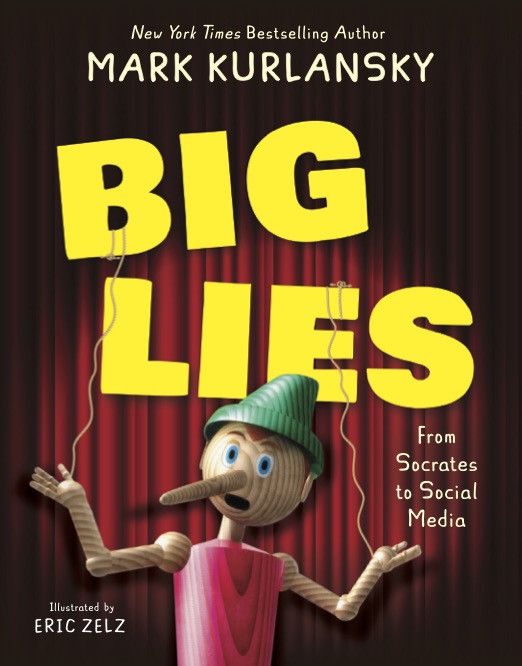

The Tickle of Truth: Why I Wrote BIG LIES, a guest post by Mark Kurlansky

“Truth tickles everyone’s nostrils. The question is, how’s it to be pulled from the heap?”

—Isaac Babel, “My First Goose” (a story in Red Cavalry, 1926)

It is in a writer’s nature to want to communicate ideas, beliefs, and knowledge that readers will accept and maybe even embrace. Usually that’s what I want, too, but not with BIG LIES. One of the greatest dangers in the world today is that people are too willing to accept things without questioning them. So, please, doubt me.

It would be easy just to believe what I lay out in this book, but that would defeat my purpose. Although I have verified the truth of every word through fact-checking and research, I ask you to consider as you read and to decide for yourself what to believe. Francis Bacon, the first practitioner of the scientific method, wrote in 1612, “Read not to contradict and confute, nor to believe and take for granted, nor to find talk and discourse; but to weigh and consider.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

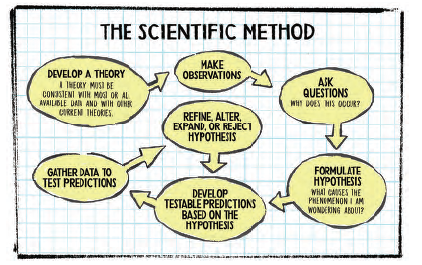

We can learn much from scientists. The scientific method that Bacon promoted does not accept anything without testing it first. I recently met a woman at a book signing who flatly rejected the ideas of Darwin, saying to me, “It’s just one man’s theory.” Darwin would have agreed. He published his theories and invited other scientists to test them. That is how science works. Darwin’s theories have been tested for more than a century and a half now, and they have proven remarkably accurate—but they will go on being tested.

If you prefer a less scientific approach to truth, there is the journalist’s method. When I started reporting for newspapers, the first thing I learned was not to believe anything I was told. A journalist tries to confirm all information through a variety of sources and always considers how much self-interest and prejudice might be in play. This is not to say that you should always believe journalists. Not all of them are honest, careful, and thorough. You have to question journalism in the same way a good journalist questions sources.

You can in time develop a nose for truth. This doesn’t mean you will always know truth by instinct, but you can sometimes smell a lie. When you get that tickling sensation in your nose, you have to sniff deeper.

Questioning things is how we struggle toward the truth, and it is that struggle that keeps the world from descending into chaos.

Some lies are easy to detect but hard to defeat. Donald Trump’s claim that he won the 2020 election was an obvious lie. Every reliable source, including close advisors and family members, told him so. He himself probably knew, but he was providing ammunition for supporters who wanted to believe that he won. Sometimes when a lie seems absurd, you need to understand that you are not the target audience.

When Bongbong Marcos was running for president of the Philippines, he had to defend the infamous kleptocracy of his father, Ferdinand Marcos. He did so by assuring voters that the billions of dollars stashed in offshore accounts during Ferdinand’s two decades in power had been kept for Bongbong’s government to spend on the Filipino poor. It was a lie, but it comforted people who wanted to vote for the ex-dictator’s son.

To excuse his unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, Russian dictator Vladimir Putin claimed that he was rescuing Ukrainians from a Nazi regime. Never mind that Ukraine’s democratically elected regime is led by a Jew, that there is no evidence of Nazis in the government, and that no Ukrainians claim to have suffered Nazi persecution. Putin’s lie is not intended for Ukrainians or the international community, but for Russians who want to justify Russia’s aggression.

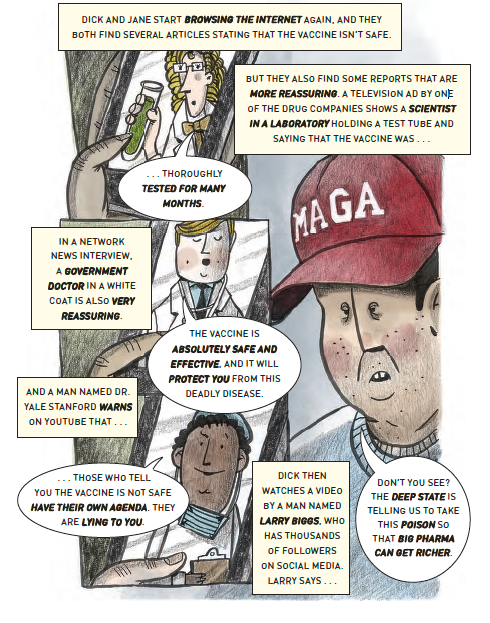

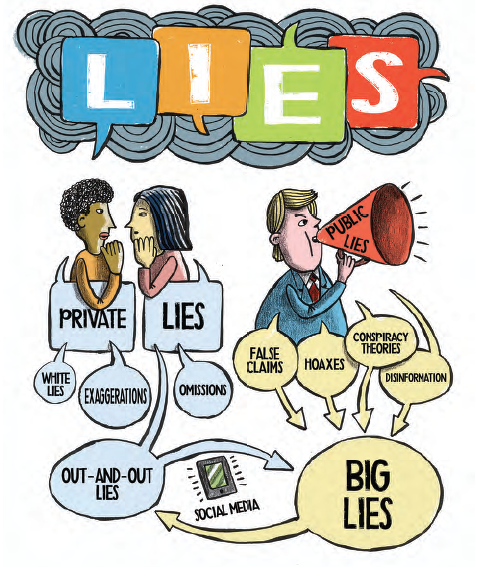

Some lies are laughable—such as extraterrestrial lizards disguised as humans, or Jews causing California forest fires by beaming lasers from outer space—yet even these absurdities find believers. If you tell a lie—any lie, no matter how ridiculous—to a hundred people, probably two or three will believe it. If you can tell it to thousands, you might get a few hundred believers. The problem with social media is that the lie can go out to millions, and then how many believers will there be?

We are told that social-media platforms have made this the age of lying, but every introduction of a new communication medium has led to similar claims. Plato bemoaned the increase of lies when orators were replaced by the written word. Two thousand years later, the manual printing press let lies travel faster, and then the development of engine-powered presses gave lies wings. Radio initiated another new age of lying, and then television outdid radio. Now there are social-media platforms. Of course, we should remember that these media also increase the opportunities to spread truths.

The lies spread by social media aren’t particularly creative. Most are old lies being recycled. What chiefly distinguishes social media is amateurism. Adolf Hitler maintained a huge staff of professional liars to create lies for radio, but anyone can post a lie on Twitter or Facebook.

The object of social media is to attract the most “likes,” friends, or followers, and the more outlandish a lie, the more people it will attract. Donald Trump started his 2016 presidential campaign with fairly moderate tweets promoting himself, but he soon discovered that the more outrageous his tweets, the more followers he amassed.

While it is often easy to spot a lie, it is harder to know what is true. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, a still-admired nineteenth-century German philosopher, maintained that there is always an absolute truth, but it is not always possible to know it. Still, the search for truth must be never-ending. We cannot achieve a well-ordered, healthy society for all the world’s people if we do not keep asking what is true.

No lie becomes a big lie without willing believers. Belief is a choice, and honesty begins in each of us. It is all too human to prefer an attractive lie to an inconvenient truth requiring difficult changes. When a lie provides comfort, consolation, excuses, or permission to do what you’d like to do anyway, who wouldn’t prefer it?

Scientists have clearly demonstrated the consequences of climate change—extreme weather, rising seas, forest fires, a decline in ocean life, the steadily increasing destruction of our planet. To save the Earth, we must drastically change our way of life—but who wants to do that? The easier “solution” is to claim that it’s all a hoax and nothing needs to be done, or to admit that it’s happening but assert that it’s not our fault. Then we can do what we’ve always done and watch the Earth slowly—or not so slowly anymore—disintegrate while we are comforted by our chosen lies.

It is hard work to question everything, but our survival and the survival of democracy depend on moral courage, independent thinking, and fair-mindedness. Is there anything more important? I hope you will keep asking yourself what is true as you read this book and live your life.

Meet the author

Mark Kurlansky’s thirty-five books include four New York Times bestsellers—Cod, Salt, 1968, and The Food of a Younger Land—and have been translated into thirty languages. He has received a James Beard Award for Food Writing, a Bon Appétit American Food and Entertaining Award for Food Writer of the Year, and the Dayton Literary Peace Prize. A former journalist, his storytelling mastery makes his books for young adults—including Big Lies and The World Without Fish—equally appealing to adult audiences. Kurlansky lives in New York City.

About BIG LIES: from Socrates to Social Media

In his new book for young readers Mark Kurlansky’s lens is the art of the “big lie,” a term coined by Adolf Hitler. Kurlansky has written Big Lies: From Socrates to Social Media for the next stewards of our world. It is not only a history but a how-to manual for seeing through big lies and thinking critically.

Mark Kurlansky’s bestselling works of nonfiction view the history of the world through unexpected lenses, including cod, salt, and paper. In this new book for young readers his lens is the art of the big lie. Big lies are told by governments, politicians, and corporations to avoid responsibility, cast blame on the innocent, win elections, disguise intent, create chaos, and gain power and wealth. Big lies are as old as civilization. They corrupt public understanding and discourse, turn science upside down, and reinvent history. They prevent humanity from addressing critical challenges. They perpetuate injustices. They destabilize the world.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

As with his book World Without Fish, Kurlansky has written A History of Big Lies for young readers, the future stewards of our world. It is not only a history but a how-to manual for seeing through big lies and thinking critically. “I hope that you will keep asking yourself what is true as you read this book and live your life,” he entreats readers at the outset. “If the Age of Enlightenment is not to be followed by the Age of Chaos, we have to think for ourselves.”

A History of Big Lies soars across history, alighting on the “noble lies” of Socrates and Plato, Nero blaming Christians for the burning of Rome, the great injustices of the Middle Ages, the big lies of Stalin and Hitler and their terrible consequences, and the reckless lies of contemporary demagogues, which are amplified through social media. Lies against women and Jews are two examples in the long history of “othering” the vulnerable for personal gain. Nor does America escape Kurlansky’s equal-opportunity spotlight.

The modern age has provided ever-more-effective ways of spreading lies, but it has also given us the scientific method, which is the most effective tool for finding what is true. In the book’s final chapter, Kurlansky reveals ways to deconstruct an allegation. Is there credible, testable evidence to support it? If not, suspect a lie. A scientific theory has to be testable, and so does an allegation. Who is the source? Who benefits? Is there a money trail? Especially in the age of social media, critical thinking counters lies and chaos.

“Belief is a choice,” Kurlansky writes, “and honesty begins in each of us. A lack of caring what is true or false is the undoing of democracy. The alternative to truth is a corrupt state in which the loudest voices and most seductive lies confer power and wealth on grifters and oligarchs. We cannot achieve a healthy planet for all the world’s people if we do not keep asking what is true.”

ISBN-13: 9780884489122

Publisher: Tilbury House Publishers

Publication date: 09/27/2022

Age Range: 13 – 18 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

In Memorium: The Great Étienne Delessert Passes Away

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT