Form as Message, a guest post by Amanda Rawson Hill

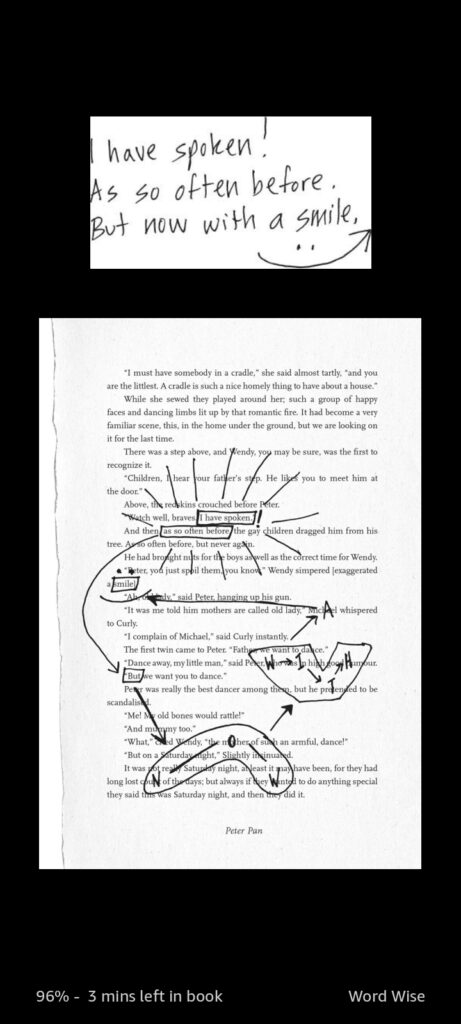

When I first started thinking about the premise for The Hope of Elephants, I had a very specific image in my head. Two identical girls running into a hospital room where they converge into one person sitting in the hospital bed as her blood is drawn. This image came from the recent revelation that my niece had a mutated TP53 gene, meaning she had Li-Fraumeni Syndrome, a genetic condition that leads to very high chances of frequent cancers throughout life.

I wanted to write a story exploring the idea of discovering that you have two possible futures. One the way you always pictured it and the other haunted by cancer. But how should I do it? At first, my thoughts went to something a bit more speculative and Sliding Doors-esque. Dual narratives? Seeing into the future? But as the voice of the main character started talking to me, I had to take a step back. Because she was speaking in free-verse.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

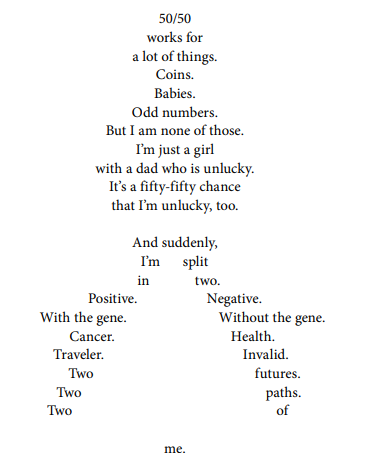

And here was the answer to my conundrum. See, verse novels have this unique ability within non-illustrated literary forms to convey a message both through words, like standard prose novels, but also through visuals. The shape of the words can say just as much, if not more, as the actual words.

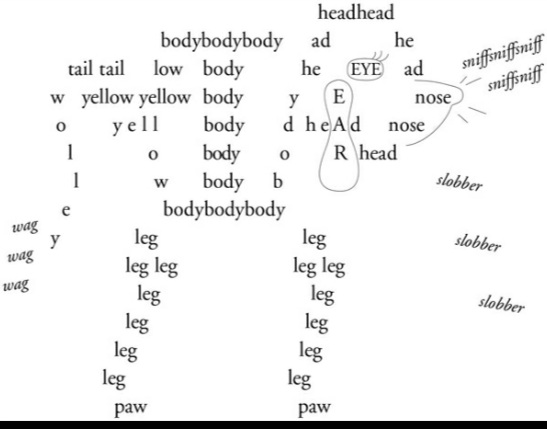

The most basic version of this is the shape poem, employed by Sharon Creech in Love That Dog.

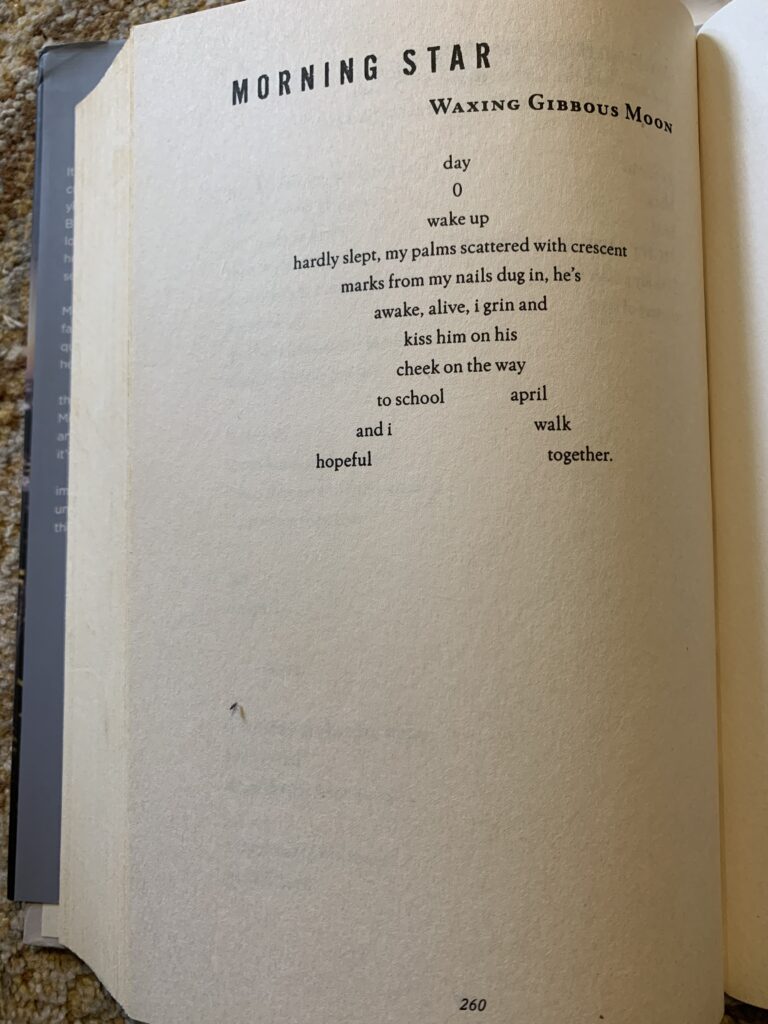

But I really fell in love with the style when I read these poems from Cordelia Jensen’s debut, Skyscraping, in the shape of a full moon. You’ll find many verse novels employing this in small ways, like having the words fall down as they describe a waterfall or going down stairs.

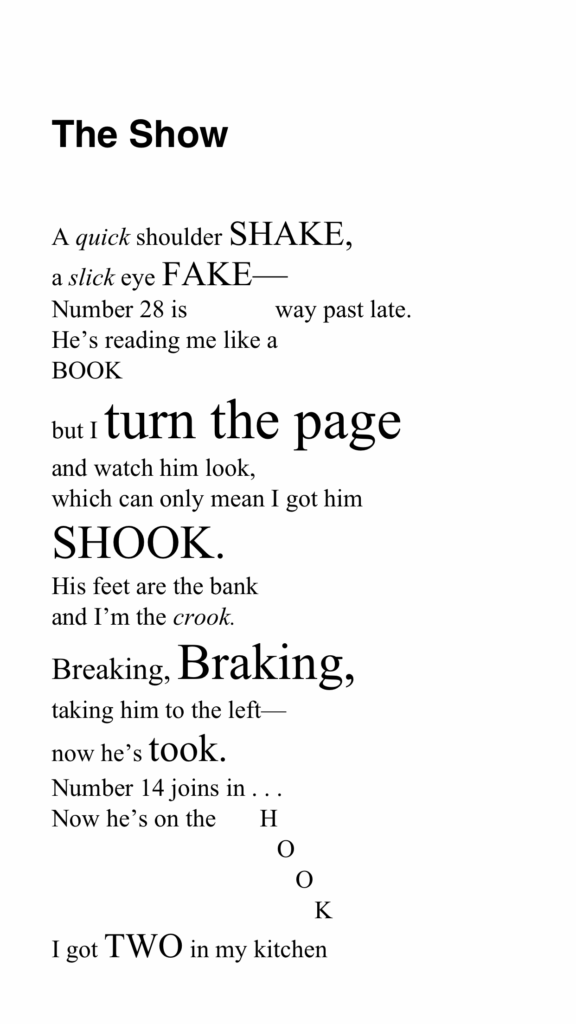

If you are writing a verse novel and want to add more of these small visuals, try to find spots where you are describing something with direction or movement. Shaping your words to reflect the movement and direction goes a long way toward conveying the message. Think about how Kwame Alexander uses both font, size, and direction of words in the opening pages of The Crossover to make the poem so much more than it would have been in just uniform, standard font.

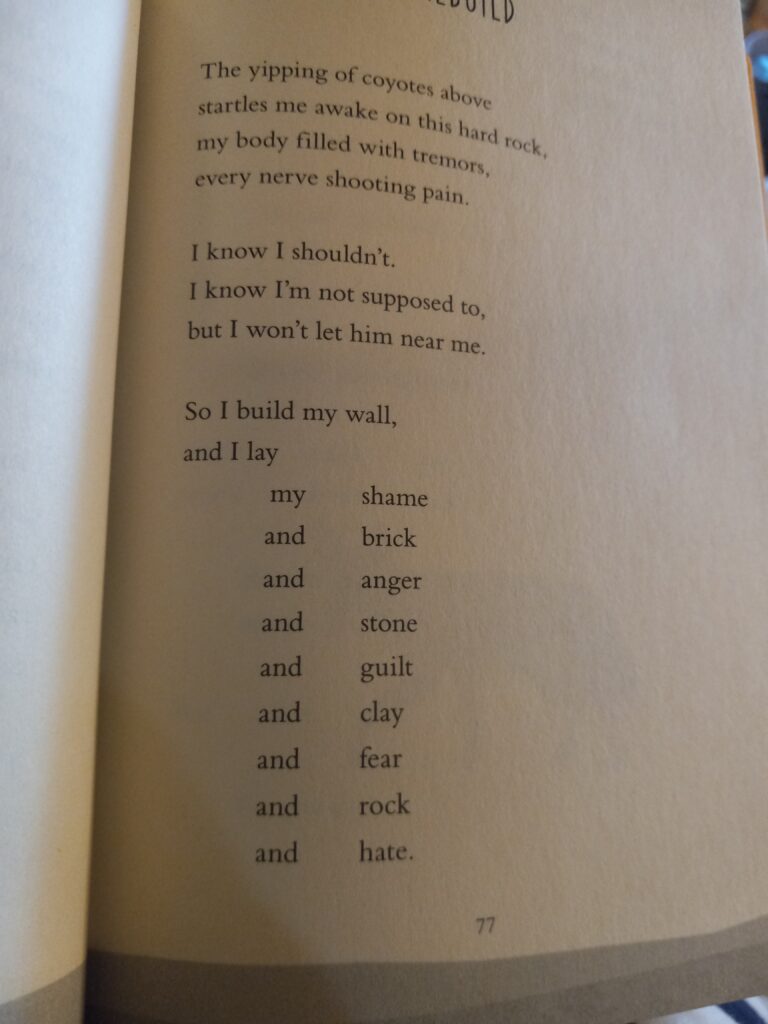

Sometimes poets go even farther than a short visual on a page though. Sometimes, they ask you to dig a little bit deeper into what the spacing of their words is trying to say. I love this example from The Canyon’s Edge by Dusti Bowling. She uses this technique frequently throughout the story, where the words appear to line up like walls. Canyon walls.

In this particular poem, you can see how her hopes and fears are closing in around her like the narrowing walls of a slot canyon. She never has to say that. You know it just by the shape of the poem.

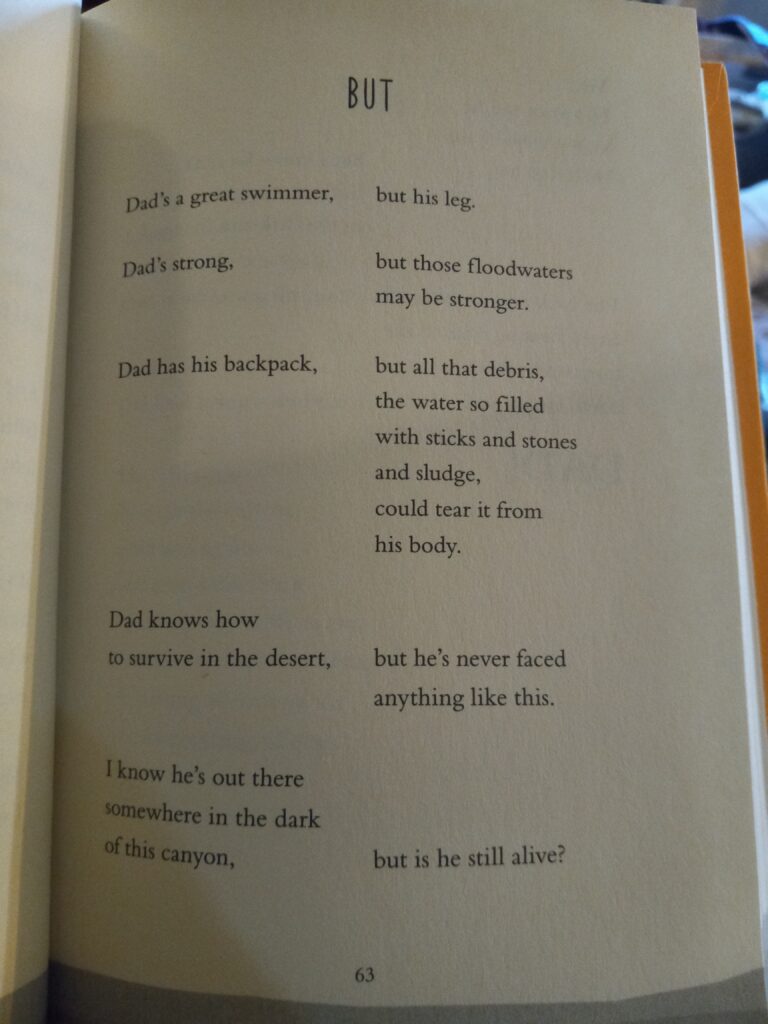

Likewise, in Blood Water Paint by Joy McCullough, this poem directly after Artemisia’s sexual assault is written in a way that says, beyond what the words are saying, that Artemisia is scattered and shaken. Reading the words in this way automatically makes the reader feel off kilter, unbalanced, and a bit panicky, without any of those words or their synonyms being used.

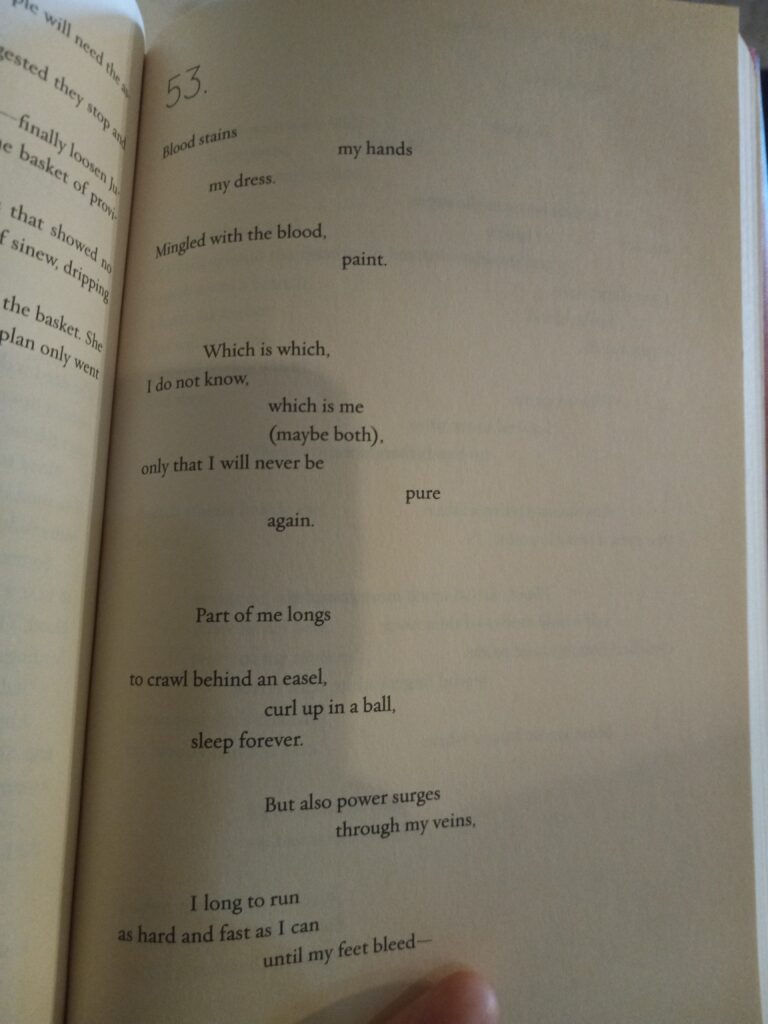

Another master of this kind of messaging through form is K.A. Holt, except I would argue she even goes a step further and chooses actual poetic forms to convey a message. For example, in Rhyme Schemer, the main character learns about black-out poetry. Why is this meaningful? Because the book is very much about there being more beneath the surface of a person. That you can’t know what’s going on in their life. The same way black-out poetry finds a poem in a seemingly boring page of text, we find goodness in a seemingly “bad kid.”

If you want to employ a more broad scale form as message like this, it helps to have an image or symbol in mind and to find ways to return to it and have certain poems reflect that. Is there an image that reflects your theme? Can you reflect that image in the form of some of your poems?

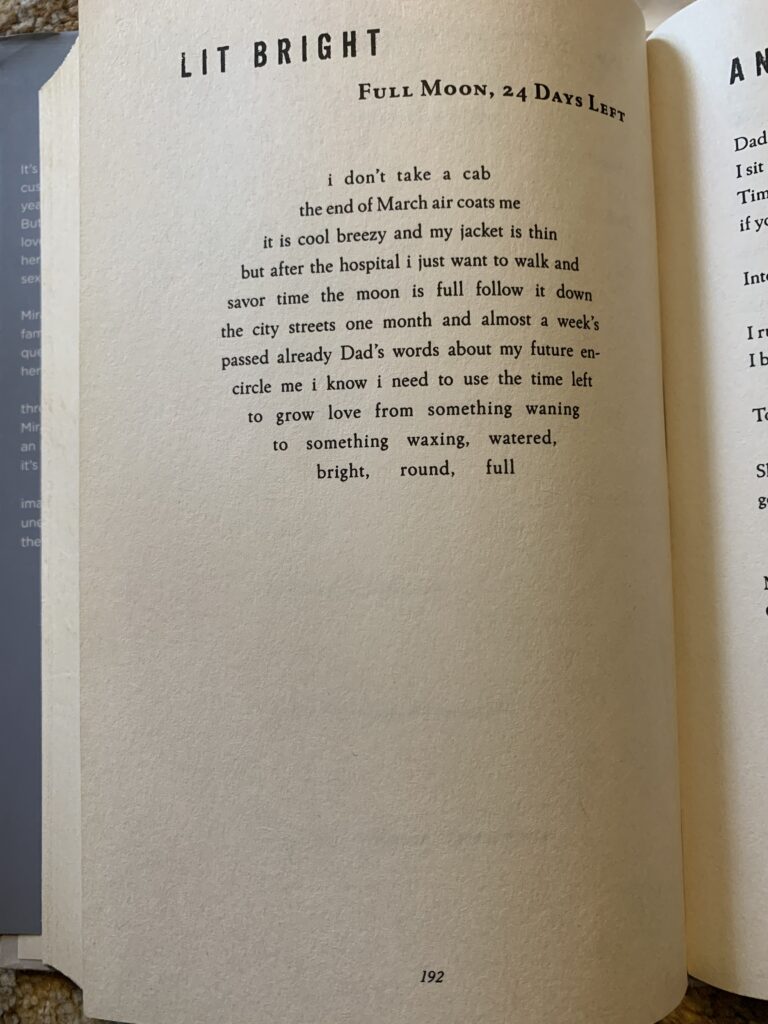

In The Hope of Elephants, I was able to illustrate this idea of being split in two simply through how words were justified on the page. Without ever having to say anything, it becomes an automatic cue to the reader throughout the book, when the right and left justification comes into play, that my main character is viewing the world from the two different sides of herself. And the whole idea behind this format is introduced in this poem, designed to look like strand of DNA, unraveling at one end. And thus, my conundrum from earlier was solved without having to belabor the point in words.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

This is something I love about verse novels. They are so visual. I love to hear them read, especially by the author, but I’m not sure you can ever replace the experience of seeing the way the words form the poems on the page. What other verse novels do you love that create message through form?

Meet the author

Amanda Rawson Hill grew up in Southwest Wyoming with a library right out her back gate. She earned a bachelor’s degree in Chemistry, which she has since put to good use by writing books that make you cry. Her upcoming novel-in-verse, The Hope of Elephants, is a Junior Library Guild Selection. She is also the author of The Three Rules of Everyday Magic, You’ll Find Me, and My Pet Cloud. In her spare time, Amanda homeschools her children and starts craft projects she’ll never finish.

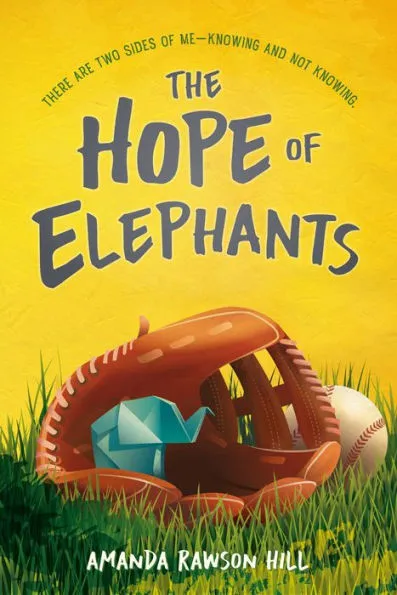

About The Hope of Elephants

An inspiring coming-of-age novel in verse about weathering the uncertainty that comes with family illness perfect for fans of Starfish and Red, White, and Whole.

Cass and her parents haven’t let her dad’s cancer stop them from having a good life—full of love and poems and one annual World Series game. Now that Dad’s cancer is back, Cass overhears the doctor say that she has a 50% chance of inheriting her dad’s genetic mutation, Li-Fraumeni syndrome. There’s a genetic test Cass can take that will tell her for sure. There’s still so much she wants to do—play baseball, study at the zoo, travel the world with her best friend, Jayla. Would it be better not to know?

When it turns out Dad’s cancer is worse this time, Cass is determined to keep up their World Series tradition while navigating all the change and uncertainty that lies ahead.

Poignant and powerful, Cass’s story brings the pains and anxiety linked with illness to the surface, and reminds us that sometimes hope is worth holding on to.

ISBN-13: 9781623542597

Publisher: Charlesbridge

Publication date: 09/06/2022

Age Range: 10 – 12 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

K is in Trouble | Review

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT