Teach Our Children Well, a guest post by Michelle Coles

“I believe the children are our future. Teach them well and let them lead the way.” Whitney Houston, The Greatest Love of All (1986)

The Children are Our Future

I remember the first time I heard Whitney Houston’s epic rendition of The Greatest Love of All. I was five years old, prancing through the halls of my elementary school with my ragtag group of girlfriends. We belted out the lyrics to each other, feeling both inspired and empowered upon hearing such a beautiful song about an adult’s faith in us.

Now that I’m in my 40s and the proud mother of four precocious boys, I find myself looking at my children with the same sense of hope for a better tomorrow. Can the next generation finally heal the longstanding fractures in our society and solve problems that have eluded grownups for ages? One dilemma that outshines them all is the paradox of growing up Black in America, a nation that claims to be “the land of the free,” but has yet to redress its past steeped in the trafficking, enslavement, and subjugation of millions of people of African descent.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

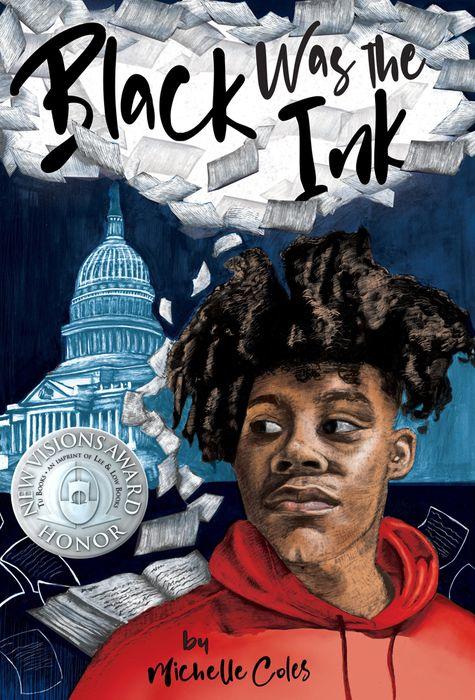

Black Was the Ink

I wrote my debut young adult historical fiction novel, Black Was the Ink, to help young people understand why America’s racial divide is so pronounced and seemingly intractable. While most Americans acknowledge the horrors of the slave trade, there is a general lack of awareness of the terror African Americans experienced in the century that followed, the Jim Crow Era, and even less awareness about the period that separated slavery and Jim Crow — the Reconstruction Era. In this brief period, which lasted from about 1865 to 1876, Black people gained access to the hallmarks of American democracy — political participation and economic prosperity — for the very first time. Suddenly, after centuries of enslavement, the opportunity to get an education, vote, live with one’s family, serve on juries, hold public office, earn money from one’s labor, build savings, start a business, and purchase land was within reach! The possibilities were endless . . . for the time being.

Told through the eyes of an African American teenager named Malcolm, who miraculously travels to the Reconstruction Era from the year 2015, Black Was the Ink reveals the best and the worst of the Reconstruction Era, while also exploring how Malcolm deals with present-day issues like police brutality, mass incarceration, and unjust eminent domain claims on his family’s farmland.

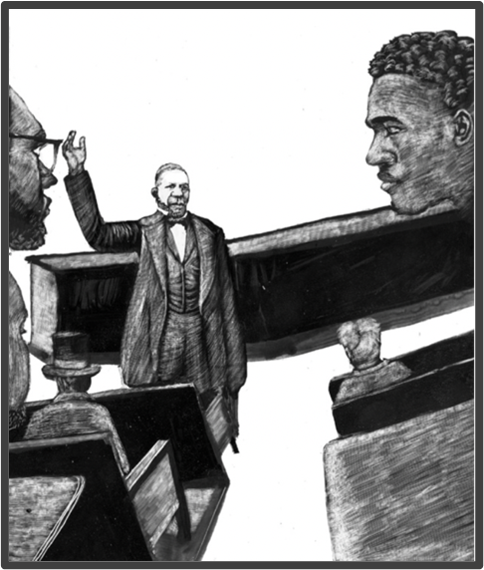

Malcolm sees the best of Reconstruction in the swearing in of the first Black member of Congress, Senator Hiram Revels, the founding of Historically Black Colleges and Universities, the passage of numerous bills designed to protect the civil rights of America’s newest citizens, and the creation of the U.S. Department of Justice in large part to enforce those laws.

Malcolm witnesses both White and Black people working together in the Reconstruction Era to make America a more just and inclusive society. He is awestruck when he meets Robert Smalls, a formerly enslaved person, Civil War hero, and congressman from South Carolina who introduced the first state-funded public education system into a southern state’s constitution.

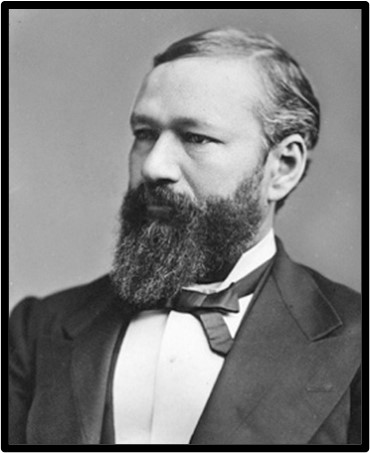

Malcolm is roped into helping Senator Charles Sumner, a White senator from Massachusetts, and John Mercer Langston, the first Black person to hold elected office in the United States, draft the extraordinary Civil Rights Act of 1875. This bill prohibited racial discrimination in public places until the Supreme Court struck it down a few years later. Nevertheless, the Civil Rights Act of 1875 served as the blueprint for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which Congress passed almost 100 years later to finally bring an end to the dreadful Jim Crow Era.

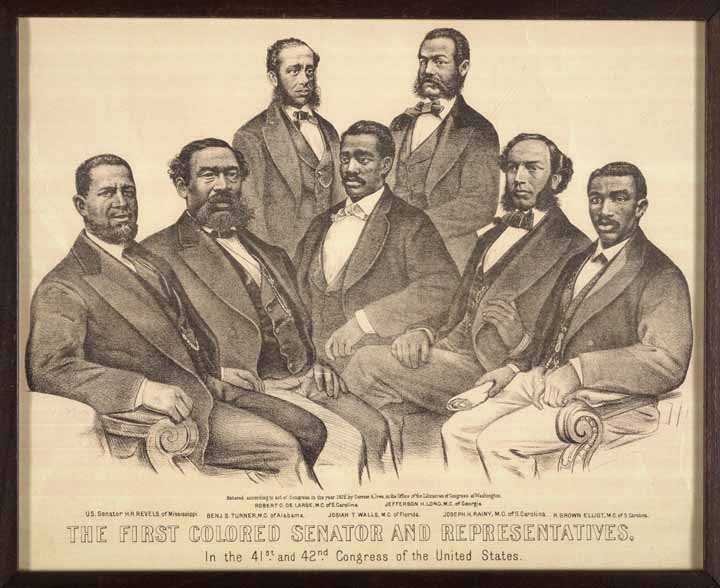

During the Reconstruction Era, Black people voted and held political office in numbers that would not be seen again for over 100 years. Fifteen Black men served in Congress in the 1870s, including two as U.S. Senators. In Black Was the Ink, Malcolm has the opportunity to work alongside many of them and witness their brilliance first hand.

Just to name a few, Blanche Bruce was the first Black person to serve a full term in the United States Senate, representing Mississippi from 1875-1881. Not another Black senator represented a southern state, where the majority of Black people reside, until 2013!

P.B.S. Pinchback had a brief tenure as the Governor of Louisiana in 1872, making him the first Black governor as well as the only until Douglas Wilder was elected Governor of Virginia in 1990, nearly 120 years later.

Malcolm also sees the worst of Reconstruction in the campaign of domestic terrorism that white supremacists waged against Black people across the South leading to countless forgotten massacres. Pivotal moments in the book occur when Malcolm witnesses the aftermath of the Mechanics’ Institute and Colfax Massacres, which took place in Louisiana, and the Hamburg Massacre in South Carolina. Through his travels to the past, Malcolm gains a deeper understanding of Supreme Court decisions that reversed the progress of the Reconstruction Era as well as an appreciation for his family’s ties to their farmland.

Teach Them Well and Let Them Lead the Way

During the Jim Crow Era, the Lost Cause narrative was used to elevate the Confederacy and obscure the many accomplishments of the interracial governments from the Reconstruction Era. The terrifying truth is that, 150 years later, this narrative continues to shape much of our country’s cultural norms. Everything from the heroes memorialized in statues, to the streets we drive on, to the names of schools and the history taught within, continues to reflect that skewed version of events.

Some people may claim that Black Was the Ink is an attempt to rewrite history. No. It is an attempt to write in the perspectives of people who were deliberately left out or mischaracterized for the sake of propaganda.

As state legislatures around the country pass laws restricting the perspectives that our children are exposed to in the classroom, it becomes all the more imperative that parents, teachers, librarians and students seek out the stories of people whose voices have been silenced for far too long.

Ultimately, it is up to us to determine who we are as a nation. Our children are our future. We teach them well when we help them confront the realities of our past, warts and all. Only then, will they be prepared to lead us towards a brighter and more inclusive tomorrow.

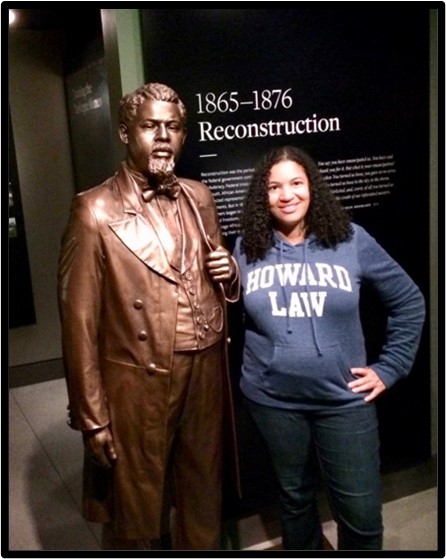

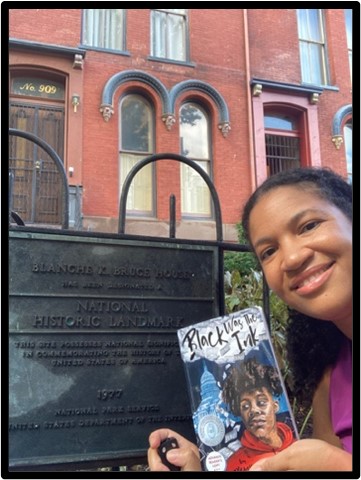

Meet the author

Michelle Coles is a debut novelist, experienced civil rights attorney, and mother of four. As a 9th generation Louisianan, she is highly attuned to the struggles that African Americans have faced in overcoming the legacy of slavery and the periods of government-sanctioned discrimination that followed. Her goal in writing is to empower young people by educating them about history and giving them the tools to shape their own destiny. Her website is: www.michellecoles.com. Follow her on social media:

Instagram @michellecolesauthor | Twitter @mjcoles2015 | Facebook @michellejcolesauthor

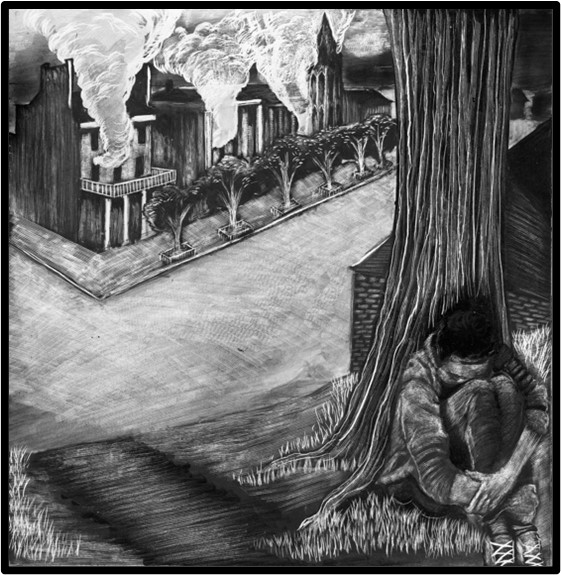

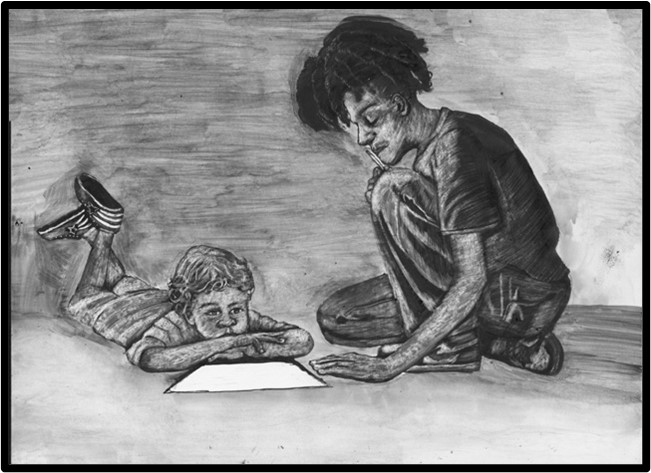

Black Was the Ink was published by Tu Books, an imprint of Lee and Low Books, on November 2, 2021, and illustrated by Justin Johnson, a talented artist and D.C. public school art teacher. http://justinjohnson.work/

It is a recipient of the New Visions Award Honor and received a starred review from Booklist, the book review journal of the American Library Association. As an additional resource, check out Black Was the Ink’s Teacher’s Guide, which can help you tackle difficult topics: https://blog.leeandlow.com/2021/10/07/teaching-about-united-states-reconstruction-with-black-was-the-ink/.

About Black Was the Ink

Through the help of a ghostly ancestor, sixteen-year-old Malcolm is sent on a journey through Reconstruction-era America to find his place in modern-day Black progress.

Forgotten heroes still leave their mark.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Malcolm Williams hasn’t been okay for a while. He’s angry and despondent and feels like nothing good ever happens for teens like him in D.C. All he wants is to be left alone in his room for the summer to draw or play video games—but no such luck. With growing violence in his neighborhood, his mother ships him off to his father’s family farm in Mississippi, and Malcolm is anything but pleased.

A few days after his arrival, his great-aunt tells him that the State is acquiring the farm to widen a highway. It’s not news Malcolm is concerned about, but someone plans to make it his concern. One minute Malcolm is drawing in the farmhouse attic, and the next he’s looking through the eyes of his ancestor Cedric Johnson in 1866.

As Cedric, Malcolm meets the real-life Black statesmen who fought for change during the Reconstruction era: Hiram Revels, Robert Smalls, and other leaders who made American history. But even after witnessing their bravery, Malcolm’s faith in his own future remains shaky, particularly since he knows that the gains these statesmen made were almost immediately stripped away. If those great men couldn’t completely succeed, why should he try?

Malcolm must decide which path to take. Can Cedric’s experiences help him construct a better future? Or will he resign himself to resentments and defeat?

Perfect for fans of Jason Reynolds and Nic Stone, and featuring illustrations by upcoming artist, Justin Johnson, Black Was the Ink is a powerful coming-of-age story and an eye-opening exploration of an era that defined modern America.

ISBN-13: 9781643794310

Publisher: Lee & Low Books

Publication date: 11/02/2021

Age Range: 13 – 18 Years

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Watch the 2025 Youth Media Awards LIVE!

Confidence, Language, and Awesome Abuelas: Julio Anta and Gabi Mendez Discuss the Upcoming Speak Up, Santiago!

Mini Marvels: Hulk Smash | Review

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

Our 2025 Preview Episode!

ADVERTISEMENT