Intergenerational contact and queer YA, a guest post by Hal Schrieve

When a youth Speakers Bureau member came to my high school GSA in 2010 to promote a local support group which held meetings each Wednesday night, I cornered them after their talk: “You’re the first trans man I’ve ever met,” I breathlessly told them (they were not a man, but genderqueer). I remember the overwhelm and fear in their eyes at being a role model for a half-crazed freshman. I felt ecstatically drawn to them. I had only seen trans people online– I had come out alone, after watching videos and reading webcomics and Livejournal blogs, and while I had faith that some kind of future existed for me, it seemed impossibly distant. They were only 18, but anyone who had survived high school while trans seemed a rock star, an angel, and an adult. I negotiated with my parents: in exchange for wearing girl clothes when my grandmother visited, I got to go to the queer youth group this older teen had come to my school to represent. And I met more people, older than me, and older than them, who had been down the paths I was starting to traverse.

Instead of awkwardly sizing each other up from afar, clocking the ways we were uncomfortably similar and prone to similar harassment, and disavowing those deemed as cringey, as we did at school, at queer youth group we were all encouraged to reflexively confess our troubles to one another, and so gain an immediate, intimate connection. Kleptomania, parental homophobia, vampire fanfiction, unfortunate hookups, and struggles with bullying and self harm were all on the table, with the caveat that since the adults in the room were mandated reporters, we couldn’t actually talk about suicide or capital-a Abuse without it becoming known to some more remote authority. We still judged each other, and weren’t all friends, but in the moment, there was a culture of trying to offer some kind of genuine support. Sometimes, we met musicians and artists from our towns, like the members of G.L.O.S.S, or elders from the chapter of SAGE in Olympia. Other times, we were brought together to watch the classics that the grown-ups felt we shouldn’t miss: Paris is Burning, Hedwig and the Angry Inch, But I’m A Cheerleader, Better Than Chocolate, How To Survive a Plague. Some of the people who ran the youth group I went to had been in Act Up or had been teen runaways. They were trying to make sure we grew up safer than they did. One of the best things about the space was its library, donated by older gay men and women and with a few books I grew to treasure by Kate Bornstein, Susan Stryker, Leslie Feinberg and others. I regret to say I still own a copy of Hothead Paisan that I stole from my queer youth group.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Left to right: A photo of my friend Lucian from Stonewall Youth in Olympia Washington holding a picture of Miss Major at Pride, and SAGE Olympia parade float, circa 2015. Photo credit: Hal Schrieve

Then as now, queer adults were seen as suspect for wanting to be around queer kids. Many parents of kids who attended my group didn’t know that their teens were there, and would have been angry had they known. What kind of nefarious things were happening? The thing that homophobic and transphobic adults were afraid of is to some extent true: queer and trans adults want queer and trans kids to feel self-actualized and to express who they are and what they want in the world, and to be anything at all besides dead. Queer community is at once exactly what the right fears and also not: some queer and trans adults hope that they can encourage queer and trans kids to fight for the same causes they themselves have fought for, from abolition to harm reduction to decolonization. There are reasons to join these political movements, because queer youth are more likely to be homeless, substance-dependent, and incarcerated. At the same time, plenty of more conservative queer adults just hope that queer and trans kids can grow up to get married, not get HIV, and perhaps start a business or join the military. These kinds of youth support groups and nonprofits are not new, and have survived–now floundering, now thriving– across the English-speaking world for at least a couple generations, funded by sex-ed grants to prevent HIV or sometimes by community support. They happen in the context of AIDS decimating queer communities, and the subsequent life-or-death battle for LGBT sex education for young people. In the groups I was part of, we kept each other alive, and we made good– and sometimes very bad– art. I participated in Queer Rock Camp in Olympia, Washington, in 2014 and 2015, and while it was not perfect, it was deeply meaningful to be around so many adults who cared deeply about helping us play a few chords and sing sort of stupid songs about gender.

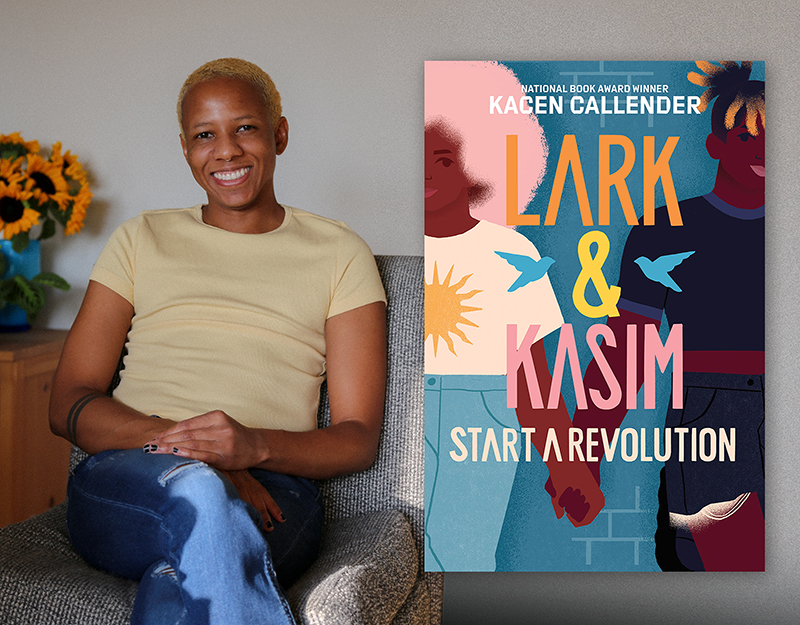

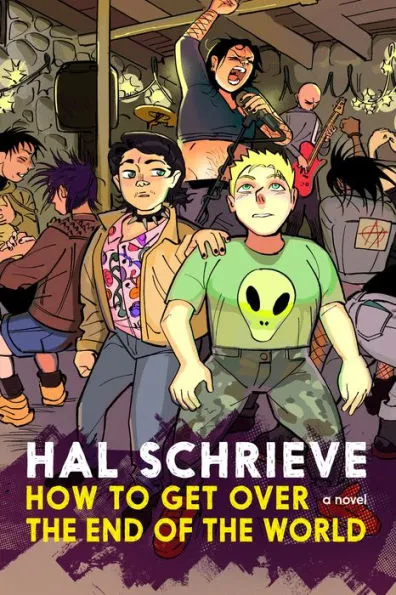

I get excited whenever I see complicated intergenerational queer existence reflected in books for young people. I felt motivated to write my own. In my novel How To Get Over the End of the World, my characters James, Orsino, Ian/Monique, and Opal face a dubious future for their youth group, just as they’re entering their last year of high school and starting a queercore band. When a show space burns down, Orsino and his sister’s girlfriend, local punk star Jukebox January experience strange visions promising that only they can avert a future filled with misery and death. The result, for better or worse, is that everyone chaotically gets involved in staging a rock opera to save the youth group. The main characters don’t spend a lot of time vocally appreciating their queer youth group, finding it insufficient, unsatisfying, full of well-meaning people who don’t really understand them– but at the same time, as it was for me, it’s the center of their social world. It provides stipends to James and Opal for doing queer youth workshops, and even if older teens no longer get exactly what they need from its support groups, they feel called to show up for it as it struggles for funding. Adults rally to ensure that the rock opera gala the youth devise to raise money for their group has resources, and the cool, punk queer people around them want to be involved. The world is bigger than just that space– but at the same time, it isn’t. If that space ended, the world they live in would disappear too.

Youth can’t make it through their teens alone. Ultimately, the adults were who I came to see at my youth group. A collection of mid-twenties to mid-thirties punks and adjacent artists who had partially or completely made the transition to nonprofit work, they offered what insights they could to us about navigating our lives and claiming the identities, clothes, literary traditions, art, or communities we were missing. As formal support group facilitators, they allowed each of us to talk, offered us thoughts and resources. As programmers, they offered us movie nights and crafts, social justice seminars and dances, and–partly in order to access government grants– also provided sex education workshops about how to avoid and treat STIs, navigate consent, and what hotlines to call. They tried to have good boundaries– or, I don’t know, some of them did. When they didn’t, we learned more about who to trust and who not to. We asked them for help in the formal capacities allowed by their jobs at the youth nonprofit; I know that we also often needed different help from them, both intangible and material. We wanted tarot card readings, invitations to shows; others needed housing, car rides, clothes. We got some of these needs met, though I watched adults struggle with their responsibilities toward us. The nonprofit needed to protect its grant funding.

In my college town with a robust if scrappy DIY scene, I would never have known about abolition, imperialism, the history of AIDS and gay liberation, or my city’s recent past as the pinnacle of Riot Grrl without the people ten to thirty years older than me who turned their attention to us, their critical, naive, creative, despairing, hopeful heirs.

Some novels for young people about intergenerational queer community that I find valuable:

In Sasha Masha by Agnes Borinsky, the isolated transfeminine central character begins to realize who she is in relation to others after seeing Querelle at a queer youth center with a straight girl she’s trying to date. Her contact with two older drag artists and their idols shores up her own sense of self.

Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me by Mariko Tamaki and Rosemary Valero-O’Connell focuses on a teen lesbian couple with a massively dysfunctional dynamic: Freddie’s queer peers, but also her older acquaintances and coworkers, help her see that her girlfriend isn’t the whole world, and doesn’t value her like she should.

Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars by Kai Cheng Thom both is and isn’t a YA novel– but it is short, vivid, and striking. It’s about a teenage trans girl who runs away from home and finds an imperfect community in nonprofit spaces and bash-back street gangs. Full of magic and misadventure, it’s one of the only books that speaks to a very common experience of literal disownment, too brutal for many more school-library-friendly books to address, but with an earnest, loving heart.

Across A Field of Starlight by Blue Delliquanti features a revolutionary army who employs child soldiers to battle an empire, a pacifist space commune, conscious AI, and a trans mentor who is much less than perfect but still gets a kid their first binder. Operatic in scale, with a queer teen pen-pal-ship for the ages.

In Love and Other Curses by Michael Thomas Ford, a small town’s drag scene is a safe space for a gender-nonconforming gay boy– and though his teen trans boy love interest is written as one-dimensional and angry (a common thread I see in cis perceptions of us), I appreciated that it recognizes that trans teens can be appealing to their peers, and found much that was familiar in Ford’s descriptions of long drives through rural areas to reach the places where we can find medical care and social connection.

Felix Ever After by Kacen Callendar, about a Black queer teen trans boy, doesn’t have many queer adults interfere with the catastrophically messy central youth, but Callendar does include a moment where Felix is exposed to the concept of a demiboy at a queer youth group when it’s mentioned by an older mentor. The youths’ conversations about whether being a trans man is inherently sexist, whether astrology is real, and whether art should be moral ring fundamentally true for me.

The Stars and the Blackness Between Them by Junauda Petrus is about two Black queer girls, Mabel from Minneapolis and Audre, displaced from Trinidad after being disowned by her mother. They navigate love, hope, justice and illness together. A penpal-ship with an older queer inmate whose book has spoken to Mabel in a time of crisis is central to the story’s development, and Petrus makes clear that our liberation is all connected.

Juliet Takes A Breath by Gabby Rivera– Puerto Rican gay Juliet, who is slowly being ghosted by her girlfriend, also discovers that her lesbian-feminist author idol is a lackadaisical, mercurial stoner whose haughtiness disguises unexamined racism. Juliet finds solace in more diverse queer communities in Florida, while also finding the courage to call in the woman she once idolized. I love this book: it has great plot beats, realistic details, and a loving, nuanced portrait of the ways we can grow together, even painfully.

Kyle Lukoff’s middle-grade novels also engage with these questions, though for a younger audience. In the Newbery-winning Too Bright To See, tween Bug’s sense of self-worth and identity has always been supported by his uncle Roderick, a drag queen, and while Roderick passes before Bug comes out as trans, his ghost continues to speak to Bug and helps him find information on what his life could look like as an adult.

Lukoff’s Different Kinds of Fruit attempts to tackle an even thornier issue, one which made me very nervous on first reading: a trans father, living as stealth, whose experience with intra-community exclusion has driven him to live isolated from other queer people, and whose internal transphobia expresses itself towards his daughter’s nonbinary friend. I got scared, reading this, because, I guess, I didn’t want young people to see older trans people as this backward, this damaged. But the truth is, every generation gets traumatized, and carries forward that baggage.

Other books I recommend young trans and queer people read, though they are not marketed to teens:

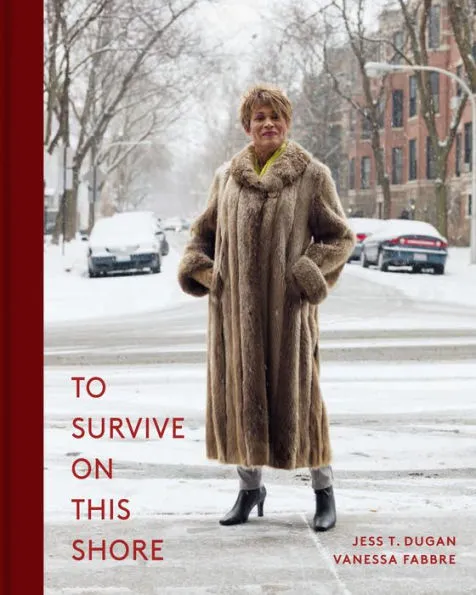

To Survive on This Shore: Photographs and Interviews with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Older Adults b Jess T Dugan and Vanessa Fabre .

If you have a feeling that there is no future for you, there is. It’s here. That’s what you might look like. Here’s who you might be, with a love’s arms wrapped around you. These are portraits of older trans people (50+), and every time I read it I am filled with hope and with gratitude for those who came before.

Transgender Warriors by Leslie Feinberg

Feinberg was among a wave of activists in the 1990s who advocated for a collective transgender identity, not fractured, standing in solidarity for the right to exist in public, access healthcare and housing, and be who we are. This history is an early perspective on the history of trans people, and while as a history it has a few things to critique (white trans activists like to link our struggles to decolonial ones, and I don’t think such a link is automatic), it also is radical, informative, and visionary.

Hello Cruel World: 101 Alternatives to Suicide for Teens, Freaks and Other Outlaws by Kate Bornstein

This book, with many ideas of what to do if you are stuck, trapped, or hurting, ranked in terms of easiness, danger, and sustainability, comes from someone who survived and escaped a cult and led a wild, artistic life. It’s eminently useful. I am not sure if it saved my life, but it gave me a framework for harm reduction.

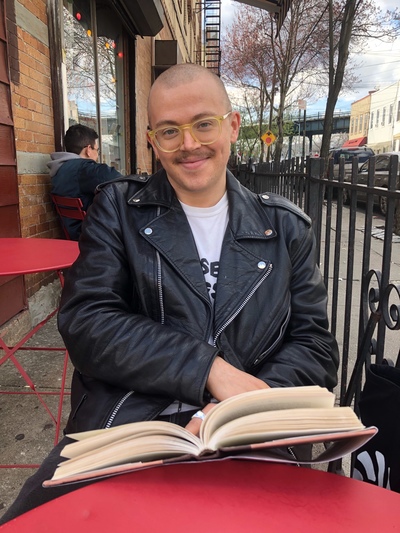

Meet the author

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

HAL SCHRIEVE is a children’s librarian in Manhattan and the best part of hir job is facilitating comics and creative writing workshops with young people. Hir first book, Out of Salem, was longlisted for the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. Hal’s comics are featured in We’re Still Here, an all-trans comics anthology, and the zine Very Online. Hal’s comic Vivian’s Ghost was on the shortlist for Comics Beat’s 2023 Cartoonist Studio Prize Award for Best Webcomic. Follow Hal at @howlmarin on Instagram and @hal_schrieve on Twitter.

About How to Get over the End of the World

Boldly weird, cool, and confident, this YA novel of LGBTQ+ teen artists, activists, and telepathic visionaries offers hope against climate and community destruction. From the National Book Award–longlisted author of Out of Salem.

James Goldberg, self-described neurotic goth gay transsexual stoner, is a senior in high school, and fully over it. He mostly ignores his classes at Cow Pie High, instead focusing on fundraising for the near-bankrupt local LGBTQ+ youth support group, Compton House, and attending punk shows with his friend-crush Ian and best friend Opal. But when James falls in love with Orsino, a homeschooled trans boy with telepathic powers and visions of the future, he wonders if the scope of what he believes possible is too small. Orsino, meanwhile, hopes that in James he has finally found someone who will be able to share the apocalyptic visions he has had to keep to himself, and better understand the powers they hold.

How to Get over the End of the World confirms Hal Schrieve as a unique and to-be-celebrated voice in LGBTQ+ YA fiction with this multi-voiced story about flawed people trying their hardest to make a better world, about the beauty and craziness of hope, about too-big dreams and reality checks, and about the ways in which human messiness—egos, jealousy, insecurity—and good faith can coexist. It also about preserving the ties within a chosen family—and maybe saving the world—through love, art, and acts of resistance.

ISBN-13: 9781644213018

Publisher: Seven Stories Press

Publication date: 10/10/2023

Age Range: 13 – 17 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT