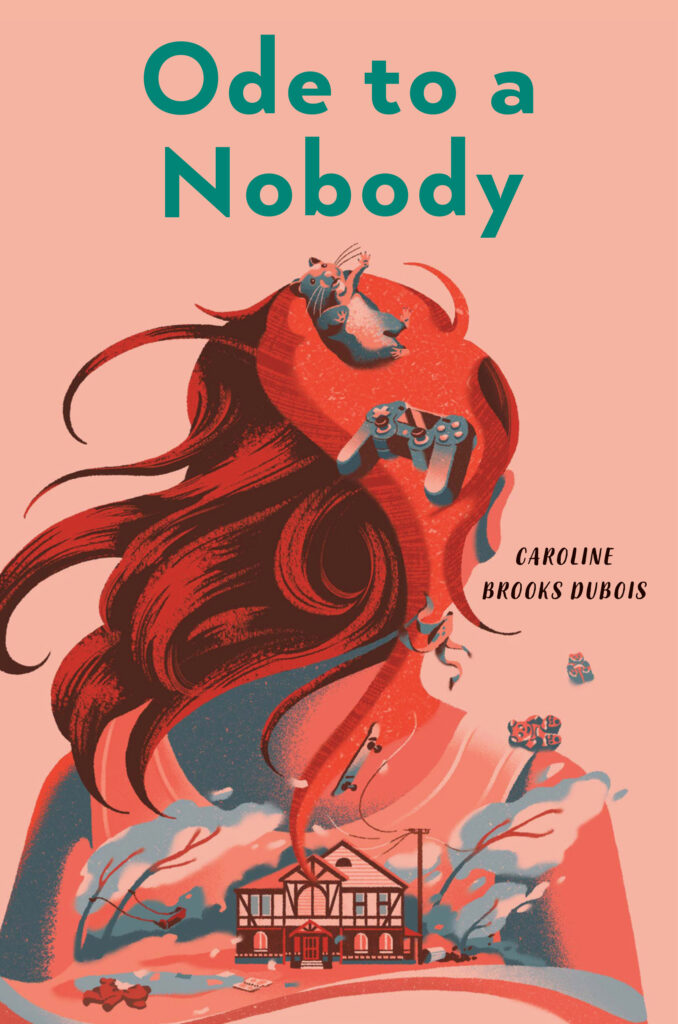

Tragically Playful: How Verse Novels Lend Levity to the Difficult, a guest post by Caroline Brooks DuBois

Call to mind a favorite line of poetry. What do you love about it? The surprising phrasing, the pleasing sounds, the heart-stopping imagery—or something more squirrely to define?

A line of poetry, often composed of only a handful of words, has the potential to contain so much of life, just as a drop of blood holds red and white blood cells, platelets, and plasma. Not to be melodramatic—oh, what the heck, it’s poetry—a single line of poetry can cradle the DNA of life experiences in a way that inspires tears, awe, laughter, and even hope and healing.

Consider such oft-quoted lines as, “Hope is the thing with feathers / That perches in the soul,” by Emily Dickinson, or “Tell me, what is it you plan to do / with your one wild and precious life?” by Mary Oliver, or “I rise / I rise / I rise,” by Maya Angelou, or even “Do not go gentle into that good night. / Rage, rage against the dying of the light,” by Dylan Thomas. Such lines are T-shirt-worthy and frameable because they are in tune with the heartbeat.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Since the 1990s, novels written in poetry have been growing in popularity for young readers, with notable early ones from Karen Hesse, Virginia Euwer Wolff, and Ellen Hopkins. Verse novels can deftly tell a story of trauma, struggle, or loss, while allowing rays of sunshine in and the music of hope to sing.

Not to say non-verse novels don’t deal in the same difficult pages of life, they do, but verse novels have a unique way of resonating around tough topics, and many young readers have decided narratives told in verse work for them. If you asked a young reader if it’s because of the plentiful white spaces, the musicality of the verse, or the playfulness and experimental nature of the words on the page—among other subjective and emotive aspects—they might just roll their eyes, or say, “Yeah. All that.”

All That

Many verse novels specialize in telling stories set in the backdrop of trauma. My own two verse novels are no exception. The Places We Sleep (Holiday House, 2020) is 12-year-old Abbey’s story. Abbey is the new kid at her school in a small southern town, where her father is stationed in the Army, and Abbey’s aunt works in the Twin Towers in NYC. The story opens on 9/11/2001, the day 19 militants associated with al-Qaeda, an Islamic extremist group, hijacked airplanes and used them as weapons against targets in the United States.

Ode to a Nobody (Holiday House 2022) is 13-year-old Quinn’s story, and takes place before, during, and after a devastating tornado strikes her community. It’s based on an EF3 tornado that struck East Nashville, Tennessee, and was, at the time, one of the costliest in U.S. history.

Verse novels have been known to tackle subjects such as life in the dust bowl, teen pregnancy, immigration, gun violence, human trafficking, the aftermath of a flood, addiction, all while depicting the daily life of a middle- or high-schooler.

The White Spaces

In a non-verse novel, words march from margin to margin, with spaces between words, sentences, paragraphs, and chapters. A quick glance reveals that the white spaces in verse novels are greater, like breaths, or transitions in scene or shifts in time, steering the pacing.

Perhaps young readers need more white spaces than they did in a prior century. In just the past few years, they’ve experienced a pandemic; gun violence and mass shootings; racial injustices, unrest, and riots; localized severe weather events; a contentious political environment; and the war in the Ukraine. Witnessing a character forge a path forward in the safety of a book may help readers process the current challenging times. And the white spaces allow readers to catch their breath, since to pause is to process. Metaphorically speaking, if the poems are the bones and the white spaces are the connective tissues holding the narrative together thematically and plot-wise, then readers use the white spaces to infer, interpret, and connect.

In this passage of Ode to a Nobody, note the white spaces, as protagonist Quinn contemplates the trees outside her house before a deadly tornado strikes her community:

Trees are just there.

Like birds. Like air.

Except this one,

snuggled up close

to my house,

its branches stretching

and reaching

and

tap

tap

tapping

its tree fingers

against my pane

Readers are given the space to listen and be in the moment, while processing the play on words and perhaps Quinn’s melancholy, as her parents fight downstairs.

In Skila Brown’s To Stay Alive: Mary Ann Graves and the Tragic Journey of the Donner Party, readers feel the movement of the wagon trains in lines of verse that span the page with “When we can, we spread out / our wagon train, / wide, wide, wide, / move in a line, stretched side to side….” There are generous spaces between the ‘wides,’ so the reader can see the scene.

With fewer expositional moments in verse novels, readers participate actively in the experiential moments of the wide-open white spaces.

Musicality

From the dawn of time, songs have been sung for nurturing, healing, inspiring, and celebrating. And since poetry is sibling to song, it’s this very musicality that can sometimes be felt in a verse novel. They’re popular read-louds in classrooms, likely due to the pleasing sound devices, such as rhyme, repetition, onomatopoeia, assonance, alliteration, and consonance, among others.

In Reem Faruqi’s Unsettled, Nurah’s family must move from Pakistan to settle in the United States, and she misses what she’s left behind: “Back home / the weather is / hot hot hot. / But in the evenings / when the sun gets sleepy / it gets cooler / balmy / and/ breezy.”

Verse novels, also, capture the prosody and cadences of speech, and because they pare down to essential dialogue, they can emulate the nuances that live authentically in spoken exchanges. Of course, some lines are also just fun on the tongue when the music marries the meaning.

Immediately after the tornado in Ode to a Nobody, the accumulation of alliteration and assonance creates a sticky invading dampness for Quinn and her mom:

When we move

together from our spot,

we notice the air—thick

and moist, like the outdoors

has been invited in.

Few windowpanes remain,

and puddles of rain

pool here and there.

The subtle music entices the ears and heart to feel spectrums of emotion like shock and relief.

The Playfulness

It might seem odd to couple playfulness with difficult topics, but maybe that’s the point. Verse lends levity. The fact is—poetry has been known to play, even at its most woeful, just as a child will once again play after weeping. This essence mimics the resilience and innocence of childhood. For some, verse novels might even churn up nostalgia for the songs and nursery rhymes of infancy. Because, as we know, play and its friend laughter can host a cathartic good romp.

Poetry has a full toybox of ways to play, but one obvious method is through form, including line length and breaks, spacing, and the visual shape or concrete nature of poems on the page. The form can be whimsical or experimental, it can capture the meaning, it can be the meaning. Playful moves with form can add interest, whimsy, engagement, and lightness, allowing readers to imbue meaning on several levels: intellectually through the sounds and words and visually through the ‘picture’ of the poem.

Consider Jason Reynolds’ Long Way Down, where the poems literally—and playfully—track down the page, like an elevator ride down. The use of enjambment and caesura give the reader a feeling of movement and anticipation in the harrowing story.

In Ode to a Nobody, Quinn embraces poetry in the storm’s aftermath and writes through the perspective of the tornado, the words spiraling tornadic across the spread:

Houses, barns, swing sets, cars—these are my playthings

I pick one up, catapult it,

snatch another, break it, smash it, snap it,

snag a person from a couch and flop them like a doll

So, Why Verse?

Verse novels grapple so proficiently with the difficult because the nature of poetry is to feel—to feel intensely, immediately, and experientially. Poetry is about showing, healing, aiding, soothing, inspiring, motivating, cheering, galvanizing, and many other -ings. The verse, in a sense, ‘tames’ the tragic through white space, music, and play. Poetry can mirror life, turning the reader from tears to smile to a hopeful and pounding heart all in one line. If a poem were a body, it would have two hands. In one, it would hold joy, surprise, laughter, tenderness, and hope. In the other, sorrow, tragedy, tears, shock, and despair. And when the fingers weave together, there is a moment of delicate beauty and balance—just as in life.

Meet the author

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Caroline Brooks DuBois received her MFA in poetry at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, under the scholarship of Pulitzer Prize-winning poet James Tate, among other greats in the poetry world. Caroline’s debut novel, The Places We Sleep (Holiday House 2020), is an NCTE Notable Book in Poetry and A Bank Street Best Children’s Book of the Year and received a Starred Review from School Library Journal. Her second novel, Ode to a Nobody, publishes 12/6/2022 (Holiday House) and has received a Starred Review from Publishers Weekly. Caroline is the director of the Literary Arts Conservatory at Nashville School of the Arts High School in Nashville, Tennessee, where she lives with her singer-songwriter husband, with whom she’s co-written songs, and their two children and dog.

Website: Caroline Brooks DuBois

IG and Twitter: @carolinebdubois

About Ode to a Nobody

A devastating tornado tears apart more than just houses in this striking novel in verse about a girl rebuilding herself.

Before the storm, thirteen-year-old Quinn was happy flying under the radar. She was average. Unremarkable. Always looking for an escape from her house, where her bickering parents fawned over her genius big brother.

Inside our broken home / we didn’t know how broken / the world outside was.

But after the storm, Quinn can’t seem to go back to average. Her friends weren’t affected by the tornado in the same way. To them, the storm left behind a playground of abandoned houses and distracted adults. As Quinn struggles to find stability in the tornado’s aftermath, she must choose: between homes, friendships, and versions of herself.

Nothing that was mine / yesterday is mine today.

Told in rich, spectacular verse, Caroline Brooks DuBois crafts a powerful story of redemption as Quinn makes her way from Before to After. There’s nothing average about the world Quinn wakes up to after the storm; maybe there’s nothing average about her, either. This emotional coming-of-age journey for middle grade readers proves that it’s never too late to be the person you want to be.

ISBN-13: 9780823451562

Publisher: Holiday House

Publication date: 12/06/2022

Age Range: 8 – 12 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Top 10 Posts of 2024: #8

31 Days, 31 Lists: 2024 Science and Nature Books for Kids

The Sweetness Between Us | Review

The Seven Bills That Will Safeguard the Future of School Librarianship

ADVERTISEMENT