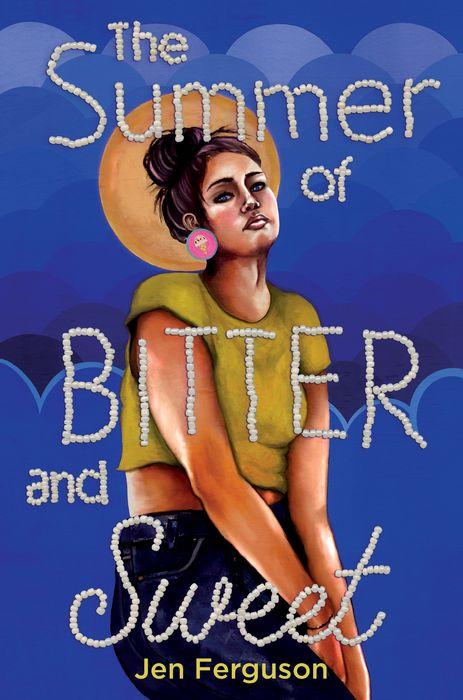

Let’s Talk About Coming Out (in Life and Fiction), a guest post by Jen Ferguson

I’m out on twitter and have been for a long-ish while. At least, I’m out as a kick-ass demisexual. I don’t often talk about the fact that my attraction, when it shows up, isn’t confined by any specific gender. That being said, as much as some of us think so, the internet isn’t everything. I am not out—in any way—in most of my other life spaces. I’ve only started being okay calling myself queer in academic spaces, and only because I’ve been anticipating my debut YA release. On May 10, 2022, when The Summer of Bitter and Sweet publishes, that will be, my official public “coming out.”

Oof. That’s heavy.

Exciting in some ways. Absolutely, completely bloody terrifying in others.

We’ve been taught by YA books (I’m looking at you, Simon and the Homosapien Agenda) and other media (the accidental outing of Patrick to his parents on Schitt’s Creek) that if you don’t come out and come out fast enough and come out widely enough, a come out will be forced upon you. It’s so pervasive, it’s become a literary trope.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Most tropes, in themselves, are not good or bad. They are… neutral. But all tropes can be used to serve harmful purposes.

That trope—Forced Out of the Closet—underpins how most straight readers understand the queer experience. And that has wide-reaching consequences. It means that queer stories, in the hands of straight editors, straight librarians and straight readers who expect that a queer storyline should have a coming out, and that coming out should be dramatic and/or traumatic, because it must be dramatic and/or traumatic to announce one’s deviation from the so-called default, these queer stories insidiously replicate that experience, that is, the forced come out, as true, as required. Often, this trope finds the queer character happy after their forced outing, like see, it was worth it. This narrative of a happy-ending forced come out centers the cis-het experience and reaffirms that power remains in the hands of the straight characters, and therefore in the hands of straight cis readers.

Can you see how harmful this is?

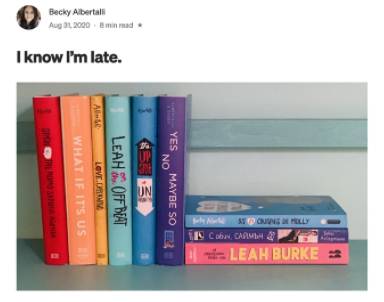

And the harm spreads. Outward. We now expect authors of queer stories to offer us their queer identities as proof they are allowed to write about queer experiences. And if they don’t, we’ll force it. Like the folks on twitter dot com did to Becky Albertalli.

I’m not saying these real life experiences happen as a direct correlation to media instances of the the Forced Out of the Closet trope. But I am saying that replicating this narrative in our fictions, replicates its power. And power gets used by whomever can harness it. Storytellers, yes, we have power. So do librarians. We have more power than we think we do. We also have a responsibility to use that power well.

Forced come outs are also a real experience many queer kids and teens go through. Adiba Jaigirdar’s The Henna Wars uses a forced come out as part of a larger plot, and it’s complicated further by having a white classmate out our Bengali, Muslim lesbian protagonist. In Kacen Callender’s Felix Ever After, Felix being anonymously dead-named acts as a catalyst for the novel’s plot. Because forced come outs happen, we should absolutely write about them.

Me, I’m not waiting for the world to force me to come out on its terms. I’m doing it pre-emptively. And I’m doing with the publication of my debut YA novel, which is just big. Celebratory. Dare I say, fun?! That I can do this, safely, says something about my privilege. I don’t want that not to be clearly acknowledged.

Queer identity, like all other identities, needs to be represented in many, many different queer stories. We need all kinds of come outs and we need queer stories where there are no come outs. Queer readers need these many stories, but so do non-queer readers. We need variety in representing the queer experience because that’s real life. Some of us are forced out, some of us come out with a big party, and some of us don’t come out publicly at all.

It’s not one-size-fits-all and neither should our books, or our bookshelves, be. Among the #22Debuts, you’ll find lots and lots of different queer stories, for kids, teens, and adults—and I hope that this will continue to happen year after year. Because queer readers and non-queer readers deserve a plethora of queer representations. There ought to be many tropes in the media, many ways for queer readers to imagine their experience, and many ways for straight readers to imagine the lives of their queer classmates, neighbors and friends.

I didn’t set out in The Summer of Bitter and Sweet to write a queer book that purposefully didn’t have a public come out as part of the plot, or Lou, my demisexual main character’s arc. It sort of just happened. Now, I’m thinking it’s because it parallels my own experience. Oof, double oof. I only just realized that!

In the novel, eighteen-year-old Métis teen Lou comes out to exactly two people. Her Trini-Jamaican-Canadian friend King who is helping her figure out this attraction business. And to her deeply problematic, white ex-boyfriend Wyatt. I’d like to think briefly about that second come out scene with you all.

Lou tells Wyatt she’s demisexual and she’s not doing it because she’s telling everyone in her community she’s queer. After all, since her family’s having a community-wide BBQ it would be a great day to do that, in a public, celebratory way. But she doesn’t. Instead, she tells Wyatt she’s demisexual to reclaim her power. To take back the things he took from her during their short, unpleasant relationship.

Maybe my come out too is about reclaiming power.

At the very least, it’s about not letting others force me into being out. It’s about choosing this for myself.

Hi, I’m Jen and I’m queer. That’s my preferred word choice. And I think it’s the one I use because queer is nebulous. In calling myself queer, even in public spaces, I still get to hold onto privacy. Depending on my audience, I can get more specific.

(Image Description: Jen wandering through an immersive art experience in Salt Lake City, Utah, May 2019.)

So, let’s raise a frosty glass of Mexican Coke with a slice of lime to many queer stories. Here’s to many come outs. Here’s to not having to come out at all. Here’s to coming out for your own reasons, on your own timeline. Here’s to our bookshelves and our libraries reflecting all of this—and much more!

Meet the author

(Photo Credit: Mel Shae)

Jen Ferguson is Métis/Michif and white, an activist, an intersectional feminist, an auntie, and an accomplice armed with a PhD in English and Creative Writing. Her favorite ice cream is mint chocolate chip. Visit her online at www.jenfergusonwrites.com.

Links:

Websites: www.jenfergusonwrites.com; www.22debuts.com/jen-ferguson.html

Twitter: @JennyLeeSD

Instagram: @JDotFerg

HarperCollins: www.harpercollins.com/products/the-summer-of-bitter-and-sweet-jen-ferguson?variant=39664883007522

About The Summer of Bitter and Sweet

In this complex and emotionally resonant novel about a Métis girl living on the Canadian prairies, debut author Jen Ferguson serves up a powerful story about rage, secrets, and all the spectrums that make up a person—and the sweetness that can still live alongside the bitterest truth.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Lou has enough confusion in front of her this summer. She’ll be working in her family’s ice-cream shack with her newly ex-boyfriend—whose kisses never made her feel desire, only discomfort—and her former best friend, King, who is back in their Canadian prairie town after disappearing three years ago without a word.

But when she gets a letter from her biological father—a man she hoped would stay behind bars for the rest of his life—Lou immediately knows that she cannot meet him, no matter how much he insists.

While King’s friendship makes Lou feel safer and warmer than she would have thought possible, when her family’s business comes under threat, she soon realizes that she can’t ignore her father forever.

The Heartdrum imprint centers a wide range of intertribal voices, visions, and stories while welcoming all young readers, with an emphasis on the present and future of Indian Country and on the strength of young Native heroes. In partnership with We Need Diverse Books.

ISBN-13: 9780063086166

Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers

Publication date: 05/10/2022

Age Range: 13 – 17 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

Passover Postings! Chris Baron, Joshua S. Levy, and Naomi Milliner Discuss On All Other Nights

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT