Black Patriotism in America, a guest post by Alana Tyson

In 2016 when my oldest son was nine, I embarked on my annual journey to Old Navy to splurge on summer gear that would last just long enough for him to outgrow. Prepping for longer days and trips to the beach was always a treat at the end of a seemingly long Spring. Buying shorts and tees that screamed “That kid’s got a stylish, yet thrifty mom” was often the highlight of my Saturday mornings. But on one particular spree, I didn’t realize I’d light a spark that would fuel me some four years later, propelling me to this very moment; the birth of a children’s book I didn’t know was needed.

As enjoyable as summer shopping was back then, 2014-2020 wasn’t all fun and flip-flops. It was a tumultuous era in the United States, filled with grief, unrest, civic discord, and a very divided country, as many cities dealt with countless murders of unarmed people of color, mostly Black males. George Floyd, Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Philando Castile, Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland, and Walter Scott are only a few of the names. Shopping for my son was, in a way, a reprieve, as I harbored a constant fear: Would my son be next? Would my husband be next? Would I be next? Would we also become headlines? Being Black in America was difficult in the 19th and 20th century, but this was the 21st century. How had something so fundamental remain unchanged?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

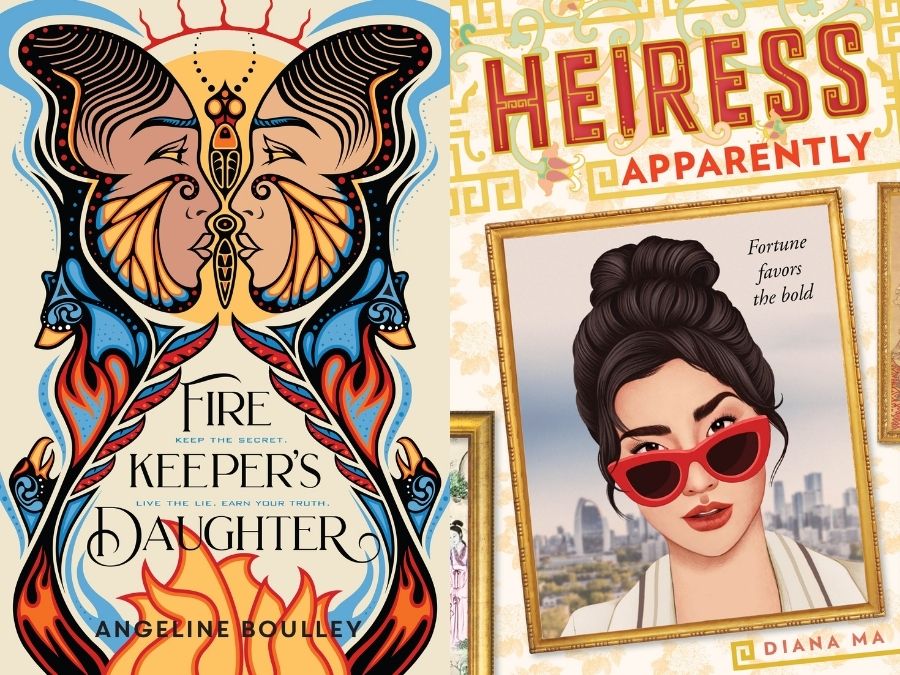

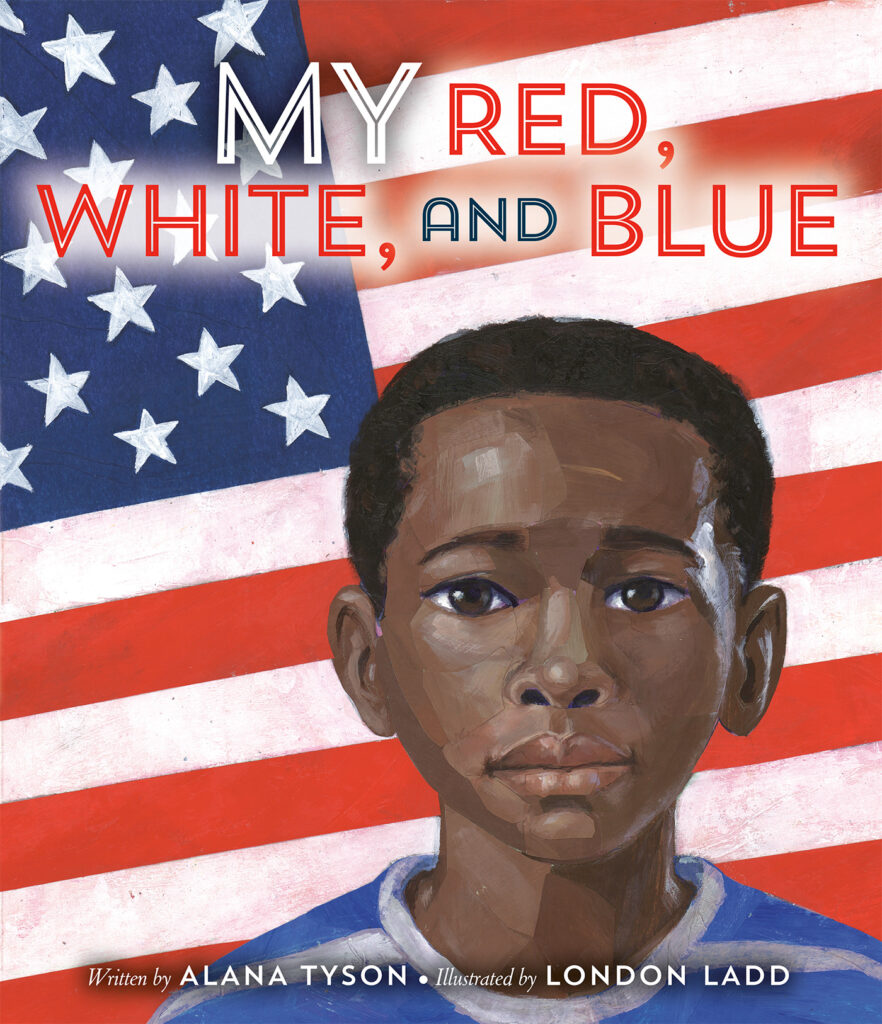

As I browsed through Old Navy racks, I spotted a T-shirt that had my son’s quirky nature written all over it. The shirt was part of the July 4th collection and displayed the US flag, in a vertical position. It was vibrant, playful, and stylish. As I reached for it, I paused and thought: How on Earth could I allow my Black son to wear a US flag while our Black communities are hurting? Families were being dismantled, children were losing fathers, mothers were losing sons, the Black race was being attacked while the world watched. During that time, San Francisco 49ers player Colin Kaepernick did something many hadn’t seen in decades: he refused to salute the flag in Black solidarity and to call attention to the mass killings of unarmed citizens. Rather than salute, Kaepernick decided to kneel during the anthem, a silent protest that many of his fellow NFL colleagues followed. What message would my nine-year-old send, as a Black child wearing the US flag? Would he be ridiculed or called a traitor? In that same breath, I also thought: But we’re American as apple pie. I was born in Brooklyn, NY, my parents were from Harlem, NY and Savannah, GA; my son’s grandparents taught at the University of Virginia, and I worked for the federal government and had been protecting national security for the last thirteen years. Yet there I was, questioning and perhaps defending, my right to display American pride because of my skin color. At that moment, I realized I was torn. Could a Black person be loyal to their race and the United States simultaneously? I wondered how many other Black families struggled with the idea. How many children struggled with the idea as they watched the media’s coverage and takes. Are Black veterans conflicted? So many questions came from this simple act of buying a T-shirt with my country’s flag. I was determined to explore it further, but in a way that the youngest of minds could relate. Hence, the creation of the picture book My Red, White, and Blue, illustrated by London Ladd.

Now, the title of this post may be questionable to some, which is understandable if you’re not Black. “Why Black patriotism?” “Aren’t we all Americans?” The qualifier is necessary because no other race of people in America have been as disproportionately mistreated as Black Americans. The Civil Rights Act of 1968 proves that. Along with statistical data collected by the FBI and federal organizations whose role it is to research financial, judicial, and social injustice. I imagine patriotism comes easy for people who are treated justly. But for those who aren’t…not so much. Expecting it to be easy for Black Americans would be like expecting Cinderella not to feel SOME disdain toward her evil stepsisters.

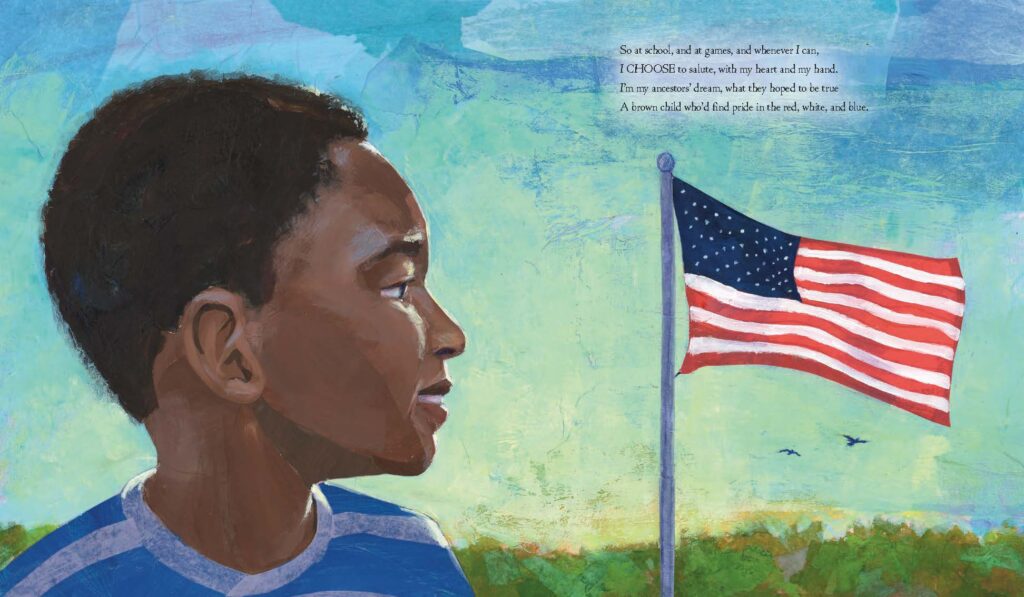

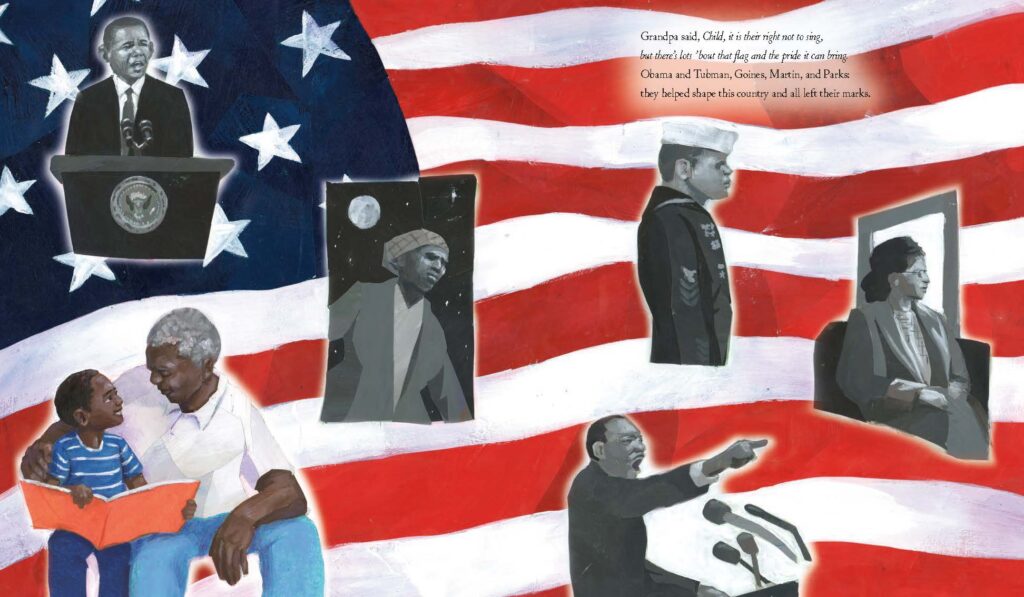

I bought the shirt. And when I gave it to my young son, I also gave him a lesson on what it means to be Black and American. What he should tell anyone who questions his decision to wear the US flag. His ancestors—our ancestors—earned the right to live, work, and prosper on American soil. Our ancestors helped build America via the slave trade. Many fought and died for me to have the right to walk through the front door of a retail establishment such as Old Navy. He is his ancestor’s dream, a Black child who would live a good life, one day, in America. So yes, Black Americans who are descendants of those enslaved, earned the right to be patriots and we shall wave (and wear) our flag in honor of those who couldn’t. Choosing to salute the flag doesn’t mean disagreeing with Kaepernick’s message—a message that is less about the flag and more about equality. A silent protest of the flag is not unpatriotic. Let me repeat that: A SILENT PROTEST OF THE FLAG IS NOT UNPATRIOTIC. Two of the most iconic American ideals are freedom of speech and choice. It’s both of these that allow a person to either embrace elements of the flag that resonate for them or reject the elements that don’t. As a Black American, embracing the flag to me means saluting my race’s fight and tenacity. It’s not allowing others to co-opt the flag in an effort to claim it as theirs and theirs alone. It’s embracing the never-ending fight for civil rights and racial equality. And it’s paying homage to those who worked tirelessly toward the right that “all men are created equal.”

In 1968, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, two Black American athletes who received Olympic medals in Track and Field, used their platform to make a statement, much like Kaepernick did in 2016. While receiving their medals during the national anthem ceremony, they both bowed their heads and raised a gloved fist in the air, calling attention to the need for change in the United States in the areas of civil rights and racial justice. Just six months prior, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy had both been killed and the US was in turmoil over civil rights and the Vietnam war. While they should have been celebrating their Olympic victories, the weight of the country’s issues were too heavy to ignore. The iconic photo is perhaps one of the most recognized images in American sports history. In an interview years later, Tommie Smith stated that their actions were not about the flag at all. Rather, about using a moment and a public stage, to call attention to a problem. Smith later said their action was “a cry for freedom and for human rights. We had to be seen because we couldn’t be heard.” Much like Kaepernick, their acts were courageous and selfless, and they all paid a price for using their platforms to advocate for equality. Kaepernick was fired from the San Francisco 49ers and blackballed from the NFL. Smith and Carlos were both banned from the Olympics, suspended from the US team, and their medals and potential endorsements all stripped away. The Olympics were supposed to celebrate the human spirit, yet the human spirit of so many in the United States was being crushed. Smith stated they were both human first and seized the opportunity to take a stand. In November 2019, Smith and Carlos were both inducted into the US Olympic and Paralympic Hall of Fame, 51 years after the incident, a decision by the US Olympic Committee indicating a public apology.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. theorized that if one loves their country, they want to see it do and be better. I believe that’s the true definition of patriotism. From public service to military service, fighting for equality and supporting national security here and abroad, Black Americans have more than demonstrated their love for the US. I think collectively many just hope that one day it will be reciprocated.

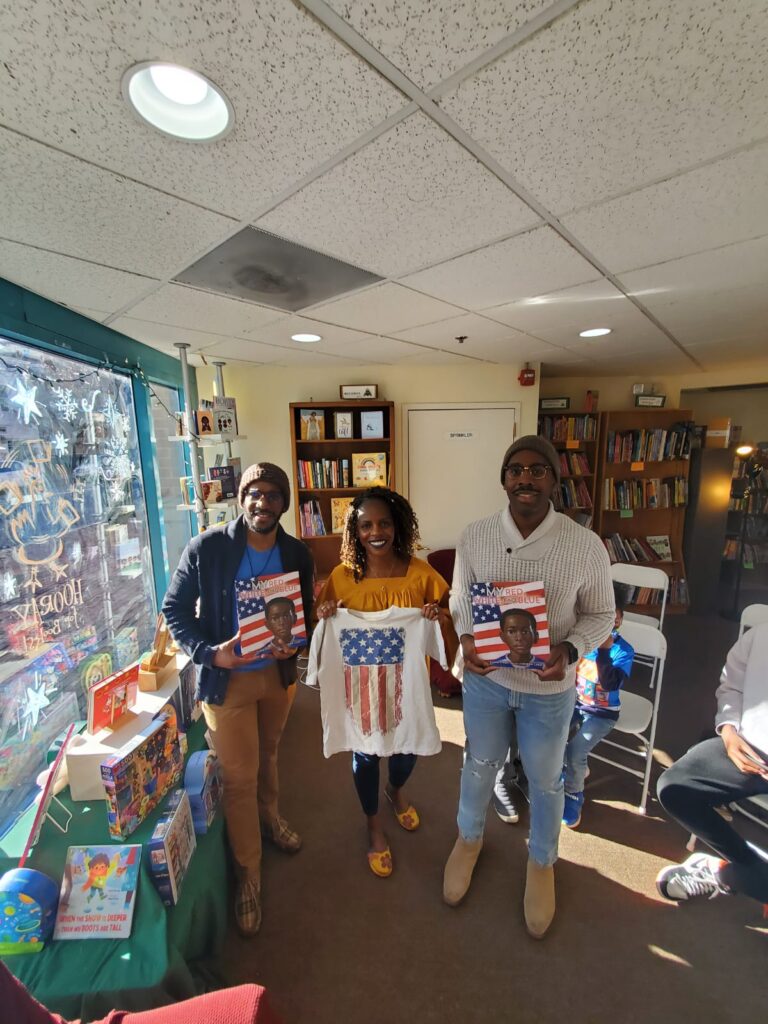

Meet the author

Alana Tyson received her bachelor of science degree from Brooklyn College and her master of arts degree from the University of Maryland. After working in journalism for a short while, she began a career in national security and began to pursue a more creative path as a writer. A winner of the Lee & Low New Voices Award, she lives in Washington, DC, with her family. You can visit Alana online at booksbyalana.com or follow her on Twitter @alanatys and on Instagram @alanathewriter.

About My Red, White, and Blue by Alana Tyson, London Ladd (Illustrator)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

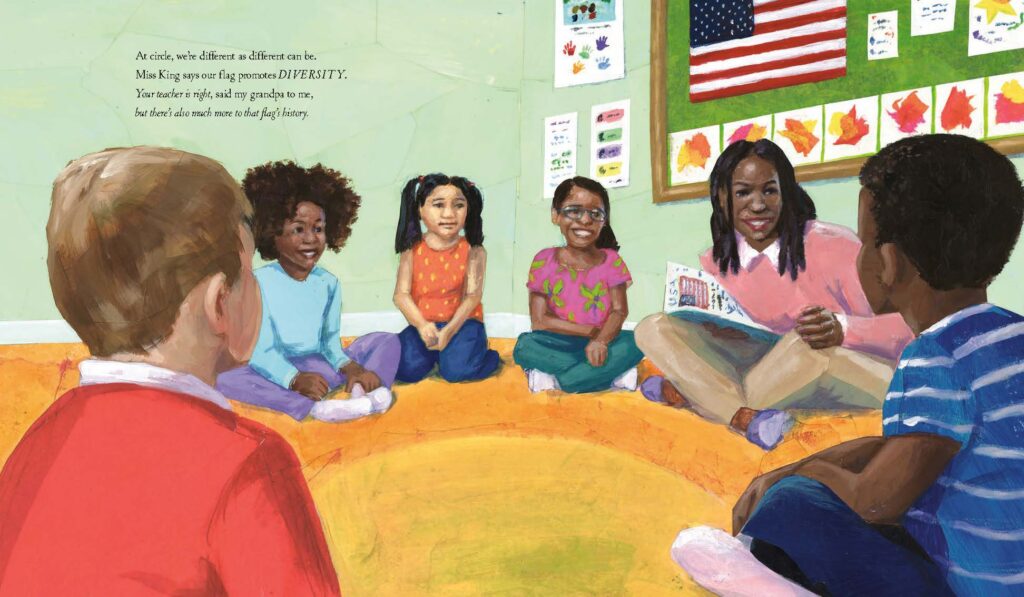

A powerful story about the mixture of pride and pain that one Black family finds in the American flag, and an invitation for each of us to choose how we relate to America, its history, and the flag that means so many things to so many people.

What does the American flag mean to you?

For some, it’s a vision of hope and opportunity. For others, it represents pain and loss. And for many, it’s more complicated than that—a symbol of a nation where the basic ideas of freedom and equality are still up for debate.

From slavery and segregation through Rosa Parks and Barack Obama, the history of Black people in America is a mixture of pride and pain. And while the flag might mean different things to different people, with some choosing to kneel and others to salute, ultimately, it is up to each of us to decide: the American flag is ours to see and relate to as we choose.

In this powerfully validating story that showcases many facets of Black American history through the eyes of a young Black boy in conversation with his grandfather, we are all invited to choose how to relate to America, and to the flag that means so many things to so many people.

ISBN-13: 9780593525708

Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

Publication date: 01/17/2023

Age Range: 4 – 8 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Coretta Scott King Winners

The Ultimate Love Letter to the King of Fruits: We’re Talking Mango Memories with Sita Singh

Double Booking | This Week’s Comics

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT