The Parentified Protagonist: From Shifting Roles to Shapeshifter, a guest post by Stephanie Willing

My mother made me her emotional confidante after I broke down watching the movie, COMA. I was almost thirteen years old, and when she saw me in tears about fictional people who’d had their organs harvested, she somehow surmised that it was time for me to know about her childhood abuse. My tears dried as she shared trauma after trauma, and I felt my purpose harden. I would help my mother and keep her happy.

Photo by Michael Willing.

I was her firstborn, and she always said that she wished she could’ve had me as a best friend when she was younger. Eventually I was the eldest of four kids, and my entire personality became the praise “she’s so smart,” or “she’s so responsible.” I soothed my mother when her feelings would overwhelm her, and I’d watch my younger siblings so she could have time for herself.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Right before this change in our relationship, my parents had chosen to homeschool all of us. At the same time, my parents decided we’d be an “immediate obedience” family, where talking back, arguing, or even a look of disagreement was punishable. I had no power, and yet I felt completely responsible for my mother’s mental state. If she was sad, I was sure I’d messed up somehow. If she was happy, so was I, and everything was right with the world.

According to Wikipedia, “parentification or parent-child role reversal is the process of role reversal whereby a child or adolescent is obliged to act as parent to their own parent or sibling.” Additionally, there are two distinct kinds of parentification: instrumental and emotional. Instrumental parentification is when a child takes on the daily tasks of life such as cooking, cleaning, paying bills, and caring for siblings. Emotional parentification is when a child provides emotional support to a parent as a mediator or confidante.

The word parentification is everywhere right now (or maybe it’s just all over my TikTok algorithm, which is telling). But while it’s obvious to me now as an adult that my mother initiated an unhealthy parent-child relationship, I had no concept of parentification back when I was twelve going on thirteen.

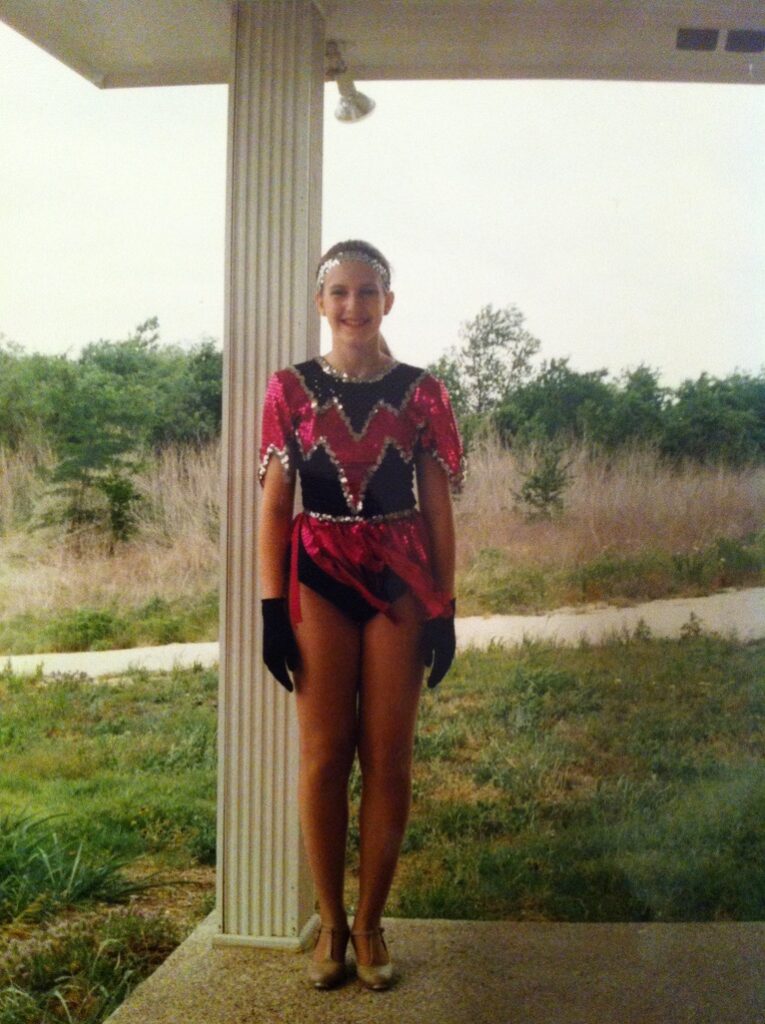

Photo by the author.

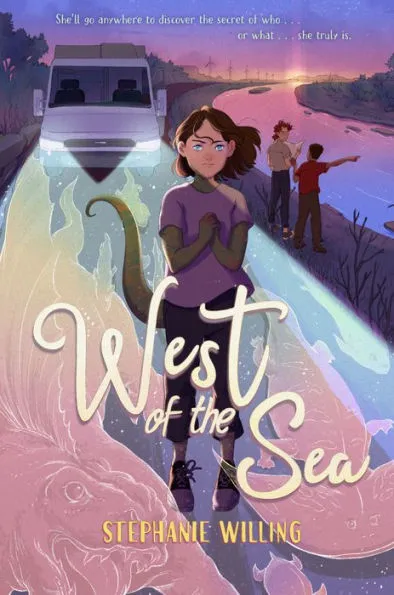

In WEST OF THE SEA, the point of view character is 12-year-old Haven West. However, it’s her older sister Margie who experiences the most oppressive blurring and bending of parent-child roles in the story. Haven and Margie’s mother, Maureen, has been deeply depressed has taken on a lot of the practical care of the household. Margie plans and cooks the meals, does laundry, watches out for Haven, and tries to coax her mother to eat.

Haven, on the other hand, monitors her mother’s body language and moods. She keeps a smile on her face and hides her true feelings to keep her mother as steady as possible. In another parent-child role reversal, she is trying to help regulate a dysregulated parent. While Haven has her big sister to lean on for the necessities of daily life, she’s doing a lot of emotional work trying to care for her mentally ill parent.

When I wrote this fantastical story about a mentally ill mother (who is also a shape-shifting cryptid) who disappears in the middle of the night, I knew I was writing my own internalized mythology. How many times did I wish there was a magical reason my mother was the way she was? That if I could just shapeshift to be what she needed, I could pull her back from the edge?

My mother and I were very close until I went to college and began to make choices she didn’t like. Once I was no longer the obedient daughter, she didn’t trust me. Our phone calls became guarded–I never knew if she’d answer the phone at all. Visits home became more and more strained. She never visited me in New York. She didn’t come to my wedding. She has never met her grandchildren. At this point, we are completely estranged, by her choice, and it is absolutely heartbreaking.

I say that, and yet, now that I’m nearly forty, being unmothered feels like nothing. The unmothered existence is a chilly body of water that I am numb to, and I don’t think about it too much because if I do, I will slip under the surface, and I am too busy with my own life and children to spend time there.

Photo by the author.

I only feel the bone deep ache of it when I bump into the alternative. The incidents are always tiny, which makes sense, since parenting is made up of a thousand small moments a day.

The trigger could be the older woman on a blustery day who frowns as she wraps a scarf around her adult, pregnant daughter’s neck. Or it’s the lookalike mother-daughter tourists in NYC waiting in line for the Stardust Diner, tired and out of place and excited, and who no doubt have dinner plans and Broadway tickets for that night. It’s another mom friend casually mentioning that her mother is coming to stay with her so she doesn’t have to solo parent while her husband travels for work.

Alone. It feels melodramatic to type that out, but that’s what that moment feels like. You are alone. You weren’t a good enough daughter.

When I found a battered copy of Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time at a thrift store in Fort Worth, I had no idea it would change my life. I read it in the way-back of our old Volvo on the 45-minute ride to our home in Cleburne.

I clung to that book for a million reasons, but the thing that is so obvious now is that this was the first time I’d seen that it was okay to be angry. Meg Murray is furious! And yes, it’s love, and her parentified-sibling bond to Charles Wallace that saves the day, but it’s also that deep fury and stubbornness and innate, imperfect pre-teen-ness that makes it possible for her to outwit IT.

I needed to know it was okay to be angry, and that my “flaws” were also my strengths. In contrast to my own life, Margie in West of the Sea knows that her home situation is messed up. She is under no illusions that her mother’s actions are harming their family, and she’s angry and loud about it. She is protecting her heart because anger isn’t just a force to be reckoned with. It’s a boundary.

I hope West of the Sea will find kids who are taking on a world of responsibility and help them recognize that their parents’ dysfunctions are not their fault. I also hope they realize much earlier than I did that it’s not in their power to “fix” an adult, no matter how much we want to save the people we love from their struggles.

Photo by the author.

As my mother’s child, I’m in therapy for obsessive anxiety caused by the parentified belief that if I can somehow make all the “right” choices I can keep my children safe and happy.

But as a mother myself, I’m practicing how to be honest about my feelings without making those feelings my children’s responsibility. It’s all in the language. Switching from, “you’re being so loud, you’re driving me crazy!” to “I’m feeling really overwhelmed by all the noise. I’m going to take a break” keeps the responsibility for my emotions squarely in my hands.

And when the unmothered-grief does pull me down under the surface, I remind myself what I tell my kids. It’s okay to be sad. It’s okay to be angry. Take a few breaths, go outside, read a book, do something that will help ground and regulate my nervous system. Learning to parent myself while also learning to parent my own kids is hard work, but I’m determined to end the parentification with me.

Meet the author

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Stephanie Willing is a writer and audiobook narrator. She has a BA in Dance from Texas Woman’s University and an MFA in Writing for Young People from Lesley University. Originally from Texas, Stephanie now lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons.

Tiktok: @swillingsays

Instagram: @stephanie_willing_says

Twitter: _SWillingWrites

About West of the Sea

Tae Keller meets Tracey Baptiste in a tale of generational trauma, told with a cryptozoological twist.

When her mom disappears from their small Texas town, paleontology-loving Haven is determined to find her. But as she uncovers truths about her mom’s identity, Haven also uncovers a monstrous family secret. Her mom can take the shape of a human and, in the right environment, also turn into an amphibious creature known as a kitskara. And now that she’s growing up, Haven is discovering she has this ability, too. This newfound identity is her only clue to help her track her mother and bring her back home.

And so she, her older sister Margie, and her new friend Rye set off on a road trip across Texas’s Gulf Coast to her late grandparents’ abandoned home, where they’re sure her mom has disappeared to…along with plenty of family secrets.

Infused with a deep love of fossils and Celtic mythology, West of the Sea is a lyrical, heart-filled coming-of-age story for fans of cryptozoology—and anyone who has struggled to find their place in the world when they feel different.

ISBN-13: 9780593465578

Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

Publication date: 08/15/2023

Age Range: 8 – 12 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on BlueSky at @amandamacgregor.bsky.social.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Should I make it holographic? Let’s make it holographic: a JUST ONE WAVE preorder gift for you

Press Release Fun: Happy Inaugural We Need Diverse Books Day!

Magda, Intergalactic Chef: The Big Tournament | Exclusive Preview

Fifteen early Mock Newbery 2026 Contenders

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

ADVERTISEMENT