An identity formed through protesting: How the 2019 Hong Kong protests were shaped by young people, a guest post by K. X. Song

When I was in Hong Kong in 2019, I was 21 at the time, and used to being the youngest person in the room. Earlier that year, I had taken a flight by myself in the States. When I moved to sit in the emergency exit row, a flight attendant stopped me to ask if I was old enough to sit there. (The minimum age requirement to sit in the emergency exit row is fifteen.) So that summer in Hong Kong, when my older sibling and their similar-aged activist friends invited me to attend a protest with them, I said sure, thinking I would be one of the youngest people there. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

At that particular protest in 2019, on a summer day of 89 degrees F and 100% humidity, over thousands of people turned out on the streets of Hong Kong. I saw college students waving their university banners, high school students in uniform, even junior high students lugging giant backpacks bigger than they were. Later, surveys coordinated by a team at the Chinese University of Hong Kong found that people aged 19 or younger made up 11.5% of the protests, and people aged 20 to 29 made up 46.3% of the protests. That’s over half the total population of protesters composed of young people.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

At first I wondered: why? When I was a teenager, I only knew vaguely what politics and government were–that they involved old people and big, multisyllabic words, topics and ideas outside my scope and purview. But many teenagers in this day and age not only understand that politics will impact their world, but that they can in turn, impact politics.

That summer in Hong Kong, over 2 million people came out to protest, making it the largest protest movement in the history of Hong Kong. The protests began over a bill that would have allowed extraditions to mainland China, but grew to encompass the rights of Hong Kongers in ensuring universal suffrage, free speech, and other human rights in the face of Hong Kong being subsumed under mainland Chinese control, after being handed over from the British in 1997.

In talking with Hong Kongers–whether family members, friends, or even acquaintances and strangers, I heard again and again how this movement had strengthened a communal sense of a specific Hong Kong identity. This wasn’t always the case. From being a British colony for over one hundred and fifty years, Hong Kong has long been seen as the city that could code switch between East and West as “Asia’s World City”. In this manner, many Hong Kongers–including my own family–make plans to leave Hong Kong for a western education, which is often deemed superior. And yet, during the 2019 protests, in banding together and supporting one another, in seeing the diversity of the crowds and the lengths we were willing to go to help one another–we realized how much this Hong Kong identity truly meant to us.

After returning to the States later that year, I found the western media coverage of the protests jarring. They painted the protesters, and particularly, the younger protesters, as heroes, but often in a way that felt flat, two-dimensional, and implicitly condescending. Meanwhile, the Chinese state media coverage went in the opposite direction–framing the protesters as terrorists, or as spoiled children, throwing a tantrum against their parental figures. On both sides, I felt the lack of nuance and depth, and the ease at which consumers can forget the real people behind these news headlines. That was when I set out to write my own story.

Today, the protests in Hong Kong are largely eradicated. It is too dangerous to protest openly on the streets, when the National Security Law, passed in 2021, enables protesters and anyone “endangering national security” to be punished with sentences ranging from fines to lifetime imprisonment.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

But that sense of community and identity hasn’t been erased. In fact, I’ve only seen it strengthened amongst diaspora Hong Kongers who have chosen to leave for one reason or another. The sense that even as a young adult, I have agency in where I call home, in how I define myself, and how I choose to live in this world, as unpredictable and unfeeling as it sometimes may appear. Even though we can’t always control the various storms of life, we can control and change the way we respond to those storms. As in the case of the Hong Kong protests, and the community formed as a direct result of them, that response can turn into a beautiful thing.

In late 2022, I attended an exhibition opening featuring a Hong Kong diaspora artist, and later that night, went out with other Hong Kongers after the museum had closed.

Chatting with one Hong Konger who had moved here during the pandemic, I asked him what he thought about that term.

“To be honest,” he said, “I never really used it before 2019. But now, even though I no longer live in Hong Kong, it’s how I see myself–more than ever before.”

Meet the author

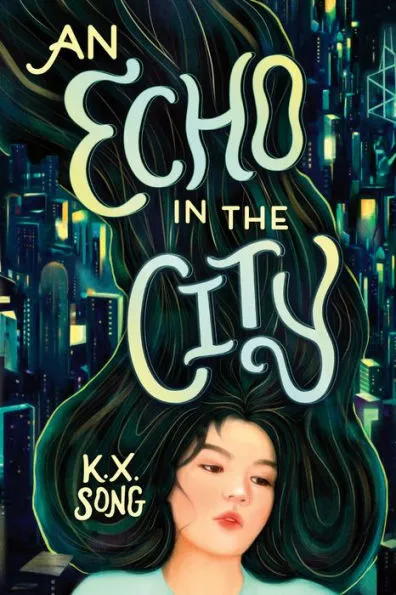

K. X. Song is a diaspora writer with roots in Hong Kong and Shanghai. An Echo in the City is her debut novel. Visit her online at kxsong.com, or on Instagram @ksongwrites.

About An Echo in the City

Two star-crossed teenagers fall in love during the Hong Kong protests in this searing contemporary novel about coming-of-age in a time of change.

Sixteen-year-old Phoenix knows her parents have invested thousands of dollars to help her leave Hong Kong and get an elite Ivy League education. They think America means big status, big dreams, and big bank accounts. But Phoenix doesn’t want big; she just wants home. The trouble is, she doesn’t know where that is…until the Hong Kong protest movement unfolds, and she learns the city she’s come to love is in danger of disappearing.

Seventeen-year-old Kai sees himself as an artist, not a filial son, and certainly not a cop. But when his mother dies, he’s forced to leave Shanghai to reunite with his estranged father, a respected police officer, who’s already enrolled him in the Hong Kong police academy. Kai wants to hate his job, but instead, he finds himself craving his father’s approval. And when he accidentally swaps phones with Phoenix and discovers she’s part of a protest network, he finds a way to earn it: by infiltrating the group and reporting their plans back to the police.

As Kai and Phoenix join the struggle for the future of Hong Kong, a spark forms between them, pulling them together even as their two worlds try to force them apart. But when their relationship is built on secrets and deception, will they still love the person left behind when the lies fall away?

ISBN-13: 9780316396820

Publisher: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

Publication date: 06/20/2023

Age Range: 14 – 18 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on BlueSky at @amandamacgregor.bsky.social.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Should I make it holographic? Let’s make it holographic: a JUST ONE WAVE preorder gift for you

This Whole Interview Is a Mistaco: And I Get to Talk to Eliza Kinkz in the Course of It!

Betty and Veronica Jumbo Comics Digest #334 | Preview

Fifteen early Mock Newbery 2026 Contenders

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

ADVERTISEMENT