Reforging Creativity, a guest post by Jay Hosler

Imagine a dragon. Let’s say that its scaly hide is a tartan plaid (you can pick the color). Imagine it has an enormous set of handlebars sprouting out of its shoulders so that any giant who decides to ride it has something to hold onto. Can you see it? Great. Now give it big bunny ears so it can hear the cries of its victims better. That is a weird dragon, but you know the strangest thing about it? It has never, ever existed anywhere except in your brain. Right now. How is it possible that the four-pound glob of gray Jell-O between your ears can create and visualize something so totally disconnected from reality? We don’t really know yet, but I suspect the people who eventually figure it out will have harnessed the creative power of science and art.

My day gig is as a neurobiology professor at a small liberal arts college in Pennsylvania, but at night I write and draw graphic novels about the natural world. For most of my adult life I have straddled what many people consider two different worlds: science and the arts. My scientist friends think it is weird and cool that I make art and my artist friends think it is weird and cool that I do science. The assumption is that the two areas are fundamentally different and that bridging them is somehow unique. But is it? Or is that perspective the result of the way we’ve all been taught? Let’s imagine where humans were 15,000-17,000 years ago when the Lascaux cave painting were made.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The Lascaux cave paintings are works of art made by prehistoric people. The feature stunning images that were painted with mineral-based pigments. Readily identifiable species thunder across the walls in mighty herds. The scenes include mythological creatures and a strange bird headed man that hint at imaginative, magical stories. So how do we classify these painting? What pigeonhole do we put them in? Are they art? Natural history? Creative fictional narrative?

Or are they all three at once?

It’s a remarkable thing to contemplate: a time in our history when human creativity wasn’t fractured. When our imaginations stretched continuously across “disciplines.” I think this is how we see the world when we are younger. The homemade experiments of a child are all part of elaborate stories that they tell themselves and which they document with crayon masterpieces. Science, art, and story may seem different to grown-ups, but a child wields them as if they are one, giant creative magic wand. Kids seem to understand intuitively, that science, art, and story all require us to imagine something that has never existed before. They form the creative core that defines what makes humans so interesting. We are at our best when we ignore artificial boundaries and connect ideas from different worlds.

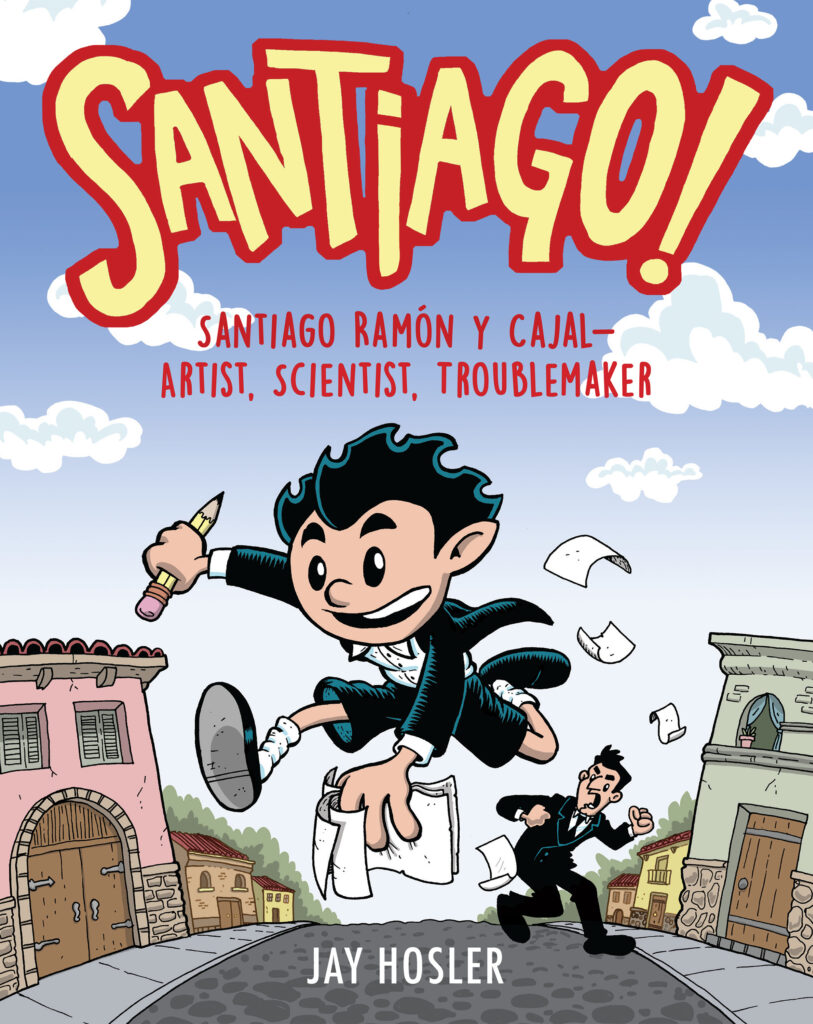

This is the idea I’ve tried to capture in my book Santiago! Santiago! is the story of Santiago Ramon y Cajal, a national hero in Spain and the father of modern neuroscience. As a kid, Santiago wanted to be an artist, but his father said he had to become a doctor. Santiago was denied art materials, but he was undeterred. He found clever ways to secretly extract dyes from common materials and make paint brushes out of wadded up paper. The demands of his art drove him to become a consummate experimentalist and inventor. Unfortunately, his father was unrelenting. Santiago was forced to go to medical school, but the artistic skills he had developed as a child soon opened new doors for him. He became interested in the nervous system and found innovative ways to paint nerve cells and map out the complex connections in the brain. He drew and painted what he saw, and his art revolutionized the way scientists thought about the brain. In 1906, his scientific art helped him win the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

All of that would make for a very good story, but what makes Santiago’s story so compelling is that he attacked life with such unbridled deviltry. He was a first-rate troublemaker who approached is artistic and scientific endeavors with zealous determination. He cleverly escaped the literal and figurative prisons erected by the adults in his life, finding ways to circumvent their attempts to break his spirit and impede his art. There was joy in what he did. The same joy that scientists and artists feel in their creative work.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Cajal is my hero. He took art and science and he reforged them into a single creative endeavor. He helped unlock some of the fundamental mysteries of our dragon-imagining brains with inventive ingenuity and artist flair. His work laid the foundation for how we understand learning and creativity. My hope is that his story resonates with kids as much as it has with me and that they grow-up to imagine news world in very different ways.

Meet the author

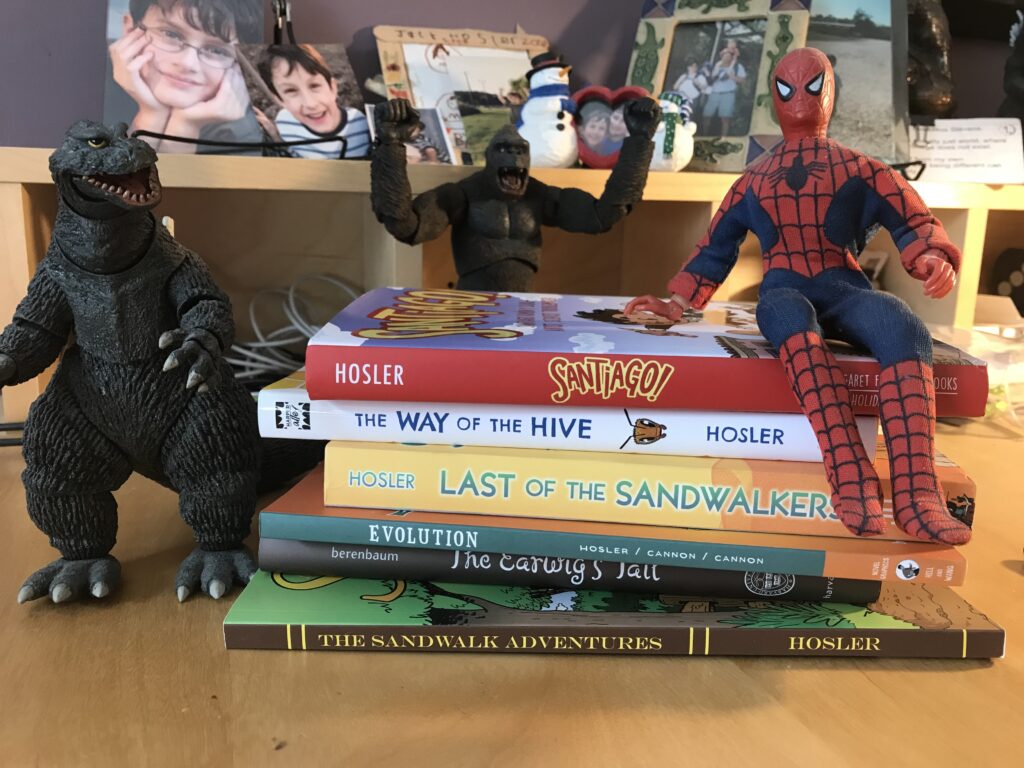

Jay Hosler is a biology professor at Juniata College by day and a scheming cartoonist at night. His diabolical plan is to secretly weave his love of science and the natural world into thrilling tales of adventure and derring-do. So far, the plan is working. Unsuspecting readers fall into stories about creepy-crawly things and discover the wondrous world right underfoot. His books have been translated into several languages, but he can only read the ones in English. In his spare time, Jay likes to read comics and watch Godzilla movies. He lives in Pennsylvania with his queen and two drones.

Links:

Instagram: @hoslerjay

About Santiago!: Santiago Ramon y Cajal!Artist, Scientist, Troublemaker

A graphic novel retelling of the inspiring true story of polymath Santiago Ramón y Cajal, visionary pioneer of modern neuroscience, and his early dreams of becoming an artist.

Based on a true story, Santiago Ramón y Cajal is every child who has struggled to navigate the expectations of adults.

As a young boy, all Santiago wanted to do was be an artist. But his father wanted him to become a doctor, insisting that pursuing art was not a true profession. Although Santiago was forbidden by his parents to make art, Santiago secretly kept at it—making homemade paints and brushes and honing his craftsmanship. He also loved figuring out how things worked and made slingshots for his friends and even a fully functioning (and very dangerous) cannon. Sadly, the one thing he couldn’t figure out was his father.

After years of locking horns, Santiago’s father seemed to win, and Santiago was sent to medical school. As a medical student he discovered the wonders of how animal bodies work, and his studies eventually led him to the microscopic mysteries of the brain. Using the artistic skills he honed as a child, Santiago painted brain cells to unlock their secrets. His pursuit of art had trained him to be observant, persistent, resourceful, and creative in his research. In 1906, he won the Nobel Prize for medicine and is considered the father of modern neuroscience—proving anything is possible, even for a mischief maker.

A Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selection

ISBN-13: 9780823450367

Publisher: Holiday House

Publication date: 10/25/2022

Age Range: 8 – 12 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Happy Poem in Your Pocket Day!

This Q&A is Going Exactly As Planned: A Talk with Tao Nyeu About Her Latest Book

More Geronimo Stilton Graphic Novels Coming from Papercutz | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT