Through the Gateway: On Horror for Young Folk, a guest post by Dan Poblocki

In the early days of VHS rentals, my family would make weekly treks to the local video store. Routinely, I’d wander to the back, where a wall of shelves stood both forbidding and thrilling. The HORROR section.

As a kid, I knew instinctively that any of the titles displayed here were out of the question, which was what drew me to them. Hiding from my parents, I’d pour over grotesque cover images: hulking figures in masks holding knives, sharp teeth in deep, dark maws, people transforming into hairy beasts. These films would surely lead to the worst kind of nightmares. And it wasn’t only the VHS tapes that tangled up in my imagination. At the town library, a similar terrifying tingle came whenever I’d peek at Stephen King’s ubiquitous door-stop novels. It. Cujo. The Tommyknockers. Possibilities of what hid between those mysterious covers both enthralled and repulsed me; most of all, they made me curious. Yet, I knew that, same as the VHS horrors, they were for adults, their contents like spooky silhouettes backlit beyond a gateway I wasn’t ready to approach.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Imagine my delight when I discovered—at my school library—a portal that led into scary worlds for people my age. I recall plucking Wait Till Helen Comes by Mary Downing Hahn from the shelf, intrigued by the image of a ghost girl glowing on the cover. Librarian approved scares? Heck, yeah! I spent the next week reading Helen again and again. I told my friends about it. I felt cool. I was hooked. And I craved more.

Lucky for me, the 1980s was one of our culture’s golden ages of creepy stuff for kids—a time when even the most benign pieces of pop-culture felt inspired to inject scares into supposedly family-friendly fare. Eventually, I didn’t need the forbidden shelves of the local video store to get my fix. Horror was everywhere, even if it didn’t look like horror. Remember Large Marge from Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure? Or Disney’s nightmarish Return to Oz? Or the existential questions raised by Wolfgang Peterson’s The Never-Ending Story? I honestly cannot say which was more traumatizing: a serial killer’s leather glove with knives for fingers or a swamp where a boy named Atreyu watched helplessly as his poor horse was swallowed by a gloopy physical manifestation of despair. (R.I.P. Artax!)

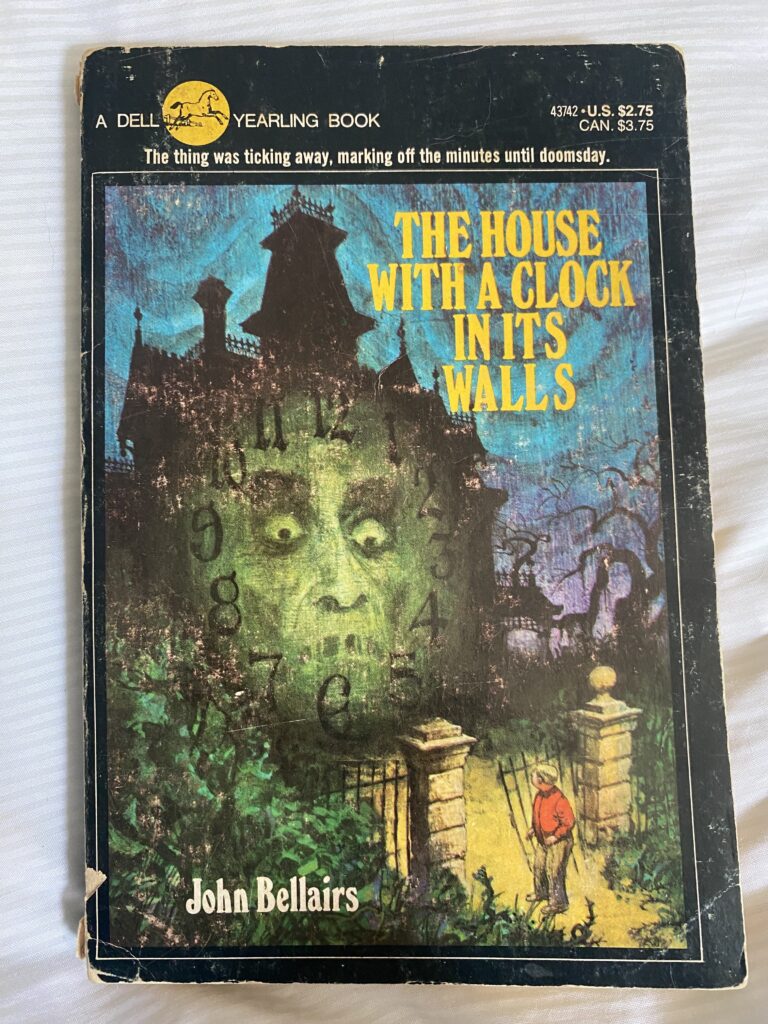

The safest kind of scares, the kind I could put away if ever they became too much, I found on my beloved library’s shelves. After Downing Hahn, I discovered John Bellairs, known for The House with a Clock in Its Walls and a number of other gothic novels for young readers. Set in 1950s American towns, festering with evil wizards, ghosts, curses, and epic Victorian houses, the books were proto-Harry-Potters for late Generation X’ers/ Xennials like myself. I’d find comfort in Bellairs’s pairings of young characters with elderly family members or friends. No matter what horrors they’d encounter, I could always depend on them being together in the end, drinking hot cocoa by a fire or a cold cola in the library.

The writer Lora Senf, a recent Bram Stoker Award finalist for her middle-grade novel The Clackity, said last year on Neil McRobert’s Talking Scared podcast that, “Kids shouldn’t have to jump to adult horror. We should provide them with the genre they want that’s appropriate for them [. . .] When you write middle grade horror, you’re entering into a contract with kids and their grown-ups [. . .] ‘If you take my hand and trust me to lead you on this journey, my promise to you is that things will be okay in the end.’ ” John Bellairs understood this. His stories explored darkness, but they were fun too, filled with relatable characters, relationships that always exuded warmth and light, silly quips, and grimly cartoonish illustrations by the inimitable Edward Gorey.

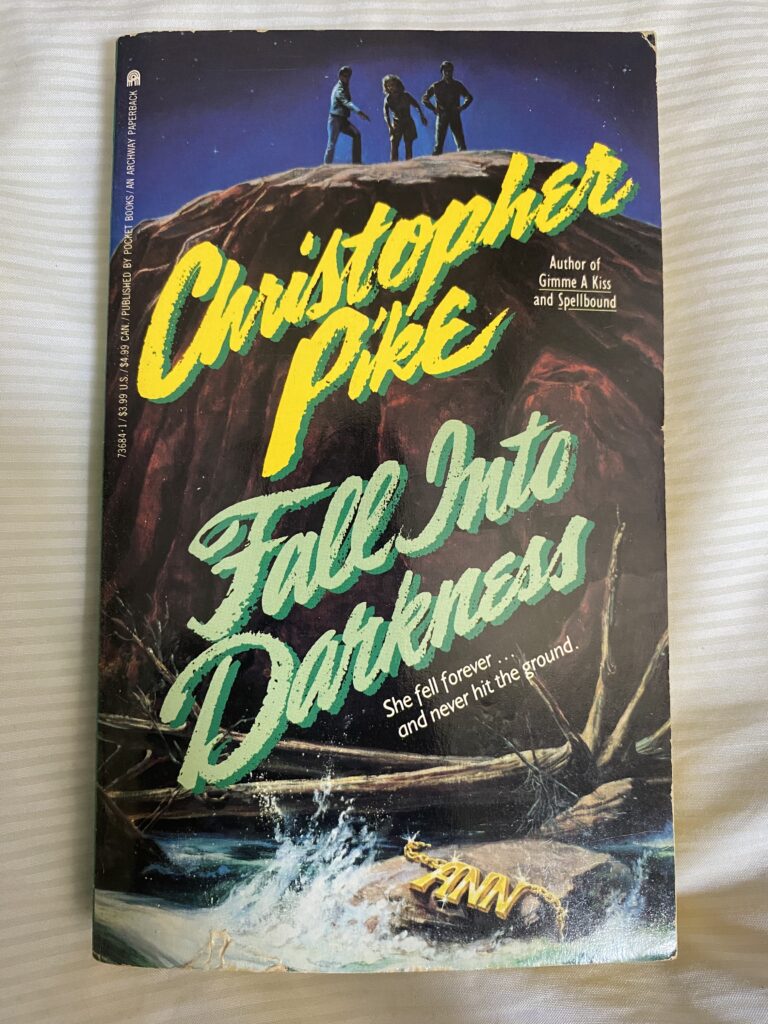

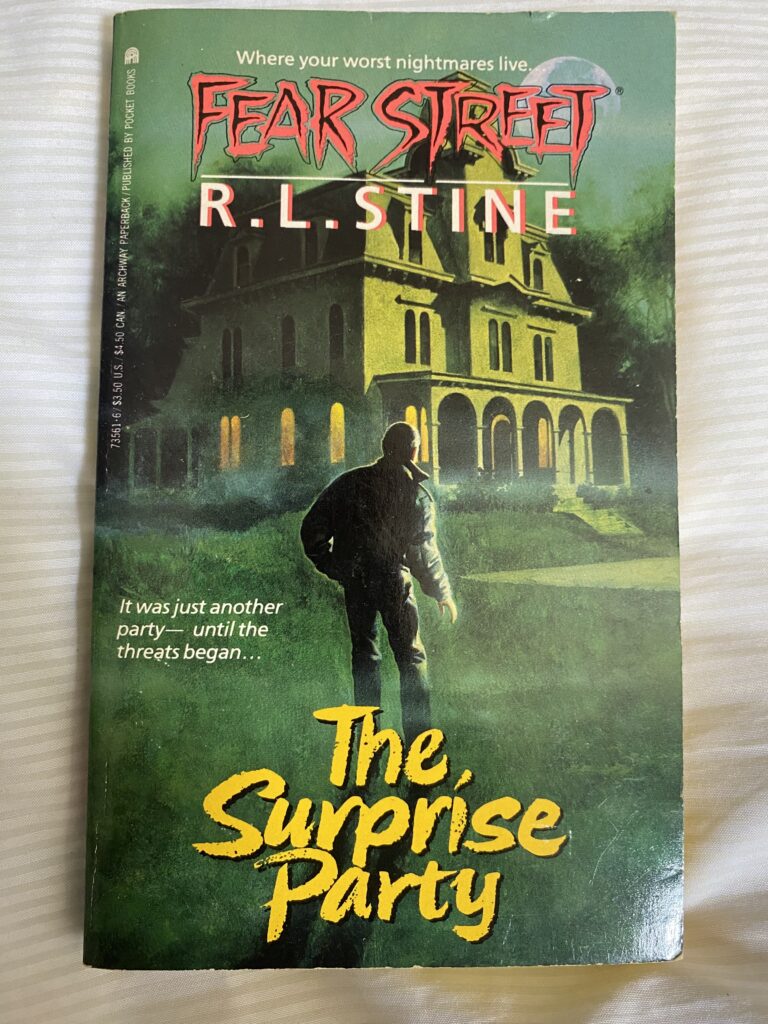

Bellairs opened the door to me for Bruce Coville, Zilpha Keatley Snyder, and Virginia Hamilton. As I aged into middle school, Christopher Pike, Lois Duncan, a pre-Goosebumps R.L. Stine, along with many others creators of Scholastic’s popular Point Horror paperbacks, wrote books stuffed with nightmarish romances, games gone awry, scary sleep-overs, evil baby-sitters, and parties where terrible teens got revenge on teens who were even worse. During the golden-age of 80s and 90s horror, kids had access to books in which ordinary aspects of our young lives were twisted inside wicked mirrors, showing us realms where the horrors of adulthood were right around the corner. Did we see these books as primers to prepare for what was to come? Or did they simply help us escape from what we thought of as hum-drum, every day existence?

The students I speak with during author visits seem to believe that it’s a mix of both. I agree.

As I was about to enter sixth grade, my family moved from Rhode Island to New Jersey. A new school, new classmates, new teachers, handing out complex assignments. To say I was anxious doesn’t come close to my reality that first autumn. Every morning felt like I was about to step off a cliff. My days started tear-stained before I managed to puff up my chest and pretend I was fine while walking the raucous, locker-lined hallways.

As ever, the school library was a haven. R.L. Stine’s Fear Street series and Christopher Pike’s Remember Me, Scavenger Hunt, and Fall Into Darkness were outlets where I could channel my fears—of navigating new friendships, of my parents’ inevitable separation, of my own confusing sexuality and gender identity, of the realization that I was not like most of my peers, in so many ways.

Change is frightening. Adolescence is change. Our bodies. Our brains. Our points of view. It’s an age where the horror genre can act as a kind of balm, or even a revelation. If you can reach the ending of a series of haunted or haunting novels, where kids survive the worst that an author can throw at them, just maybe you can make it through a day of sixth grade—of bullies, of pop quizzes, of being picked last for the team.

The internet describes “gateway horror” as something that turns a kid into a lifelong fan of the genre. The middle grade and young adult years are a kind of gateway, to early adulthood, to learning who we might become, to the possibilities of our futures. Gateway horror stands on that border that I was so tempted to cross back in my childhood video store’s aisles. Scary stories entertain but they also teach: how to struggle, how to puzzle out problems, how to succeed despite insurmountable odds. Like how Lora Senf makes a contract with her young readers, there is almost always hope in scary fiction for kids—a way through this shadow gate and out, into the light.

In the early 2000s, when I began playing seriously with the idea of writing fiction, I rediscovered my cache of old Bellairs books in my mom’s New Jersey basement. The Curse of the Blue Figurine. The Letter, the Witch, and the Ring. The Eyes of the Killer Robot. I snatched the lot out of that musty darkness and brought them all to Brooklyn (less musty, less dark) where I reread them, examining how Bellairs managed to paste his tales into my unconscious so thoroughly that I continued to long for the likes of them years afterward. Back then, I wasn’t seeing nearly as many horror titles for young folks on shelves as when I was a kid. I desired to give readers those same shivers I’d once found to be so enthralling. Soon, I started the project which would eventually become my first published novel.

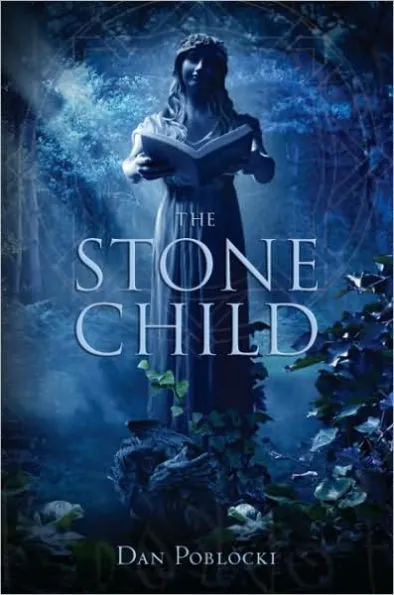

In The Stone Child, a boy named Eddie loves scary stories. His favorite author, Nathaniel Olmstead, has been missing for years, and Eddie is thrilled when his family moves to the town where Olmstead wrote. But this is where some of the horrors from Olmstead’s books still lingered. The Stone Child ended up being my love-letter to John Bellairs and Edward Gorey.

Later, in social situations, people would ask, “So . . . What do you do?” Once at a party, I mentioned that I wrote horror novels for kids. The poor woman who’d asked me the question clutched her chest. “Oh, that hurts my heart,” she said. If I’d had the wherewithal to respond intelligently, I would have told her about the emails and letters I’d gotten from parents, teachers, and librarians. About how my books helped their kids finally want to finish reading a book. About how my books helped their kids work through certain difficulties in their lives. How those messages felt like a gift. Ally Malinenko, Bram Stoker Award finalist novel for This Appearing House, tweeted recently that she writes horror “not to scare kids but to show them how brave they are.” I’ve learned over the years that horror isn’t for everyone. And some people just don’t get it. And that’s fine! But I also am certain that what I do, what so many writers have recently turned to again, has value.

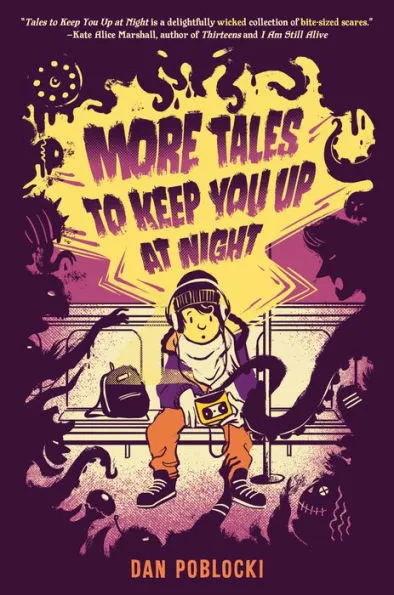

In April of this year I traveled to Austin, Texas for the Texas Library Association conference, where I met with the librarians who were kind enough to honor my newest book, Tales to Keep You Up at Night, by putting it on the Texas Bluebonnet Master List. Tales to Keep You Up at Night was my way of revisiting the most epic of all 80s horror lit for kids, Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, by the legendary pair of Alvin Schwartz and Stephen Gammell. One of the librarians mentioned that the idea of short scary stories was appealing to young readers because the bursts of horror might be more easily palatable to genre newbies than one long chunk.

Later, another librarian approached me with an old paperback of The Stone Child. It belonged to her son, and she asked me to sign it for him. She explained that I was her son’s favorite author when he was young. Now he was graduating from film school, creating ghostly scripts, directing and filming his own horror movies. She credited me for inspiring him.

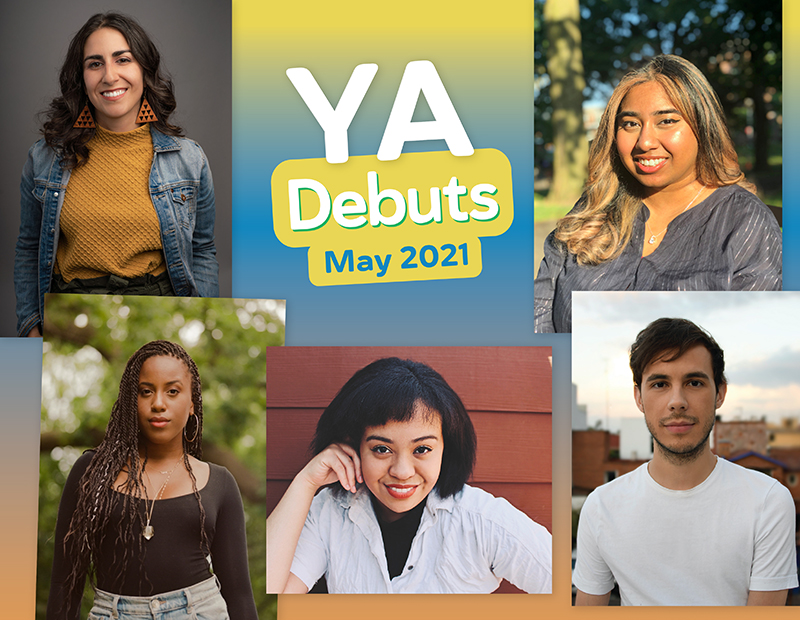

As she spoke, I felt emotion welling. I thought about the Bellairs books that I’d long ago pulled from my mother’s basement, how his frightening tales inspired me to become the author I’ve always wanted to be, how a long line of writers, going back decades, centuries, have done the same for writers who came up just after them. Writers like Ellen Oh, Ronald L. Smith, and India Hill Brown. Like Anica Mrose Rissi, Kate Alice Marshall, Lorien Lawrence, James Preller, and Ira Marcks. Like Tiffany D. Jackson, Lamar Giles, and Derrick Chow. Like Vincent Tirado, Ethan M. Aldridge, Emily Carroll, and Andrew Joseph White. And many more. Hordes more. (Did I mention yet that we’re firmly in another golden age of horror? I’ll let you ponder the whys and wherefores.)

But what a blessing it was to learn that I’d become somebody else’s John Bellairs.

If there is such a thing as “gateway horror,” I’m proud to be one who stands sentry by the darkest doorways, coaxing young souls to be brave enough and step on through.

Meet the author

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Dan Poblocki is the co-author with Neil Patrick Harris of the #1 New York Times bestselling series The Magic Misfits (writing under the pen-name Alec Azam). He’s also the author of The Stone Child, The Nightmarys, and the Mysterious Four series. His books, The Ghost of Graylock and The Haunting of Gabriel Ashe, were Junior Library Guild selections and made the American Library Association’s Best Fiction for Young Adults list in 2013 and 2014. Dan lives in Saugerties, New York, with two scaredy-cats and a growing collection of very creepy toys.

About More Tales to Keep You Up at Night by Dan Poblocki with illustrations by Marie Bergeron

From the co-author of the #1 New York Times bestselling series The Magic Misfits comes a spectacularly creepy follow-up to Tales to Keep You Up at Night that will keep you up way past bedtime.

Perfect for fans of Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark!

Gilbert is visiting his injured brother, Ant, in the hospital, when he sees a shadowed figure leave behind a satchel filled with old cassette tapes. Despite a strange, garbled voicemail telling him “Don’t listen to the tapes,” Gilbert can’t resist playing them and listening to the chilling stories they reveal: tales of cursed seashells, of doors torn through the fabric of the universe, of cemeteries that won’t let you leave, of a classroom skeleton that hungers for new skin. And wandering through all the stories, a strange man named November, who might not be a man at all…

As Gilbert keeps listening to the tapes, he slowly realizes that the stories may hold the key to helping Ant. But in order to save his brother, he may be opening a door to something much, much worse…

With hair-raising, spine-chilling prose, Dan Poblocki delivers a collection of interconnected stories that are sure to keep you up late in the night.

ISBN-13: 9780593387504

Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

Publication date: 08/15/2023

Age Range: 10 – 12 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Notes on April 2024

Lifetime Achievement Awards and Upcoming Books: A Talk with Christopher Paul Curtis

Unhappy Camper | This Week’s Comics

ADVERTISEMENT