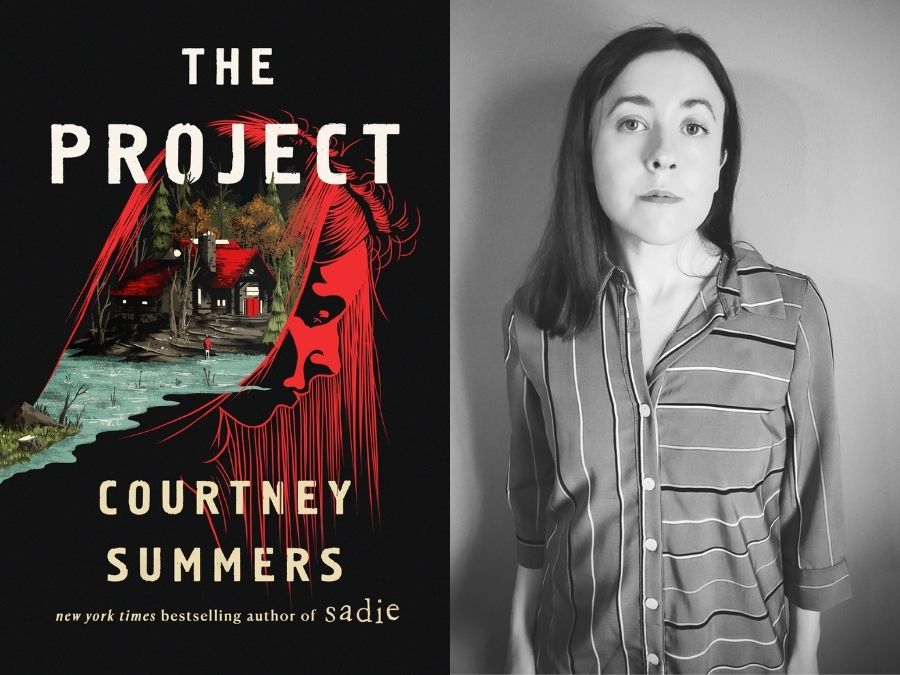

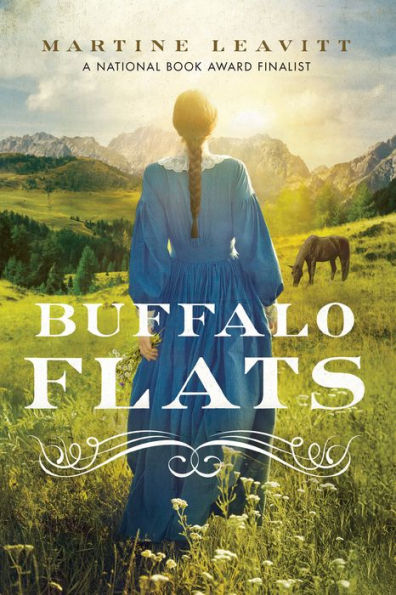

How BUFFALO FLATS Flattened Me: Turning Your Family History into Historical Fiction, a guest post by Martine Leavitt

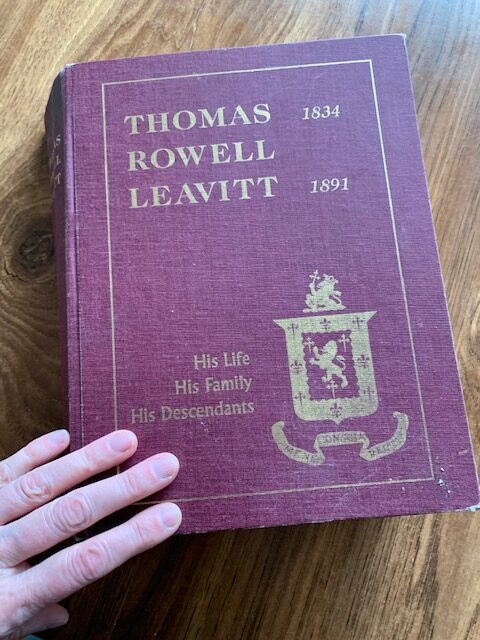

I blame it all on the “big red book.”

The big red book, affectionately so-called by the descendants of Thomas Rowell Leavitt, is a collection of the personal histories of my pioneer ancestors stretching back to the 1840s.

I first read it with delight and astonishment. Why, here were treasures untold for the writer ever looking for a good story! It was all there for me: characters whom I knew practically at the genetic level! a setting I was familiar with since childhood! plot possibilities galore – births, deaths, love, longing, and a lot of hard, joyous life. It solved all the problems! Any writer possessed of such riches would be in heaven! Any writer worth her salt would find it so easy to get a book out of these riches…

Unless, of course, the writer was me.

Turns out the journey to my particular writerly heaven was going to involve a bit of a detour through hell. So if you have a story from your family history that you think would make a good book, here are a couple things I learned on my journey. Save you the trouble.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

focus

The big red book was almost a thousand pages long, and virtually every page had a gem in it, a mini-story. Some of this stuff I couldn’t make up – the man whose fiancé breaks the engagement, so he hides the $2,000 diamond ring in the forest for anyone to find; the fearless Blood ponies who rescue a herd of snowbound cattle; the boy who, caught in a deadly prairie blizzard with only a light jacket, prays his way into a haystack where he warms himself among some pigs who had also sought refuge there… Which of these many mini-stories would I use? Why all of them, of course! I choose you all!

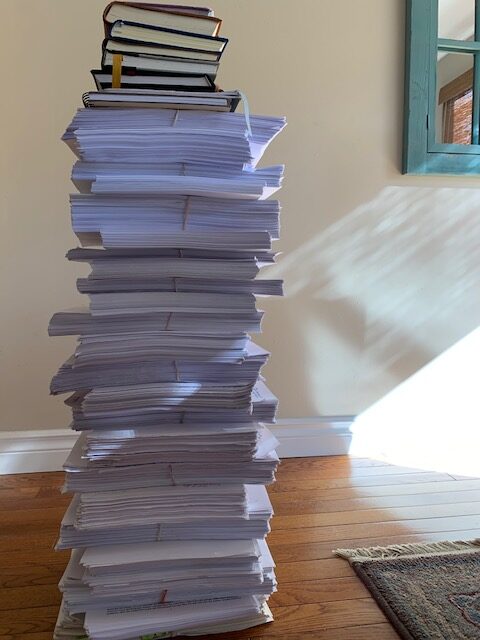

If only, if only. Writers who make up stories whole cloth have to look into the great bloody eyeball of infinite possibility. My possibilities weren’t infinite, but they were still pretty daunting. Choices had to be made. Which of all the beautiful bits would end up in my pages? It was so hard to whittle down, discard, sort through, but I was brave. The draft I first sent to my editors was a mere 430 pages long and spanned four years of my character’s life.

It would take as many years for my editors, the brilliant Margaret Ferguson and Shelley Tanaka, to slowly, painfully, make me see how much more needed to be discarded in order to bring focus to the story. Not a story spanning four years, they said – one year will do. Not the whole history of the Northwest Territories – just the tale of one important part. A whole book still had to be edited out of my book! Dead darlings were everywhere – some of them still twitching to this day. It took time for me to see the importance of distilling all those pages down to showcase the heart of the story.

Recently I stacked up the versions of Buffalo Flats and found they came almost as high as my waist. It would be better if you did it yourself, rather than wearing out your editors.

research

I also had to come to grips with the fact that my ancestors didn’t tell me everything. I had these marvellous accounts written by people of the time, but people writing about their own lives in their own times often don’t stop to mention the things that are everyday and obvious to them. For example, they stored food to get them through the winter – what food? They polished the wood stove – what kind of wood stove? They chopped down trees to heat their homes – what kinds of trees? They cooked for the canal workers. What canal? When they cooked outdoors, flies fell into the pot – what was in the pot besides flies? What kinds of wagons did they use? What kinds of flowers would they see? What is a horse? Okay, I knew what a horse was, but I didn’t know many things about a horse, or even anything about a horse, and I had to know, even if it didn’t make it onto the page. This was to be historical fiction, after all. It should probably be… historical.

In the past, my research involved going to the library and checking out children’s nonfiction books on the subject. This is Jeopardy champion James Holzhauer’s secret weapon, too, after all. This time I had to dive deeper.

But there was a problem. I have a mild version of OCD called spartanism. What that means is that I have a great urge to give away or throw away everything. If I can pick it up and put it in a garbage or recycle bin, or into the trunk of the car for a trip to the thrift shop, it’s not safe with me. I have drawers with nothing in them. I have shelves with nothing on them. I look at my empty shelves and drawers and they make me happy. The delete button on my computer is my most best-beloved button. Sometimes this all works for me. Sometimes it’s a problem. Over the years I had thrown away previous drafts of novels as soon as I had the next draft. By the time the book came out, that was all there was – the physical book – as evidence that I had worked on it. This time, for whatever reason – perhaps because I had an instinct that this was going to make a good story – I decided to keep most of the drafts of Buffalo Flats. I kept them very tidily in a bin in the basement where I didn’t have to look at them – too tempting.

What I didn’t keep – just couldn’t keep – was my research notes. I would thread my learnings into the draft, and then throw the notes out as soon as ever I could. Writers of historical fiction – real writers of historical fiction, that is – will shiver with horror upon reading this. No, no, no! they will be saying. You save and file your notes, you save links and quotes, you collect images. You write down what you find and where you found it. Label! File! Cite!

I couldn’t bear it. The only file I used was the round file. When I needed to verify some factoid, or if my editors wanted follow-up details, the evidence was gone. Sometimes I had to do the research all over again. Sometimes I would eradicate a lovely bit just so I wouldn’t have to do the research all over again. Someone like me should never write historical fiction.

But these were my people. This was my story to tell. And I had to tell it. If you are writing a book based on family stories, when it comes to research, do as I say and not as I did.

story

A thousand pages of mini-story gems does not a novel make, no matter how jewel-like and twinkly they may be. My story needed to be a cohesive whole. It needed a thematic shape. I kept waiting for this to happen, and it kept not happening. Finally, I said, quoting Margaret Bechard, “Do I have to do everything myself?” The answer was yes. Yes, you do.

You may find your over-arching story through your research. None of my female Leavitt ancestors complained in their brief life stories about the status of women in their day. I suppose most were too busy getting supper on the table to question how oppressed they were. Most were valued and respected partners to their husbands, acknowledged as essential to the survival of their family and their community.

My protagonist, however – my Rebecca – was not too busy to bump up against some of the patriarchal structures in place. I wondered how she would feel about not being allowed to take out a homestead like her brothers because she wasn’t a “person” under the law. Women’s status and power, or the lack thereof, became a major theme. I wanted to explore their soft power, how female relationships were a force in family and community dynamics. But I also wanted to show how some women, without legal recourse, were undoubtedly vulnerable to weak, twisted men. That wasn’t talked about in the big red book, but I have a pretty decent imagination for what isn’t talked about.

Even with all that delicious true history abounding, it was my fictional character Rebecca, and the questions she kept asking me, that made Buffalo Flats into a cohesive story.

go for it!

I make it sound like it was hard to write Buffalo Flats. And oh, it was – the hardest of my books to write by far! But it was also joyous, and deeply meaningful. If you have inherited a story from your progenitors that you think might make a book, go for it. It’s worth a little detour through hell.

Meet the author

Martine Leavitt is the author of award-winning books for young readers, including Calvin (winner of the Governor General’s Award), My Book of Life by Angel (finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize and winner of the Canadian Library Association Young Adult Book of the Year) and Keturah and Lord Death (finalist for the National Book Award). She teaches in the MFA program in Writing for Children and Young Adults at Vermont College of Fine Arts, where she is serving as the Katherine Paterson Endowed Chair. Martine lives in High River, Alberta.

About Buffalo Flats

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Based on true-life histories, Buffalo Flats shares the epic, coming of age story of Rebecca Leavitt as she searches for her identity in the Northwest Territories of Canada during the late 1800s.

Seventeen-year-old Rebecca Leavitt has traveled by covered wagon from Utah to the Northwest Territories of Canada, where her father and brothers are now homesteading and establishing a new community with other Latter-Day Saints. Rebecca is old enough to get married, but what kind of man would she marry and who would have a girl like her—a girl filled with ideas and opinions? Someone gallant and exciting like Levi Howard? Or a man of ideas like her childhood friend Coby Webster?

Rebecca decides to set her sights on something completely different. She loves the land and wants her own piece of it. When she learns that single women aren’t allowed to homestead, her father agrees to buy her land outright, as long as Rebecca earns the money —480 dollars, an impossible sum. She sets out to earn the money while surviving the relentless challenges of pioneer life—the ones that Mother Nature throws at her in the form of blizzards, grizzles, influenza and floods, and the ones that come with human nature, be they exasperating neighbors or the breathtaking frailty of life.

Buffalo Flats is inspired by true-life histories of the author’s ancestors. It is an extraordinary novel that explores Latter-Day Saints culture and the hardships of pioneer life. It is about a stubborn, irreverent, and resourceful young woman who remains true to herself and discovers that it is the bonds of family, faith, and friendship—even romance—that tie her to the wild and unpredictable land she loves so fiercely.

ISBN-13: 9780823443420

Publisher: Holiday House

Publication date: 04/25/2023

Age Range: 12 – 17 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on BlueSky at @amandamacgregor.bsky.social.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2025 Books from Stonewall Winners

Fuse 8 n’ Kate: It’s Not Easy Being a Bunny by Marilyn Sadler, ill. Robert Bollen

Band Nerd | This Week’s Comics

30 Contenders? Our Updated Mock Newbery List

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

ADVERTISEMENT