Gateway to Literature, a guest post by Marina Budhos

It was our first day of performing at a high school, and we—me, an author, four actors and a director– were pacing a black box theater. Who would run the lights? Were students coming? In the halls, I heard confusion about whether teachers would even release their students. Testing, we were told, tensions between faculty and the administration.

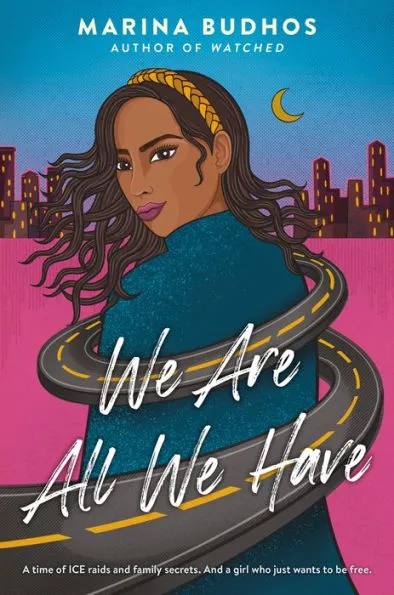

This was the first of several performances, a program created by me, the author of the YA novel We Are All We Have, Ari Laura Kreith, Executive Director of Luna Stage, and AAPI Montclair for Asian American Pacific Islanders Heritage Month. Set in 2019, We Are All We Have tells the story of Rania, a Pakistani teenager, whose life is upended when her mother, an asylum seeker, is swept up in an ICE raid. Kreith and I had previously collaborated on my YA novel Watched, and we wanted to bring this form right into schools, where students could be exposed to the story, and the complex themes of immigration, freedom, sanctuary, and first love. We had booked a very tight schedule—three days, chock full of performances, in seven schools in Maplewood, Montclair, and Glen Ridge, NJ.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

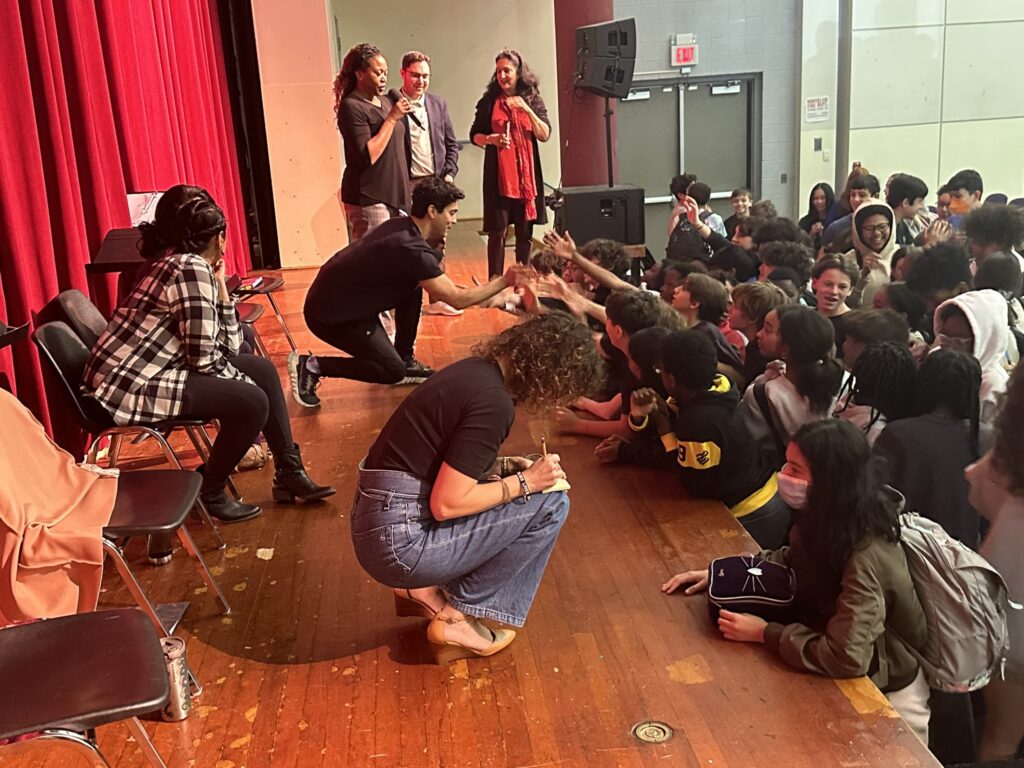

Soon a small group of students began to trickle into the theater–all from an AP Literature class. The four actors took their places, opened their script binders, and led the audience in vibrant enactment of six scenes from the book—a teaser from the first parts of the narrative. After, we embarked on a rich and fascinating talk back, all of us sharing perspectives on the story itself. We did it again—for a full house of high schoolers, who brought their own sets of questions.

This was the core of the program: that literature can be brought to life through the performances of professional actors. The world of my characters—a teenage girl bursting with life, a fierce poet about to graduate, ready to take on the world, yet forced to navigate a baffling immigration system and family secrets. Our adaptations were always based on the language in my book, though sculpted for performance. Sometimes lines were cut for pacing, or material from other parts of the novel was woven in to help establish its world. Thus, the students were truly experiencing these performances as prose and literature.

Lipica Shah brilliantly evoked Rania’s fieriness, confusion and hurt, in a narrative passage turned into a monologue. She also portrayed the heartbreak of seeing a mother behind bars in a detention center. Their performances of We Are All We Have brought home searing issues that are all around us without lecturing: the vulnerability of some young immigrants, perhaps the same age as these students. What it means to fear deportation or ICE raids, or simply, losing your mother and having to be an adult to your kid brother. What it means to flirt with a boy in a shelter, who has his own story of flight and fear, too.

There were glitches and lessons to be learned: at one performance, actors had to compete with slamming doors as kids went to the bathroom and staff made kitchen noises to prepare for lunch. Then came the afternoon when we showed up to the wrong building, marched down the block to the auditorium, only to learn that our audience was not high school students, as expected, but an entire middle school crammed to the auditorium rafters. Backstage, we frantically regrouped and decided to shed a scene to make the program more accessible to those ages.

For all the mishaps and anxiety, the experience was exhilarating. The assemblies were electric. Students remained riveted through the performances, hands popping up after, clamoring to be called upon. Given that the student groups skewed younger than we expected, the actors—professional, flexible–came up with a way to ground the students in the book’s sometimes sophisticated immigration context. Instead of my usual author introduction, each actor opened with reading a short definition of words students would encounter—asylum, detention, undocumented, ICE. They made it funny—“For ICE, we don’t mean what you put in a drink to make it cold, or a lot of jewelry.” We learned to direct the discussion, which sometimes focused too much on what-happens-next plot mechanics, steering them toward the deeper themes of the novel and how they might get involved on these issues in their own communities.

For me, seeing my very own words and scenes performed by gifted artists, was mesmerizing and moving. But it also reminded me of how isolated young people have been in these past few years, in the wake of COVID. Reading levels have dipped; students attention spans have been shattered. Readers Theater is a way to get young people to connect to literature and to feel connected; to see that the world of fiction, of reading, can be alive and exciting—can be embodied in live performers who themselves had stories to tell, a message to convey. The actors spoke touchingly of their own journeys as actors of color, immigrants, and how they came t theater. The very aliveness of the program made many students recognize the power of the word, piercing through the numbing digital ether we all live in.

While Readers Theater is an exciting possibility for our schools, it can be logistically challenging. I gave up my fee so the actors could be paid as professional working artists, and funds could be used for rehearsals and development. Schools are often stretched thin administratively, so it helps to appoint a tour manager to sort out book sales, contacts, venue requirements. I also made sure to have curriculum guides for middle and high school, so if the teachers want to further pursue this novel and its topics, they had resources readily available. It’s also important to clarify who the audiences will be: six hundred middle schoolers who swooned when they learned one of the actors once played a Power Ranger? Or a tiny group of AP literature students who leaned in intently and engaged on a high, challenging level?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

One of the more smartly organized programs was two-part: an all-school performance followed by my visit with a small group of motivated students who had already read the novel; a social studies teacher had already led several in depth discussions during the month. I could also imagine all kinds of other possibilities: smaller theater workshops with actors where students get to embody the scenes and discuss afterward; writing workshops where kids try their hand at adaptation and writing for stage.

At a moment when librarians and schools are seeking to re-engage students in a love of reading, Readers Theaters can be a gateway to literature, opening up empathy, critical thinking, and cultural learning. It brings us back to what matters—stories and the lives of young people, just like them. It shows them that books can be live, too.

Meet the author

Marina Budhos is the author of several books for young adults and adults. Her newest novel, We Are All We Have, was a Best Kirkus Book of 2022. Among her prior books are Watched, which received a Walter Award and an Asian Pacific American Honor, The Long Ride, Tell Us We’re Home, and Ask Me No Questions, recipient of numerous honors. She has also published the adult novels The Professor of Light and House of Waiting, and three works of nonfiction, including Sugar Changed the World, an LA Times Book Finalist. She has received an NEA Literature Fellowship, a Rona Jaffe Award for Women Writers, three Fellowships from the New Jersey Council on the Arts, and has been a Fulbright Scholar to India. She is a professor emerita at William Paterson University. You can find out more at her website here.

@mbudhos

About We Are All We Have

When a teenage girl’s single mom is taken by ICE, everything changes—all of her hopes and dreams for the future have turned into survival.

Seventeen-year-old Rania is shaken awake in her family’s apartment in Brooklyn. ICE is at the door, taking her mother away. But Ammi has done everything right, hasn’t she? Their asylum case is fine.

This was supposed to be Rania’s greatest summer: hanging out with her best friend, Fatima, and getting ready for college in the fall.

But it’s 2019, and nothing is certain.

Now, along with her younger brother, Kamal, and a new friend, Carlos, Rania must figure out how to survive. A road trip leads to searching for answers to questions she didn’t even think to ask.

In this vivid exploration of what happens when the country you have put your hopes into is fast shutting down, award-winning author Marina Budhos shows us how one girl bursting with dreams navigates secrets, love, and the lure of the open road.

ISBN-13: 9780593120200

Publisher: Random House Children’s Books

Publication date: 10/25/2022

Age Range: 12 – 17 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on BlueSky at @amandamacgregor.bsky.social.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Should I make it holographic? Let’s make it holographic: a JUST ONE WAVE preorder gift for you

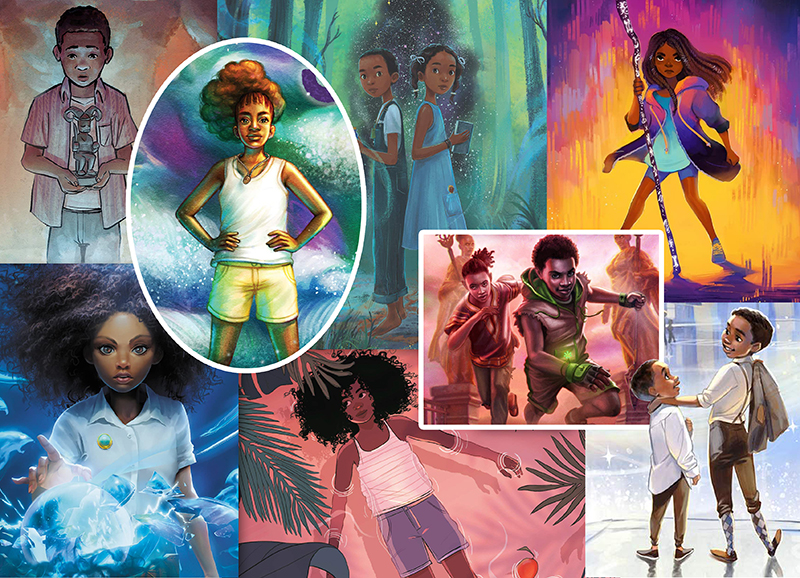

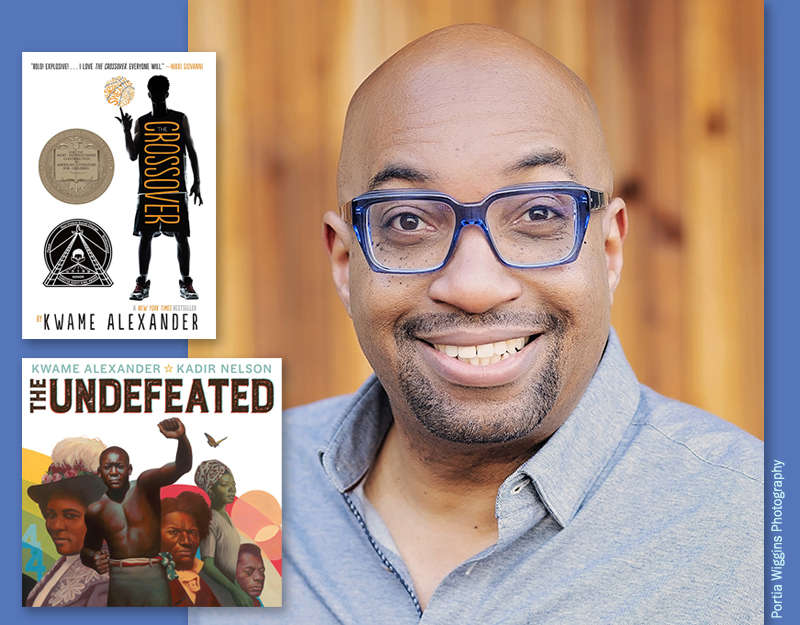

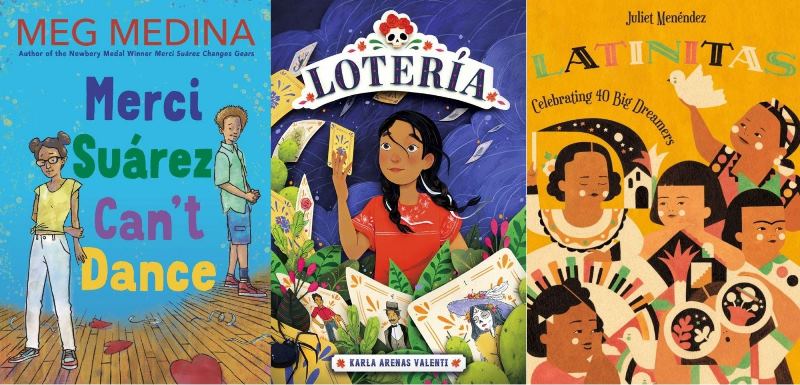

Press Release Fun: Happy Inaugural We Need Diverse Books Day!

Halfway There: A Graphic Memoir of Self Discovery | Review

Fifteen early Mock Newbery 2026 Contenders

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

ADVERTISEMENT