Don’t Ban Them. Don’t Silence Them. The Importance of Writing About the “Tough Stuff” in Teen Fiction, a guest post by Lila Riesen

Radicals are change makers. Radicals tell it like it is.

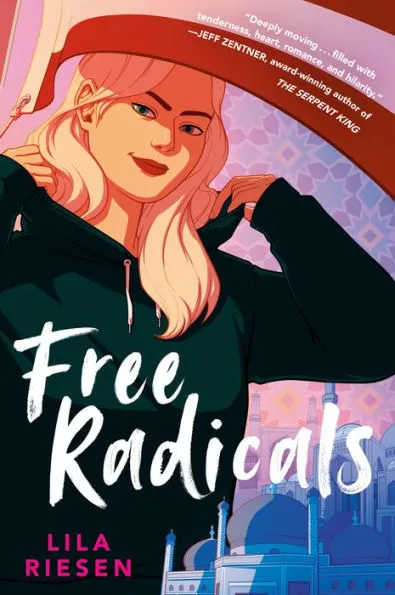

I want to be a radical, a positive agent for change, but unlike character Mafi in Free Radicals, I’m still harnessing my bravery. Often, I write characters who are braver than I am, hoping their courage might rub off on me. I’m sweating as I write this post, much like I did when I wrote this published book of mine, but here we go. I’m doing this for teenage Lila.

I was in graduate school when I told a classmate in my MFA program that I was working on a young adult novel. “Why not adult?” he asked, eyebrow hitched. “Why would you want to write that sarcastic fluff?”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Suffice it to say, I sat somewhere else the next day.

There’s this general implicit attitude that writing for young adults is somehow inferior to writing for adults. I felt it in grad school, not only from my peers, but from select teachers, too. But it’s not quite accurate to say writing for young adults, considering that adult readers frequent the young adult section perhaps even more than teens themselves. To me, writing young adult fiction means only one thing: the main character is between the ages of 14 and 18.

Everything else is raw. Real. No “sarcastic fluff.” As a young adult author, I have a duty not to shy away from darker themes.

To some readers—mostly adults, who are under some fallacy that teenagers will remain innocent so long as we shelter them from difficult themes—my book will be one giant red flag. My take is that if you are an author of young adult fiction, you better include difficult themes in your book. You better show real, valid, teen struggles. Think back; how many struggles can you remember?

If your book paints some teenage utopia where everyone gets along and the characters face zero adversity, young adults who read it will likely chuck the book across the room, and not in a good way. In a DNF sort of way.

In a world where their favorite books are being banned, their rights are being stripped, their school hallways ring with gunfire—and for some—simply living their truths and existing is seen as an abomination, they don’t live in utopia. Far from it.

Contrary to the beliefs of some, writing about difficult themes will not monopolize the young adult market. Banning books does incredible harm to teens who are just starting to self-actualize, who are beginning to know themselves, accept themselves, and be contented with who they really are—not who others want them to be. What do we tell our readers—of any age—who finally find a book that speaks to them? Who see themselves in books that explore racism, mental illness, sexual abuse and assault, familial trauma, religion, poverty, sexuality, suicide, and drug use? What does banning books that deal with difficult topics tell the teen that has faced adversity? That they’re unworthy/dirty/judged/abnormal?

Silence the shame.

In addition to writing, I have worked as a self-defense instructor for teens and an English and exercise science lecturer at a trade school. This particular college had a booming veteran population. In class, we discussed Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and how the dystopia reflected is not so far from our own reality.

Every semester, and in every self-defense class, students, young adults, would open up about the atrocities they’d witnessed at war. Not only gunfire and death. The behind closed doors things, too. Pain they’d endured at the hands of someone in their circle, someone they’d trusted and considered a friend. Atrocities they’d witnessed at home. Atrocities they’d carried for years.

Life is messy. It is a kaleidoscope of emotions and experiences—all of which make us human.

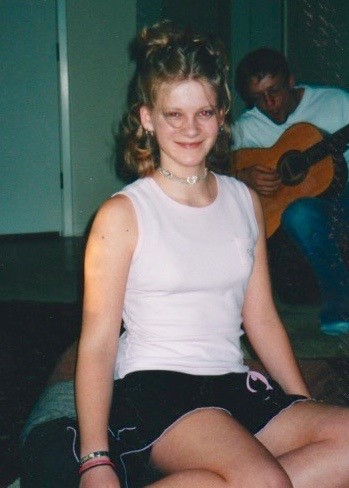

To strip us of our past traumas, to place a ban on the voicing of them, the reading of them, removes our humanity. Thwarts the healing we all, if we’re lucky, will undertake when we’re ready. I was fourteen, on the school bus home, when an upperclassman—a neighbor—put his hand on my leg. Nothing more. He merely rested it there and looked out the window as if the unsolicited touching was the most normal thing in the world. I was wearing a new jean skirt from American Eagle that I couldn’t wait to show off at school. Heart racing and peering down at his hand, I wished I’d gone to school in a garbage bag. Because that’s how I felt… like garbage.

He never said a word. And me? I froze. I’d been practicing martial arts since I was three, broken boards and everything, and I froze. Oh, the shame. Later, in bed, a voice in my head told me I was weak. That wearing the skirt probably meant I was asking for it. That my silence was consent.

I never confronted the boy. And I’m unsure I would now, even as a full-fledged adult with a baby on the way.

As I said, life is messy.

When Sex Education came out on Netflix and Amy was assaulted on the bus, I stood and watched with my hand cupped to my mouth. A mix of emotions poured out of me: sadness, elation, relief, disbelief. Someone was writing about this! Someone was normalizing the fact that unwanted touching is commonplace for women!

PS—thank you, Laurie Nunn.

At thirty years old, I went back in time and told fifteen-year-old me, “See, we’re not so alone!”

In Free Radicals, there are two scenes where our main character, Mafi, feels particularly unsafe. At school, she wears sweatpants and hoodies after a rumor spreads about her and boys start ogling her on a daily basis. This illustrates the feeling that many women have, that our clothing choice dictates whether we are “asking for it” or not. Mafi feels that she must change the way she dresses in order to fade into the background again. Eighth grader Lila retired that American Eagle skirt pretty quickly, too.

In the first scene where Mafi feels unsafe, she’s cornered by upperclassmen in a bathroom at a party and narrowly escapes. In the second, a car slows behind her as she walks home in the dark. Will I get home tonight? Are they slowing to abduct me? Hurt me? These are realities most teens will face. Are facing.

Every teenager, no matter who you are, has experienced the back of the neck, hair raising feeling that warns them they’re in danger. There’s value in books that deal with difficult topics and reflect the not-so-nice realities of growing up.

Of course, I write about the humorous stuff, too. Because there’s definitely a lot of that in our teen years: times spent doubled over, laughing with friends; flirting with crushes before leaning in for a kiss; playfighting with siblings in the checkout line at the mall.

As I said, life carries with it a kaleidoscope of feelings, emotions, experiences.

I write about difficult topics to help not only current teens, but the teenager in all of us that felt alone or scared after experiencing something that deviated from the happy-go-lucky “norm.” For me, my “norm,” or “happy place,” was watching Father of the Bride and looking forward to the day that I’d find my partner. After the unwanted touching on the bus, I suddenly worried that I was unworthy of love. That I was unworthy of being my father’s daughter. Was I tainted?

In Free Radicals, Jalen Thomas’s dad deals with his own mental health struggles, and it affects how he interacts with his son. I applaud the recent movement, primarily in the US, to destigmatize mental illness as some flaw or weakness.

Hailing from a South Asian/Australian background, mental illness was often a taboo topic—one definitely not discussed at the dinner table. Many of us suffer in silence. Ignoring the struggles of others won’t make those struggles magically disappear. They burrow. Fester. And are sure to surface later, in adulthood.

The answer is empathy. As a born empath who comes close to tears every time she accidentally trods on an ant, it comes—perhaps—too easily for me. Empathy is a muscle that can be trained, built up, like any other muscle in the gym. Muscles must be broken down during training so that they can be built back up. Stronger. Sturdier. We must break down our stereotypes and unconscious biases to build back up again—as better versions of ourselves. More empathetic versions of ourselves. And the “training” we must do to build empathy is reading, and reading widely.

We can develop empathy for people who differ from us when we read diversely, and read about lived experiences that are not our own. Growing up in Indiana, 95% of my teachers were white. We’ve all seen the sickening TikToks that some unthinking parent has posted of their child’s face, thinking it “cute” or “funny” when the child spots someone of a different race for the first time and screams or runs away.

Fear. Fear breeds hatred. We hate what we are not exposed to. We hate what we don’t understand.

It starts with adults. It is our job to ensure that diversity and inclusion is not only talked about, but practiced. In our schools, our places of work, our communities. This means hiring teachers of different backgrounds so that children can be exposed to new cultures, tongues, beliefs, and ways of life.

Mafi, too, deviates from the “norm.”

She is Afghan-American, but with her blonde hair and fair skin, she doesn’t look like a stereotypical Afghan, like her siblings. But there is a difference between race—her physical appearance—and heritage. No matter how she appears, she is still Afghan. Mafi comes from a background where Islam is the practiced, but her dad considers converting to Christianity to prove to Americans that the Shahin family is not a threat. Mafi’s baba, her grandfather, is a “conditional Muslim” half-participating in the religion. Mafi thinks often about hooking up with her crush—which would be forbidden before marriage in her inherited religion. With her blonde hair, fair skin, and less-than-adequate Farsi skills, she offends other Afghans who see her and her family as “doing it wrong.” In Afghanistan, many would consider her family to be traitors and deserters. This is further complicated by the fact that her relatives never wanted to leave Afghanistan, but felt their hand was forced after the Taliban rose again. Afghanistan was home. And to other Americans who believe that Afghans were responsible for the terrorist attacks of 9/11, the Shahins aren’t so welcome in the USA, either. Assimilation is not so easy.

Mafi realizes that in order to be herself, she needs to simply “be.” No more identity vs. role confusion.

Mafi’s experience might not match every reader’s, but perhaps each reader will find something in the novel that speaks to them. Something they didn’t understand before.

With that said, there’s an unspoken expectation placed upon authors writing about non-white or white-presenting characters that they are required to make some daring statement or speak for all individuals of that particular group. Mafi’s experience as the child of an Afghan immigrant father and a white, American mother will vastly differ from others who identify as Afghan-American—and that is okay. She is not religious, she doesn’t speak Farsi, she has a beautiful and diverse group of friends, and she is open about sex.

Many will not agree with this. Many will hate Mafi for this. And because shelves aren’t overflowing with books with Afghan-American representation (yet!), readers must note that this is only one story. One piece of the puzzle. One fragment of glass in the kaleidoscope. Turn the gadget over, and you’ll see another reality reflected through the lens. Now, how beautiful is that frame?

Free Radicals is not meant to be didactic or preachy by any means, and readers should not think that this is how every Afghan-American family thinks or acts. All Afghan-American families will have different traditions and beliefs and it is important to reflect the reality of that.

This is Mafi’s story.

In many ways, it is my story.

I will continue to do the work so that I can internally and externally “be.” Be braver, too. I’ll end this novella of an article with this: only we have the power to free ourselves from the prisons of our own making. Only we have the key.

In the end, it’s important to remember to be you. They’ll adjust. Our authenticity is our power source.

Like Jalen in Free Radicals tells Mafi: “People become who they expect themselves to become.” I expect myself to become braver. To stand up for myself and others. To practice radical acceptance. To speak up, even when my voice shakes (and sweat snakes down my back).

Here’s to the courageous young radicals who have dedicated their lives to making a real-world impact: Greta Thunberg, Hunter Schafer, Desmond Naples, Marley Dias, Malala Yousafzai, Genesis Butler, and so many more—we see you.

And now, go on: read more banned books. You are not alone.

Meet the author

Daughter of Afghan and Australian immigrants, Lila was raised in the USA. Her undergraduate studies were completed at Indiana University and the Australian National University in English. In 2017, Lila graduated with a Master’s degree in English literature and linguistics from the University of Zurich in Switzerland. Free Radicals is her first novel, inspired by her cashew-covering Baba and all the Afghans fighting for peace, in the US and abroad.

Author socials:

Instagram: @lilariesen

TikTok: @lilariesen

Twitter: @lilariesen

Website: www.lilariesen.com

About Free Radicals

Afghan-American Mafi’s sophomore year gets a whole lot more complicated when she accidentally exposes family secrets, putting her family back in Afghanistan in danger in this smartly written YA debut.

Sixteen-year-old Mafi Shahin is well-aware that life is not always fair. If it was fair, her parents might allow her to hang out with a member of the male species, other than her cat Mr. Meowgi. If it was fair, her crush and basketball hottie Jalen Thomas might see her as more than just her brother’s kid sister. And if it was fair, her baba’s brother and wife would be able to leave Afghanistan and come to America.

Life might not be fair—but she can make it a bit more even. Working as the Ghost of Santa Margarita High, Mafi serves dollops of justice on her classmates’ behalf as the school’s secret avenger. They leave a note declaring the crime and Mafi ensures the offender receives an anonymous karmic-sized dose of payback. Keeping her identity as the Ghost a secret sometimes means Mafi has to lie. But as those lies begin to snowball both at school and at home, even compromising their family’s secret past and putting their relatives back in Afghanistan at risk, Mafi is forced to decide how she wants to live her life—trying to make the world more fair from the shadows or loudly and publicly standing up for what’s right.

ISBN-13: 9780593407714

Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

Publication date: 03/21/2023

Age Range: 12 – 17 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Coretta Scott King Winners

The Ultimate Love Letter to the King of Fruits: We’re Talking Mango Memories with Sita Singh

Monkey King and the World of Myths: The Monster and the Maze | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT