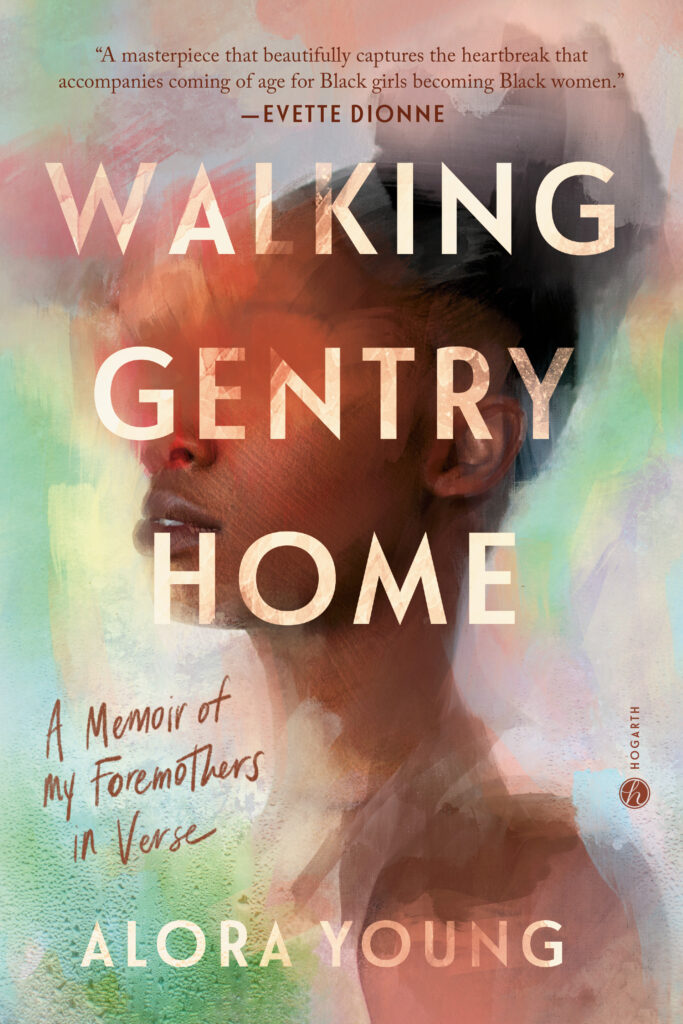

Never Forget the Lyrics: How Poetry Helped Me Overcome My Learning Disability and Become an Author, a guest post by Alora Young

I have always been a daydreamer. My mom says I used to talk myself to sleep at night. My brain moved too fast for its own good, and I was always consumed by shiny stories and tales that regaled my young mind. I started talking at ten months old and never stopped.

When I began school I discovered a disconnect between my love of words and my fingers. My handwriting was often illegible. My left-handedness combined with my dyslexia caused me to write whole sentences backward. My kindergarten teacher had to hold my writing up to a mirror to read it. That was the way my brain worked. The words made more sense in reverse.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

My teacher never judged me for my inverse iterations. She accepted them, and told me I had a great mind, and a great imagination, and that the rest, grammar and the like, would come later. I had that teacher for two years, and in that time I blossomed into a prolific storyteller. It was hard to read them, but I never considered that a reason to stop. I was enamored with the stories my father read to me every night, and I was unafraid of any word.

Until we moved from New Jersey to Tennessee when I was seven. The day we arrived at our rental house in Nashville, I wrote my first poem, “Stars of Sorrow See You Tomorrow.” Though I had already discovered poetry and loved to make my own rhymes, in Tennessee, all the things that hadn’t mattered in New Jersey were suddenly of world-ending importance to my teachers. Grammar. Spelling. Punctuation. It gave me a headache just thinking about all the rules and regulations on what had once been my escape. My teacher could tell I was bright, but she couldn’t see past the state of my writing. She told my mother I would never master English.

While I see the irony in this now, back then I was hurt at suddenly being perceived as subpar when I knew I wasn’t. From failing grades to exclusion from the honors courses, traditional elementary education tried everything to grind a love of writing and learning out of me.

I drudged through second and third grade, continuing to write poetry if only to have a place where the rules didn’t matter. Where I could rhyme and meld metaphors and spin similes and nobody could tell me I was wrong. My poetry was the avenue to a world of words outside of the confines Tennessee public schools wanted me to keep me in. My abstract mind was always strong and it stayed that way because of poetry. I continued to be a dreamer and to love words despite the best efforts of grammar and syntax.

Poetry saved me from the age-old story of being a learning disabled student who hates school and writing. I ate poetry for breakfast, lunch and dinner. For people like me reading can be deeply frustrating, but poetry, especially read aloud as my father used to, creates a phonics approach that emphasizes the use of rhythm and rhyme to keep my mind from getting bored. Spoken word poetry is just speech that can be crafted with the intent of maximum information retention using the mechanisms of language, literary and auditory devices to assist the brain, especially the neurodivergent brain in the process of learning. Voice, diction, imagery, figures of speech, symbolism, allegory, syntax, sound, rhythm, meter, and structure are all tools in the arsenal of spoken word education. Poetry widened my vocabulary and emphasized the joy and flexibility in language.

I became obsessed with the library. My love for poetry grew into a love of fiction, and I was reading far beyond the reading level I was supposed to be. I read Percy Jackson, A Light in the Attic, and the Wizard of Oz.

Art is a language spoken by all people, and poetry is a tool of communication underutilized in education. For students maintaining focus on a written document or lecture may be difficult, but performance is engrossing. For dyslexic students like me audible learning is vital.

Poetry was the perfect method for me to express my neurodivergent way of thought to people who would otherwise never understand it. It gave me a love for learning, confidence, and a way to express my feelings on hard topics like climate change and school shootings. It allowed me to weave facts with rhythm and color. Now it has given me a platform to tell my family’s story and an avenue to make all the change I want to in the world with my debut, Walking Gentry Home: A Memoir of My Foremothers in Verse.

I wouldn’t be where I am today without poetry, and there are thousands of neurodivergent students who could no doubt benefit from exposure to it like I did. Poetry has power. Poetry conveys power.

Traditional educational methods taught me that my mind didn’t work like everyone else’s. But poetry helped me realize that was a beautiful thing.

Meet the author

Alora Young is a college student, an actor, and the Youth Poet Laureate of the Southern United States. Her poetry has appeared in The New York Times and The Washington Post, and she has performed her poetry on CNN, CBS, and the TEDx stage. Originally from Tennessee, Young currently attends Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania. Her memoir in verse Walking Gentry Home, comes out August 2nd.

About Walking Gentry Home: A Memoir of My Foremothers in Verse

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

An “extraordinary” (Laurie Halse Anderson) young poet traces the lives of her foremothers in West Tennessee, from those enslaved centuries ago to her grandmother, her mother, and finally herself, in this stunning debut celebrating Black girlhood and womanhood throughout American history.

“A masterpiece that beautifully captures the heartbreak that accompanies coming of age for Black girls becoming Black women.”—Evette Dionne, author of Lifting as We Climb, longlisted for the National Book Award

Walking Gentry Home tells the story of Alora Young’s ancestors, from the unnamed women forgotten by the historical record but brought to life through Young’s imagination; to Amy, the first of Young’s foremothers to arrive in Tennessee, buried in an unmarked grave, unlike the white man who enslaved her and fathered her child; through Young’s great-grandmother Gentry, unhappily married at fourteen; to her own mother, the teenage beauty queen rejected by her white neighbors; down to Young in the present day as she leaves childhood behind and becomes a young woman.

The lives of these girls and women come together to form a unique American epic in verse, one that speaks of generational curses, coming of age, homes and small towns, fleeting loves and lasting consequences, and the brutal and ever-present legacy of slavery in our nation’s psyche. Each poem is a story in verse, and together they form a heart-wrenching and inspiring family saga of girls and women connected through blood and history.

Informed by archival research, the last will and testament of an enslaver, formal interviews, family lore, and even a DNA test, Walking Gentry Home gives voice to those too often muted in America: Black girls and women.

ISBN-13: 9780593498002

Publisher: Random House Publishing Group

Publication date: 08/02/2022

Age Range: 13 – 17 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

Review of the Day: My Antarctica by G. Neri, ill. Corban Wilkin

Exclusive: Giant Magical Otters Invade New Hex Vet Graphic Novel | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT