All the Ways to Be Strong and Brave, a guest post by Laurie Morrison

When I was in seventh grade, my class went on an outdoor education trip. We stayed in cabins and did lots of group bonding activities, and the centerpiece of the trip—the thing everyone else seemed most excited about—was a high ropes course.

I was not excited about the high ropes course.

It had wobbly bridges, towering ladders, and a zipline, all of which were—not surprisingly—very, very high above the ground. We had to take turns strapping on harnesses, clipping on ropes, and then traversing the whole thing as our classmates cheered us on from below. I was terrified that I wouldn’t make it across.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I did make it, but only after I fell off a tightrope bridge because my legs were trembling so hard that the wire wouldn’t stop shaking. I dangled there, attached to my rope with tears sliding down my cheeks, until I finally mustered the nerve to pull myself back up. A classmate whose turn was after mine had done the first parts of the course quickly, and he had to wait there, on a platform at one end of the bridge, until I got it together and got out of the way. Once I was back on solid ground, I cheered for the rest of the group like I was supposed to, but part of me hoped someone else would fall or cry like I had. I didn’t want to be the only “wimp.”

This wasn’t the first or last time I felt ashamed that I wasn’t “brave enough.” I’d loved soccer as a kid and played on a travel team for years, but when I started high school, sports got more intense, and I got worse instead of better. The more aggressive the other players were, the more tentative I became. I sat on the bench during big games, hoping the coach wouldn’t put me in and wishing I could be more like my toughest teammates, who threw their bodies at the ball with no fear of messing up or getting hurt.

Junior year of high school, my friends all seemed 100% excited about learning to drive, and I was at least 80% scared. When we were seniors, we went on another outdoor education trip, and I was the only person in my cabin who wasn’t on board with a prank that involved running outside in the middle of the night and making barnyard animal noises to wake the teacher chaperones. I thought we’d get in trouble, and I said so, but I was wrong. The teachers thought the prank was funny. I lay awake in my sleeping bag after it was over, berating myself for being so nervous about everything. Why I couldn’t be braver, more confident, more fun?

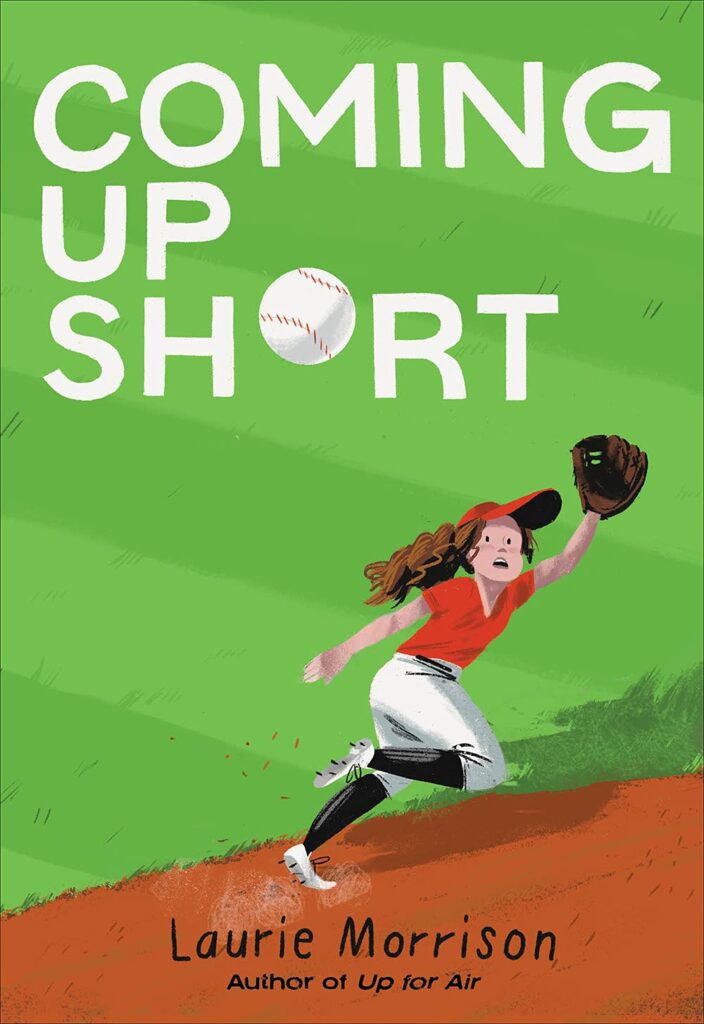

My new middle grade novel, Coming Up Short, stars a thirteen-year-old girl named Bea, who prides herself on her strength and courage. Bea loves softball more than anything else in the world, but after her dad makes a big mistake that costs him his job and reputation, she can’t think straight on or off the field. She makes error after error in the championship game and then sets off to visit her aunt in a place called Gray Island, where she gets a spot at a softball camp and is determined to fix her throw to first base.

It was invigorating to channel Bea. She’s the kind of girl I used to wish I could be (and sometimes still do). She always wants the ball when the game is on the line. She would have rocked that high ropes course.

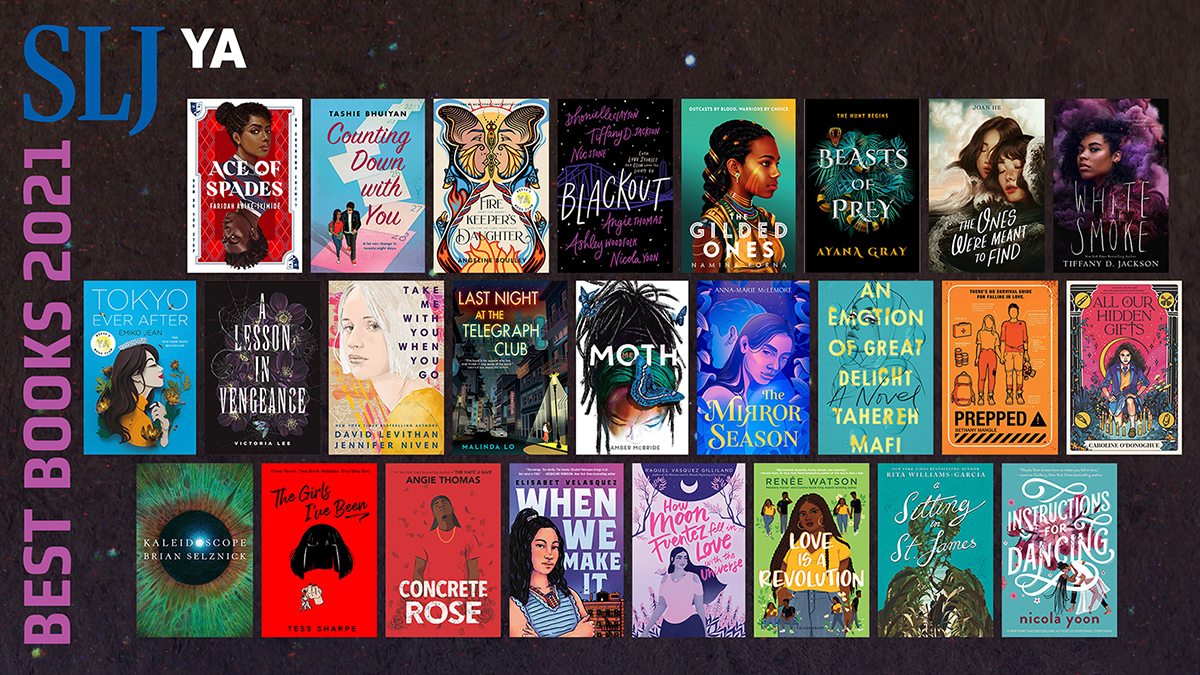

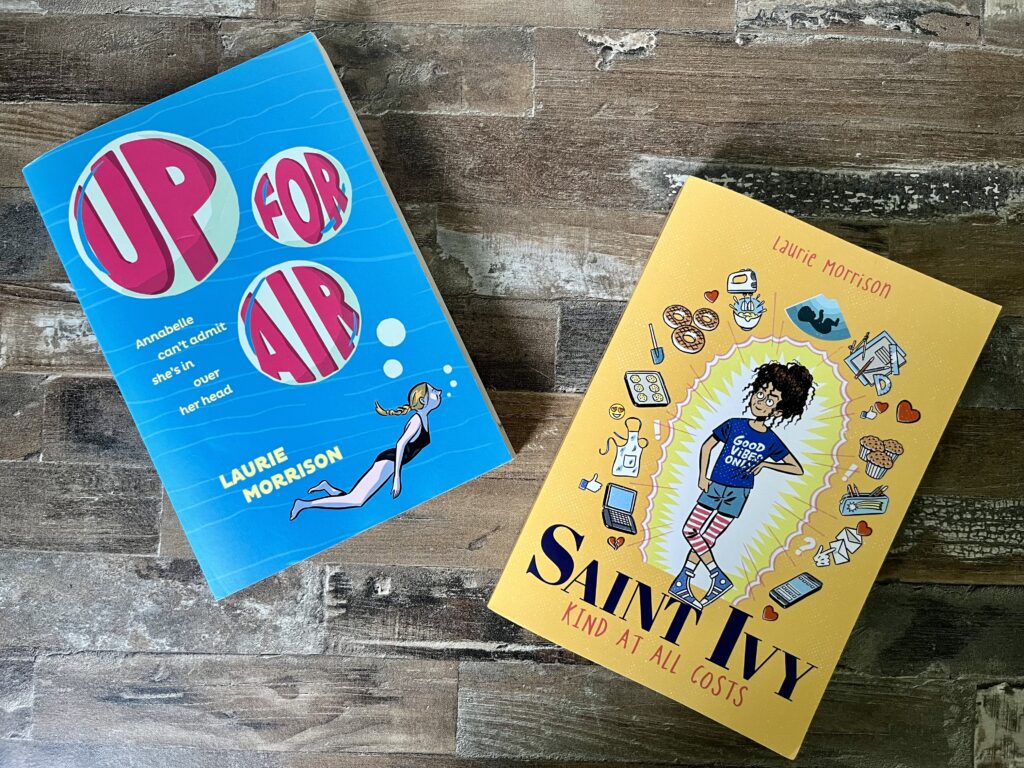

As I wrote, I also had this sense that Bea was the kind of feisty girl character whose story is seen as having more widespread appeal than my other novels. My last two books, Up for Air and Saint Ivy, star female main characters who are more introspective and less overtly confident than Bea is. And I’m often told they’re great stories for girls.

When people talk about “strong girls” or “fierce females” in middle grade novels, they’re usually talking about a certain kind of strength. And the books with bold, feisty female characters can feel easiest to recommend for whole class reads and book groups. People seem to believe, at least subconsciously, that quieter, more cautious girl characters might not be as widely relatable or inspiring. But the truth is that there are so many ways for everyone, regardless of gender, to be strong and brave.

I was so enamored with Bea’s feistiness that it took me a few drafts to figure out her emotional arc, but eventually, I realized that she needed to rethink her definitions of strength and courage, and I did, too. Bea has to recognize that being strong and brave can mean confronting hard, complicated feelings, even if they shake you to your core and leave you (metaphorically) dangling from a climbing rope crying while other people wait for you to get it together. She has to learn that there is strength in vulnerability, and that it’s brave to admit when you aren’t okay.

I didn’t feel strong or brave on that seventh-grade outdoor education trip, but I see now that I was. I was brave to get back up on that wobbly wire and make it to the zipline, which I actually enjoyed. And I would have been brave in a different but equally valid way if I hadn’t gotten back up on that wire. If I’d said, “No. I don’t want to do this. Please lower me down.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I was brave to stick with soccer after I’d lost my confidence, and I was even braver to quit before my senior season so I could try out for the fall play instead. I was brave to learn to drive despite being nervous, and my cautiousness behind the wheel was an asset, not a weakness. I was brave to speak up and say I wasn’t comfortable with a prank that everyone else thought would be fun. But I didn’t appreciate my own kinds of strength and courage in any of those situations because they didn’t match the definitions I’d internalized.

I still hope, of course, that Coming Up Short will have widespread appeal. I hope readers will love Bea when she’s at her feistiest and her most vulnerable. But I also hope that we can make a concerted effort to celebrate the strength and courage of all kinds of characters—and all kinds of people. If we’re going to talk about “strong girls” in middle grade fiction, let’s broaden our definition of what strong means. Let’s try to make it clear to kids that there are many wonderful ways of being strong.

Meet the author

Laurie Morrison taught middle school for ten years and now writes middle grade novels. Laurie is the coauthor of Every Shiny Thing and the author of Up for Air, Saint Ivy, and Coming Up Short. Her books have been chosen as Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selections and finalists for state award lists, and Up for Air received two starred reviews and was a Publishers Weekly Best Summer Read. Laurie holds an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts, and she lives with her family in Philadelphia. You can find her on Twitter and Instagram @LaurieLMorrison or visit her website at lauriemorrisonwrites.com.

About Coming Up Short

A heartfelt novel about a softball-loving girl coming to terms with her parents’ humanity after a scandal sends shock waves through her town

Bea’s parents think she can accomplish absolutely anything—and she’s determined to prove them right. But at the end of seventh grade, on the same day she makes a gutsy play to send her softball team to the league championships and Xander, the boy she likes, makes it clear that he likes her too, a scandal shakes up her world. Bea’s dad made a big mistake, taking money that belonged to a client. He’s now suspended from practicing law, and another lawyer spread the news online. To make matters worse, that other lawyer is Xander’s dad.

Bea doesn’t want to be angry with her dad, especially since he feels terrible and is trying to make things right. But she can’t face the looks of pity from all her friends, and then she starts missing throws in softball because she’s stuck in her own head. The thing she was best at seems to be slipping out of her fingers along with her formerly happy family. She’s not sure what’s going to be harder—learning to throw again, or forgiving her dad. How can she be the best version of herself when everything she loves is falling apart?

ISBN-13: 9781419755583

Publisher: Amulet Books

Publication date: 06/21/2022

Age Range: 10 – 14 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

Passover Postings! Chris Baron, Joshua S. Levy, and Naomi Milliner Discuss On All Other Nights

Team Unihorn and Woolly | This Week’s Comics

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT