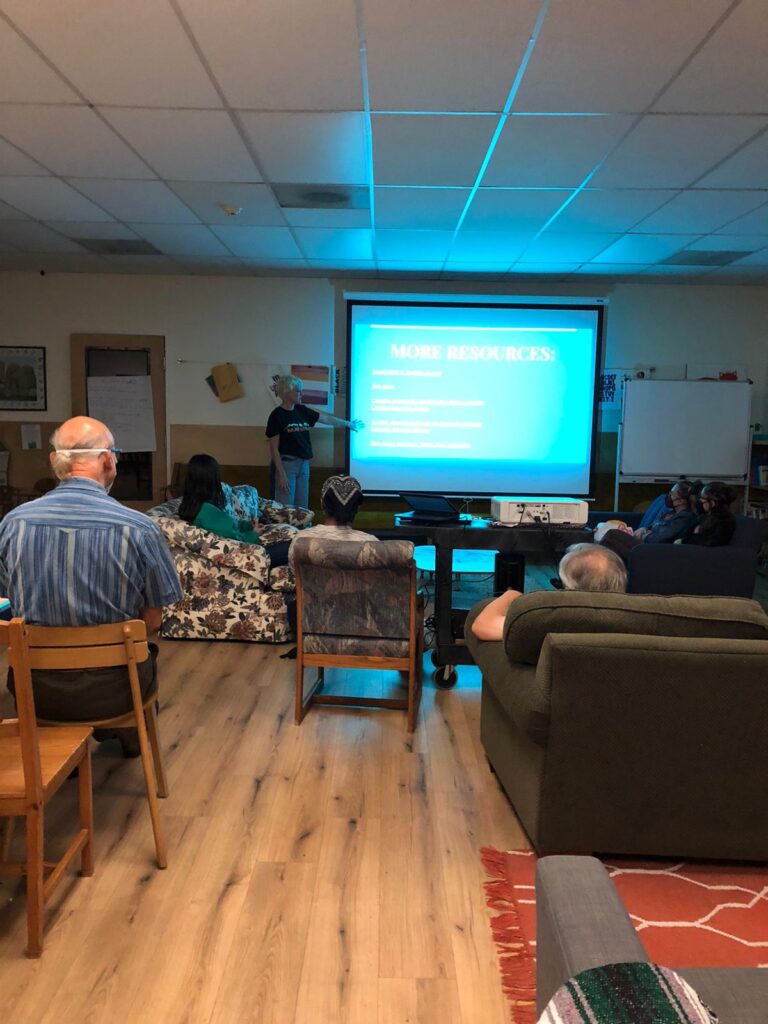

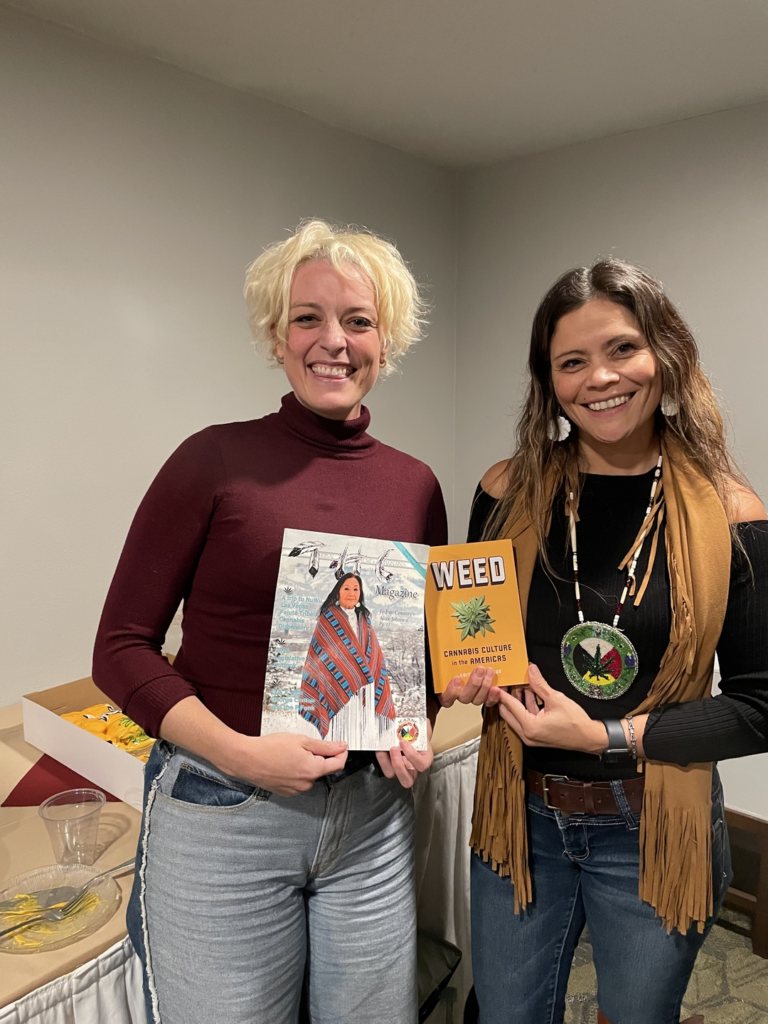

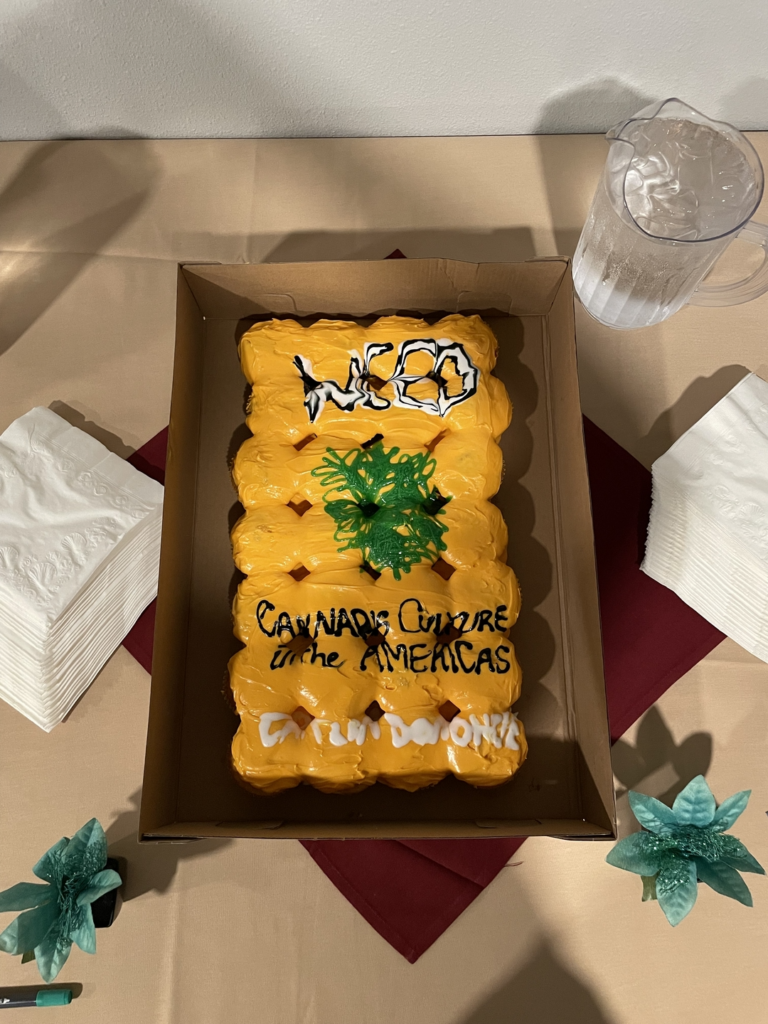

Some of #WEEDTOUR’s most special moments took place far off the beaten path of most book tours. Weed interviewee, Niimiipuu cannabis advocate, and founder of Tribal Hemp and Cannabis magazine Mary Jane Oatman invited me to present to her community on the Nez Perce reservation. The small event in a Holiday Inn conference room (complete with cupcakes frosted with the book’s cover design by Mary Jane herself!) drew tribal elders who were in the area to attend that morning’s water rights protest flotilla on the Snake River. Our ensuing conversation revolved around cannabis and tribal sovereignty rights, racially-biased on-reservation drug policing, and the politics of weed within First Nations communities.

I won’t soon forget what it was like to be a part of this talks against the backdrop of the US and Canada’s current overdose crisis. No matter where I went, I was reminded of those who we’ve lost to insufficient education around drug use, and deplorable lack of resources for individuals struggling with mental health and addiction issues.

School teachers provided me with other key moments of learning on #WEEDTOUR. My high school assistant basketball coach, still a health teacher at my alma mater in Portland, invited me to sit in while her sophomore class presented on self-care techniques. Privately, we talked about her student who had overdosed over the summer, about kids coming to school high. She so very much wanted to make a difference when it came to these young people’s relationship to drugs, but wasn’t convinced that harm-reduction-focused educational materials would sway kids from consuming.

Now, I’m convinced that nothing teachers say in a classroom will keep young people from doing drugs. But the care and anxiety she showed for these issues stuck with me, convincing me of the urgent necessity for administrators to take up a new kind of drug education like that which is advocated for in Weed. Other teachers told me that oftentimes, it’s actually parents who are uncomfortable with nearly any kind of drug education in the classroom. That’s to be expected, I guess: no one of child-bearing age today ever had drug ed worth a damn when they were in school, either. It’s going to take some bravery from everyone—young people, parents, school administrators, teachers, community members—to demand a new chapter when it comes to drug education.

Yesterday marked the return of Weed to the town that made the book possible, where it was imagined and written: Mexico City, where I’ve lived for the last near-decade. My co-presenter for the event was the amazing Lugo, a fluffy, yellow, button-eyed puppet who has spent the last decade sharing astute harm reduction videos on Youtube, and recently became the face of a drug education campaign for Mexico City’s UNAM, the hemisphere’s largest public university.

Again, we left a lot of time for crowd participation. A mom and daughter who sat in the front row talked about how beautiful their experience of mutual cannabis education had been for their mental health, and several people asked about challenges they’d experienced with their own marijuana use. There was a lot of prodding about why the book had not been made available in Spanish—a fair question, given that most of its interview took place in the language! I had the opportunity to talk about the United States’ special need for 1., internationally-focused perspectives of any kind and 2. harm reduction based, anti-prohibitionist drug education. I feel so blessed to be able to hear from people from all over the hemisphere about how the politics and culture of psychoactive substances impact them, and will continue to push for cross-border conversations of this kind.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I’d love to take the opportunity of being on this blog and in front of the eyes of some of my heroes, YA librarians, to ask for your feedback on drug education. What gaps do you see when it comes to the information that is available for teens around psychoactive substances? Where are the opportunities for such education in library and school settings, if any?

I look forward to hearing from you when you have the time. In case you haven’t already noticed, I love talking about drugs.

Meet the author

Caitlin Donohue is a San Francisco-raised, Mexico City-based bilingual culture journalist, radio producer, and drug educator. She’s written about cannabis culture and politics for 12 years, and Weed is her second book for young adults.

Author Links

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/caitlinbyrddonohue/

X/Twitter: https://twitter.com/caitlindonohue

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/byrdwatch/

Caitlin Donohue’s Website: http://www.donohue.work

About Weed: Cannabis Culture in the Americas

Humans have used cannabis for thousands of years, since Neolithic peoples sought out its medicinal benefits.

But for the past century, its use has been largely criminalized. Stigma around cannabis has made it difficult for people of all ages to get straightforward answers about how to minimize health risks related to cannabis consumption or to understand how the plant has shaped and continues to shape society today.

In Weed: Cannabis Culture in the Americas, culture writer Caitlin Donohue crafts a comprehensive and thought-provoking review of cannabis in the Western Hemisphere. Donohue’s investigation spans from Vancouver, Canada, to Buenos Aires, Argentina, interviewing medical researchers, educators, activists, artists, business leaders, and other experts to explore the long relationship between cannabis and the human race, its almost universal prohibition in the twentieth century, and modern efforts to legalize the much-maligned plant in all its forms.

ISBN-13: 9781728429540

Publisher: Lerner Publishing Group

Publication date: 09/05/2023

Age Range: 13+

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT