The Pain of Invisibility, a guest post by Carmen Tafolla

Too many children in today’s world become invisible when they begin their formal education. Some lose their name or their language. Some find their culture, history, or any evidence of their existence erased. Some may even lose their voice, and feel almost completely invisible.

Warrior Girl is about a young Mexican-American, who in her first 7 years of formal schooling, had her name changed, her language forbidden, and her cultural history erased and distorted. But it’s also about a young girl who, after years of moving from small town to small town while her father followed the job market trying to support his family, re-locates with her parents to a large multicultural town to live with her Gramma, and starts seventh grade determined to lead life on her own terms. But just as she’s set her sights on reclaiming her name and her pride in her heritage, her father gets deported back to Mexico, and the news erupts with stories of cages being built at the border to lock up undocumented people; videos of violence from racial injustices; rising anti-Mexican sentiments; and a pandemic!

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

This book is about reclaiming what is yours, reclaiming those lost parts of yourself, whose absence still hurts, and reclaiming them in a way that reminds you that there is joy and celebration and a spirit in your core that can never be lost. Or as Celina Teresa Guerrera Amaya puts it:

Because when you’re celebrating,

when you find a reason to be happy,

a reason to sing or dance or paint

or play or laugh or write,

they haven’t taken everything

away from you.

This book is also about stress – and survival – and strategies for how to deal with big problems in ways that effect change, but that also bond you closer to others. It’s about the shield that each of us has to learn to build, a shield that lets some things through, like smiles and friendship, hope, and the joy of new adventures, but makes other things— like dirty looks or sneers or lies and insults— just bounce off that shield and never penetrate your inner core.

Our young sheroe discovers some surprising strengths and wisdom in her Gramma, and also in herself; gains courage from three friends who join her in her commitment to social justice; and blossoms under the encouragement of several teachers who not only see her and make her visible, encouraging her love of writing, but also respect her piercing questions, and dialogue with her to find answers.

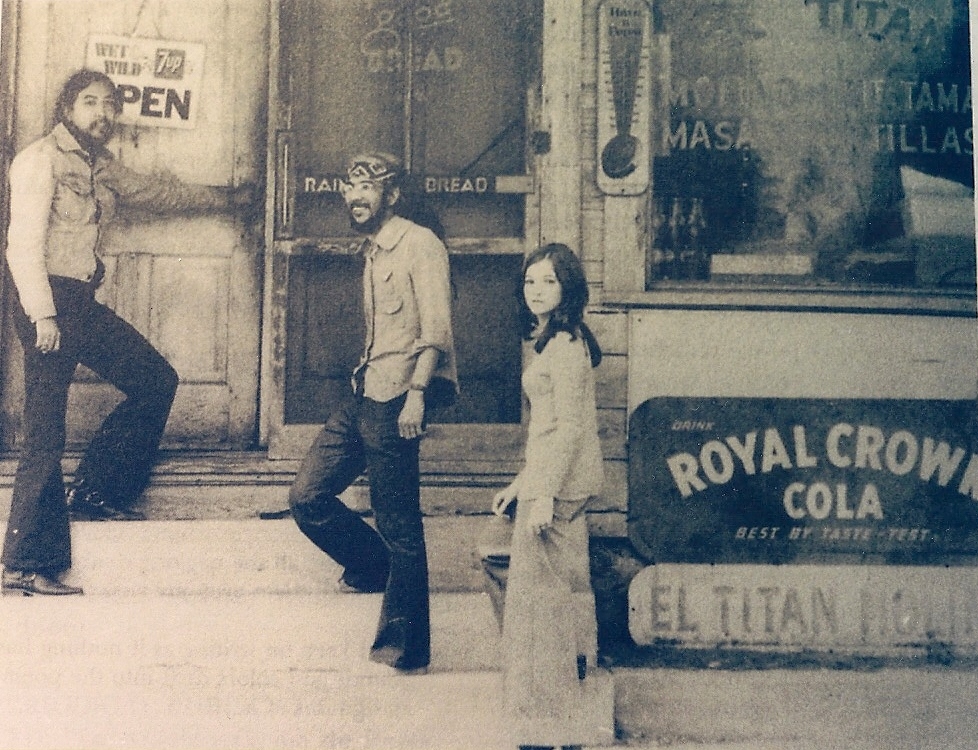

cover foto of my first book, a collection of poetry co-authored by Reyes Cardenas,

Cecilio Garcia-Camarillo, and Carmen Tafolla (Get Your Tortillas Together,Rifan Press, 1976.)

But this young sheroe is no superhuman fictional character with special powers. She represents so many children who have become invisible in settings that ignore their existence and their potential, and deny them books that reflect their own experiences and histories. In this very moment, as you read this article, there are states passing laws that ban the mention of the very experiences that children are grappling to understand in their own families’ lives. There are school districts and politically motivated action groups organizing to rewrite history books to erase what little recognition and mention diverse populations of color have gained.

There are school districts, under the new management of state boards, turning school libraries into detention centers. There are children like Celina Teresa Guerrera Amaya who are being erased from the very history books that are supposed to be educating, nourishing, and empowering them to be our future leaders.

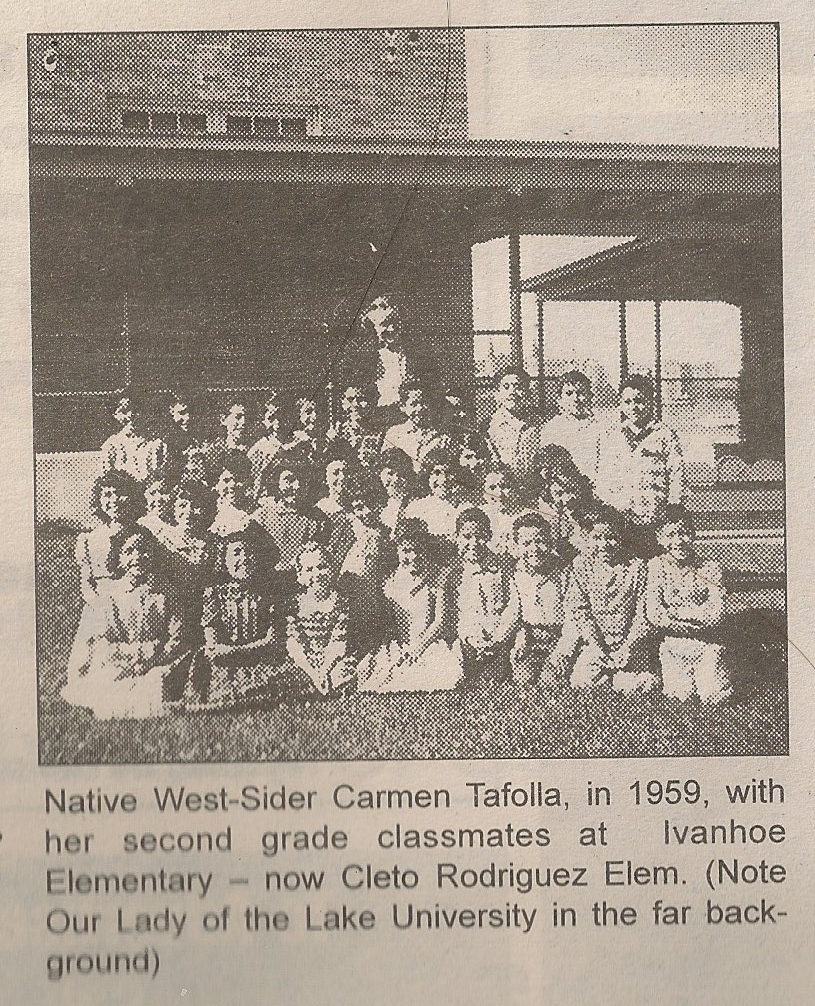

Readers of all ages have asked me, where did Tere come from? And to be historically precise, I admit that this particular child, the young, first-grade Tere that Celina Teresa recalls in the book, was born on stage, as part of my one-woman show, in 1990. Most of the stage characters I presented were dramatizations of characters already in my poems and stories, but Tere was a story that needed to be told, whose voice was needed , so I added her to the performance, even though she had not previously appeared in my print stories and poems. The one-woman show, With Our Very Own Names, traveled the world to standing ovations. The character Tere was also Featured on Latino USA w Maria Hinojosa. (The link to this interview appears on my website, www.carmentafolla.net). But to be completely open, this character began long before 1990 — it was a story engraved on my soul. It was the story of generations of children in my state, children of Mexican descent , who arrived at school with two languages and two cultures, but had one of those languages drilled out of them and even (for more than 50 years) outlawed by state law, and one of those two cultures demeaned and denigrated within the very schools that were supposed to be educating them. It is one of the most important reasons why, for decades, huge percentages of Mexican-Americans dropped out of school to defend their own sense of self-worth , or more accurately, were “pushed out” in their struggle to NOT be invisible, and NOT be painted as the enemy. It was, and still is, a deep scar in the 175-year history of Mexican-American culture in the United States.

In the book Warrior Girl, Celina Teresa writes “First Grade Tere tells her story” as a memory, one that still stings in her own realization that she has been silenced. To a child like Tere, centered on making our world more fair, these levels of racism and eurocentrism scream out as contradictory to everything we’re taught to believe as a democracy. But Tere is an echo of the childhoods of many people of color in the 1920s, 30’s, 40’s,50s, 60s, 70s, 80s, 90s, and which is still happening today with only small variations. Children are being made to feel excluded and erased in their books and curriculum, devalued because of their names, their language, their countries of origin, their clothing, even their very skin color. When a more confident and mature 12-year-old Celina Teresa Guerrera encounters a blatant colorism in her own school day (witnessed in the poems “Erased & Ignored”, “CleanCut” & “Don’t Let it In”) she has to find ways to maintain her own values and non-violence while surviving the system in which she must succeed.

Celina Guerrera calls out ethnocentrism, and opens our minds to the possibilities of new calendars, new heroes, and new perspectives on history and what constitutes a civilization. She does this while trying to live her life in celebration, joy, and all the richness of a life lived with pride in who you are.

Warrior Girl also improves our sanity and sense of peace in the midst of crisis, by providing us extra sources of strength and connectedness, and speaks to ageism by providing counternarrative. Gramma is strong, significant, radical, and the more we get to know her, the more, like Celina Teresa, we see that Gramma is part of history and has helped change the world. Not only is this a counternarrative to the usual modern view of “boomers” as out-of-touch and incompetent, but Gramma is also a crucial part of Celina’s learning the survival strategies that don’t merely resist the negative messages, they BUILD on positive experiences, and a philosophy of celebrating at every chance. Gramma also reflects the segment of the Mexican-American population that is native born and fully patriotic citizens, but also fully engaged in defending their identities as indigenous people, with all the values of peace, tolerance and a collaborative route to consensus that created the INDIGENOUS bases of our dual democratic bodies of congress for the U.S.

Warrior Girl makes visible what has for centuries of schoolbooks been treated as invisible. It puts a face on the image much of this country has about what an “illegal immigrant” is, and sheds light on the many families who have citizen and non-citizen members, and who incorporate two cultures and two nations into their identity and daily lives. It describes some of the injustices and inconsistencies in our treatment of the undocumented, as well as our biases against Mexican-Americans as “foreigners”, when in reality their indigenous roots make them more native than European-origin populations.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

But I believe the most important message in Warrior Girl is about the universal human hunger to be seen and appreciated. To be heard, not silenced. To know one’s history, and to be able to share it in a context where others, too, are given a chance to know and share their histories. This is what good broad-range libraries do. They let us hear our own stories and our own dreams, the stories and dreams of others too, and result in a diverse but bonded community that can jointly celebrate all that has NOT been taken away from us. This, to me, is something worth fighting for, worth being, as is Celina Teresa Guerrera Amaya, worthy of our name, as Guerreras and Guerreros, (Female Warriors and Male Warriors), who fight for justice and joy for everyone.

Meet the author

Dr. Carmen Tafolla (carmentafolla.net) is the 2015 State Poet Laureate of Texas and the former president of the TexasInstitute of Letters. An award-winning poet and children’s author, storyteller, performance artist, motivational speaker, scholar, and university professor, she is the author of more than forty books and a professor emeritus of Transformative Children’s Literature at UT San Antonio. Her numerous awards and distinctions include the prestigious Américas Award, the designation of first city Poet Laureate of San Antonio, six International Latino Book Awards, two Tomás Rivera Book Awards, two ALA Notable Books, the Art of Peace Award, and the Charlotte Zolotow Award. She lives in San Antonio, Texas.

About Warrior Girl

An insightful novel in verse about the joys and struggles of a Chicana girl who is a warrior for her name, her history, and her right to choose what she celebrates in life.

Celina and her family are bilingual and follow both Mexican and American traditions. Celina revels in her Mexican heritage, but once she starts school it feels like the world wants her to erase that part of her identity. Fortunately, she’s got an army of family and three fabulous new friends behind her to fight the ignorance. But it’s her Gramma who’s her biggest inspiration, encouraging Celina to build a shield of joy around herself. Because when you’re celebrating, when you find a reason to sing or dance or paint or play or laugh or write, they haven’t taken everything away from you. Of course, it’s not possible to stay in celebration mode when things get dire—like when her dad’s deported and a pandemic hits—but if there is anything Celina’s sure of, it’s that she’ll always live up to her last name: Guerrera—woman warrior—and that she will use her voice and writing talents to make the world a more beautiful place where all cultures are celebrated.

ISBN-13: 9780593354711

Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

Publication date: 09/05/2023

Age Range: 10 – 12 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Endangered Series #30: Nancy Drew

Research and Wishes: A Q&A with Nedda Lewers About Daughters of the Lamp

Review| Agents of S.U.I.T. 2

ADVERTISEMENT