The Red Tuck, a guest post by Harper Glenn

THE RED TUCK is a creative non-fiction short story depicting Harper Glenn’s childhood self-discovery of non-binarism. It unearths how the void of non-representation in their community inspired them to create BIPOC and LGBTQIA-centered fictional narratives.

December 1984 was special. I was four. I can’t remember the exact day. But I remember that morning like brown skin synchs to white bones. Eggs, bacon, cheese grits and crispy toast filled the air. It was the beginning of winter—my cheeks were hot like summer. I wiped the sweat off my forehead, removed white sheets covering my sweaty body, and sat up in bed. It was cold outside, but those white sheets stuck to sweaty brown skin because as per-usual, Grandma had the house on Hell. That’s not an exaggeration. Year round, Winter, Spring, Summer, Fall, Grandma Hattie kept the heater between 75-85 degrees Celsius.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Even though grandma’s house was a desert. I didn’t have to climb the gigantic Magnolia to know it was cold out. One room over, my grandfather was watching the news in the den—I overheard the weatherman say the Sun would rest between clouds, and black ice plagued slippery paved streets. But it didn’t matter. Bad weather wouldn’t ruin that day.

The night before, my mother said in the morning, we’d take the bus to H.L. Greens, pick out my Christmas gift. Christmas was two weeks away, but that’s how it went down in our house. Once I asked why we never waited til Christmas to unwrap gifts. My mom said, “If you need clothes and shoes now… if you want the toy now, you should have them, now. Life’s short. We never know how long we’ll be here. Or if we’ll make it to Christmas.”

My mom was unfiltered and real. I knew Santa wasn’t real in pull-ups. She told her kids while young that she worked hard for every gift she bought, including Christmas gifts; and if a strange white man, or any man in a red suit Ho, Ho, Ho’d down her chimney, she would’ve killed him. Then she’d smile and speak. “I’m Santa Clause. What do you want?”

At four, sometimes, I hated dresses. And when I hated dresses, the hate was visceral. And when it was visceral, dresses made my skin crawl; made me feel foreign—like an alien on earth congregating with humans. I didn’t understand, why if everyone said girls wore dresses, why’d I feel like an imposter inside them, and other times, it’d feel like home. I was too young to have the words to express what I felt, but I knew I was different.

Excited about our trip to H.L Greens, my mom dressed me in my favorite outfit. Red corduroys and a white turtleneck. After sliding tiny feet into high top Puma’s, Mom and I went to kitchen where grandma fixed plates and served OJ while humming negro spirituals.

After gobbling down peppered scrambled eggs, hickory bacon, and cheese grits til our pot bellies rejected food. We got up from the table, put dirty dishes in the sink, kissed Grandma on the mouth, and prepared to leave. I shoved scrawny arms down a thick blue winter jacket, and Mom and I walked to the bus stop at the end of our street. We stood side-by-side in cold weather waiting for the bus to come. I lifted my chin to the sky, staring at Mom, excited about my future Christmas gift that was unknown and unowned.

Fifteen minutes later, the bus arrived. Brown tiny fingers tucked inside my mom’s gentle palm, we lifted our boney knees, and climbed three mechanical stairs. At the top of the stairs, the bus driver smiled and nodded. Mom smiled back, and inserted twenty-five cents, our round-trip bus fare into the meter. I inhaled, took in the smell of too many perfumes, baby milk, baby powder, and old tar. When Mom’s bus fare hit the bottom of the meter, the bus driver pulled a lever and the large bus doors swished closed.

As we scanned for a seat in the front of the bus, I remembered a story my mother told—a memory of the time she gave her seat to an old white woman. When I asked her why, she said kindness doesn’t have a color. Said she didn’t have to get up but gave the old woman her seat because she could stand and hold onto the rail better than the old white woman could. That in that moment, she didn’t color. She saw an old woman who needed help.

Moments later, mom spotted the last double-seat near the front of the bus. She instructed I take the seat by the window. That it wasn’t safe for little kids to sit in aisle seats. Said dangerous things could happened: Said the bus could stop come to a sudden stop. If that happened, she didn’t want me flying out of the seat, that she wanted to protect me.

As the bus moved, I stare out the window sucking the life out of my right thumb. Riding the bus was always an adventure—I’d play games peering out the bus window: solo version of Punch Buggy No Punch Back—a game I’d play with cousins, in which we’d punch each other in the arm wherever we saw a VW bug or raggedy car. Instead of punching someone, I’d pinch my forearm. Whenever the bus rode pass houses, I’d watch kids ride bikes, hop off bikes, and run to the back of buildings and houses. I wondered if the back of those houses turned into a game of hide-go-get-it—a game resembling hide and seek, except the seeker stole kisses from the hider.

But often, riding buses was like watching parades. I’d look down at small cars, big trucks, and folks driving them, waving at them like I was someone special—a king or queen on massive royal float. True, I wasn’t king or queen, but that didn’t stop me from imagining the royal suits. Cause back home, I was a four-year-old drag king. I’d try on Grandaddy’s fedoras, shoes, coats, and ties, then model grandma’s fancy church hats. Sunday mornings, I’d watch granddaddy Magic Shave his head and beard. And once grandpa left the bathroom, I’d lock the door, spread coco butter around my jaw, pretend-shave the invisible beard under my neck with a wooden brush handle.

One stop away from H.L Greens, Mom said I could ring the bell, because she knew every kid riding the bus wanted to do it—the privilege to pull the white string alerting the driver to pump the breaks at the next stop. I pulled the string. And when the wheels on the bus screeched and the bus stopped, Mom took my hand. We stood, walked to the front of the bus, and got off the bus downtown, Augusta, Georgia, one block from H.L Greens.

As a kid, I didn’t realize it, but being raised in Augusta, Georgia was pretty-fucking-cool. It’s where my grandaddy brought sugar cane home, carve the tip of the bark with a pocketknife, and served pieces to my siblings. My cousins and I’d run barefoot on roads made of red clay. My grandma had pecan tree in the front yard, a peach tree in the back yard, and our neighbor had chickens my friends chased. But Augusta was bigger than my childhood memories.

Downtown Augusta was the entertainment Centre. It’s where the late James Brown, The Godfather of Soul, lived and threw block parties with free food and hosted the annual Turkey Giveaway every November. It’s the home of my late uncle, a well-known gospel singer, Little Johnny Jones. Uncle Johnny was the lead singer in The Swanee Quintet, and briefly, Sam Cooke’s replacement with The Soul Stirrers.

Like any town, Augusta wasn’t without a troubled past. On the short walk to H.L Greens, Mom said downtown 9th street is where most black folks shopped in black owned businesses. Said at one-point, black people were only allowed to walk down one side of the street. And white folks strolled the other. She told me about The Lenox Theatre—the black people theatre, where Coca Cola bottle tops were currency to buy movie tickets. She smiled and chuckled reliving the time she saw Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner at The Miller Theatre—the cinema with white only signs. Said when black folks saw films there, it required they sit in box seats, the mezzanine level, high and far away from white folks. Said black movie goers didn’t like the separation so they’d throw spit balls into the audience from box seats.

Five minutes after hopping off the bus, Mom and I reached H.L Greens Department store. Opening the doors to H.L Greens during Christmas season, was like entering this magical place filled with anything you could possibly need. Once inside, I inhaled. It smelt like new car, cinnamon, and peppermint.

The department store was set up in sections. Racks of clothes filled the front of the store. I remember walking slow, touching pants on hangers with eager eyes and empty pockets. Situated in the middle of the store were groceries. The back store was filled with toys. I followed my mom to the back, where she stopped down the aisle to the area labeled Girls. But I didn’t wanna stop. At four I was head strung and curious, determined to find my Christmas gift.

To find the perfect toy, I went up and down the toy isles, playing everything: The Teddy Ruxpin storytelling bear, I pressed play on the fully operated test toy and listened to Teddy tells tales. Played battle with green G.I Joe figurines. Touched Star Wars characters through hard plastic packaging. Fed a cabbage patch doll fake milk from a fake bottle. I touched Barbie and Ken boxes, wondered why Barbie didn’t have red corduroys like me, and wanted to slide Ken into one of Barbies pink gowns.

I returned to my mom’s side. While she scanned shelves of girl perceived things. I walked down the same aisle, stopped in the toy section labeled Boys. In the boy’s section, I stood amazed in the middle of the aisle. Chin facing the ceiling, I was fascinated by everything.

On the enormous three-tier shelf before me was stocked with board games, basketballs, soccer balls, footballs, bats, Legos, plastic fireman hard hats. Though all the toys were cool. Nothing compared to the feeling I’d felt when I saw it. I got down on both knees, touched it, then removed it from the bottom tier.

It was a beautiful plastic machine. Crimson red—four windows, two operational doors. It stood tall on four thick hard black rubber wheels. I smelled the inside of the car—its black leather seats smelt like newspaper.

Floor dust painted the kneecaps of my red corduroy pants white. With firm hands over the roof of the red truck, I pushed it up and down, and back and forth in the middle of the aisle. It wasn’t long before Mom left the girls section of the aisle to join me.

When Mom reached me, I was on my knees, spinnin’ around in circles. She knew I wanted the red truck because seconds after she’d arrived, she said, “You can’t get that. It’s not for little girls. That’s for boys.” She held the little doll she had in her hands, and continued, “See? This is for little girls.”

With pouty lips, I mean mugged my mom and said, “I wanna tuck!”

“You can’t have that truck. It’s not for you,” Mom said.

Four-year-old me wouldn’t accept mom’s response. I remember thinking if trucks were things only boys could get, I didn’t wanna be a girl. It wasn’t’ fair I couldn’t play with toys I liked because of who I was. I ignored my mother response. I yelled louder. “I wanna tuck!”

Mom wouldn’t budge.

At the time, she couldn’t fathom buying her daughter a red truck, but didn’t want to buy the doll I didn’t want. As a comprise, she bought the Chatter Phone Pull Toy—a rotary phone with a red handset and red wheels. I got the wheels I wanted. My mom got the satisfaction of buying a toy I loved, even though it wasn’t the toy I originally wanted. It was the in-between toy. I loved that phone.

Over the years, whenever my mother tells this story, she remembers wanting to buy me something special that Christmas. Said she wanted to buy a pretty, brown doll, but back then, in the early 80’s, there weren’t many dolls of color, let alone black ones. She said while I was playing with the red truck in the middle of the aisle, she smiled, excited thinking I’d like the doll in her hands better than the truck. But when she presented the doll, and asked if I liked it, I said no. But that’s not all.

Whenever my mom thinks of trying to take the red truck away, she chuckles—remembers how I held on tight, wouldn’t let her take it. Said she was shocked when I yelled. “I wanna tuck!” Said the more she tried to move my hands off the roof of the truck, the madder I became, the more I scrunched my nose, and the louder I screamed. “I wanna tuck!”

It’s been decades since I uttered those three words. “I wanna tuck.”

Being African American in the south was rough. Being open and queer was isolating. And being a black, non-binary, xx-chromosome human, who at times felt genderless was terrifying. In my mind, becoming a writer was the path to ease the terror.

I thought one day, I’ll grow up, and write books with brown faces in them. But I wouldn’t stop there. I’d make sure those brown faces lived in worlds surrounded by every race and gender identity. And in doing this, I’d explore the beautiful complexities of my own layered identity though interchangeable POV’s, character arcs, emotions, family dynamics, and colorful settings.

Like every writer with hopes of writing and publishing books, I had fears. I have fears. Those fears scream, “What if people don’t see themselves in my book(s)? —what if I don’t get it right?” Well, I might not always get it right, folks. And that’s okay. No one’s immune from imperfection. But maybe not getting it right will inspire creativity; like not seeing my brown skin in classics I loved, inspired me.

If I close my eyes tight, I see them, see me. It’s 1984. I’m the adult I am today, standing next to that little enby in red corduroys, in the heart of Downtown Augusta Georgia, kneeling in H.L. Greens, yelling, “I Wanna Tuck!” I’d kneel beside me, whisper it’s okay. Tell myself that one day, you won’t feel foreign inside your skin. I’d promise myself, there would come a time where who they are is forever okay—that they’d never have to choose. And that one day, when they’re big and tall, they’d get their Red Tuck.

Meet the author

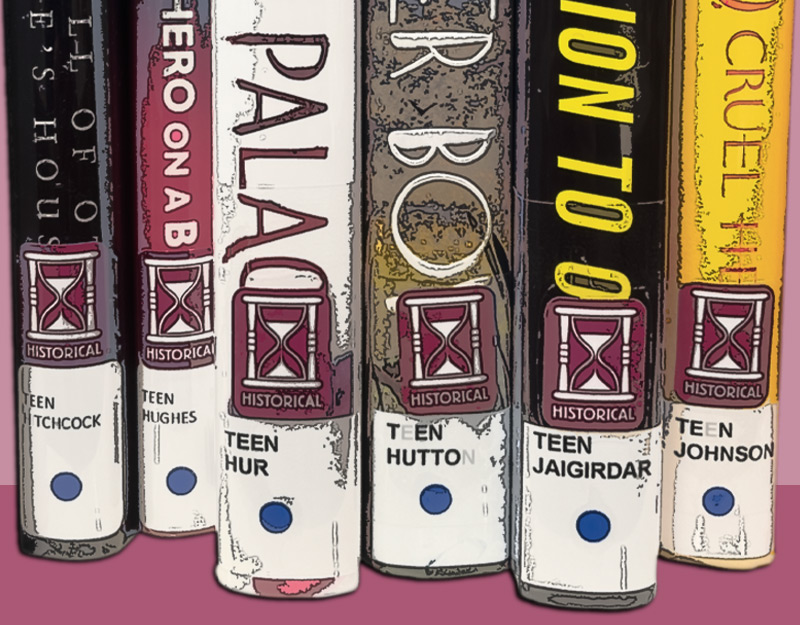

Harper Glenn is an author of fiction. In addition to creating literary works that unveil the psychological, sociological, and economic disparities in poverty-stricken regions around the world, they love vintage books, anatomy, and old cemeteries. Though born and raised in Georgia, Harper resides in Washington State. Harper’s young adult dystopian, MONARCH RISING, debuts w/ Scholastic Press 10.4.22.

Media Links:

Linktree: https://linktr.ee/harperwritesbooks

Website: www.harperwrites.com

Twitter: @harpwrites https://twitter.com/harpwrites

IG: @harperglennwriter https://www.instagram.com/harperglennwriter/

About Monarch Rising

In a chilling near-future New United States of America, Jo Monarch has grown up in the impoverished borderlands of New Georgia. She’s given one chance to change her fate… if she can survive a boy trained to break hearts.

Today is the day Jo Monarch has been wishing on the moon about her entire life. It’s the day of the Lineup, when she could be selected to leave her life in the Ashes behind. The day she could move across the mountains to a glittering, rich future.

Once Jo is plucked from the Lineup, the real test begins. She still needs to impress the New Georgia Reps at tonight’s Gala, and her path forward leads straight to Cove Wells. The damaged stepson of one of the Reps, Cove has been groomed as an emotional weapon, taught that love is a tool — and he’s set on breaking Jo’s heart next.

When a riot breaks out back in the Ashes the night of the Gala, Jo’s dreams might all go up in smoke. Can she really have everything she’s ever wished for… when it means leaving all her loved ones behind in the fire?

Harper Glenn’s debut is as gripping as it is prescient, an unflinching meditation on whether love can save us from ourselves, and what it takes to be born anew.

ISBN-13: 9781338741452

Publisher: Scholastic, Inc.

Publication date: 10/04/2022

Age Range: 14 – 18 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on BlueSky at @amandamacgregor.bsky.social.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The 2025 Ninja Report: It’s Over

Review of the Day: The Black Mambas by Kelly Crull

Ghost Town | Review

30 Contenders? Our Updated Mock Newbery List

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

ADVERTISEMENT