Shame on You: Desi Shame Culture and its Impact on Muslim Kids, a guest post by Farah Naz Rishi

A long time ago, my local masjid hosted a Ramadan dinner, as it always did in the holy month of fasting for Muslims. Usually, these dinners meant praying together as a community, and breaking our fast together on a potluck style meal that involved samosas, curries, and the ubiquitous, vague semblance of a pasta dish.

However, I had other plans.

After that one particular dinner, under cloak of darkness, I slipped out of the masjid and walked to the nearby Sunday school, a small cottage that had been converted into a schoolhouse. That night, it was empty of students—save for the boy I was secretly “dating” at the time, waiting for me.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I cherished these Ramadan dinners because it was the only time he and I could see each other in person. Being South Asian Muslims in a conservative community meant hiding our illicit, budding romance, even if everyone already knew about it. It didn’t matter that we were a couple of awkward teens who only snuck out to talk, face-to-face, uninterrupted (we usually only talked through text messages). As far as anyone knew, we were lovers in the dark, the epitome of sin. All our lives, we’d been taught that the performance of being a “good Muslim,” of maintaining one’s public image for the sake of family and community honor, was to be valued above all else. A lesson that clearly didn’t take.

Which is why, when we were caught that night, one uncle in our community loudly proclaimed that if we were caught alone again, he would break our legs. My parents didn’t speak to me for days.

I was fourteen years old.

In IT ALL COMES BACK TO YOU, protagonists Kiran and Deen, who dated in the past, reveal that they had made pact to hide their relationship from their family. Kiran notes that she kept her relationship with Deen a secret because she didn’t want to “add stress” to her family: “Dating in the casual sense,” she says, “is still frowned upon Muslim communities, and it’s not something you can openly talk about unless you’ve practically made a formal Jane Austen-style declaration that you’re in pursuit of a life partner.” In the Muslim community I grew up in, this was precisely the case; dating carried a stigma, and that to date meant that I was a sinner, that I must have a weak faith. Regardless of my own religious beliefs—individual beliefs that I was still developing myself, on top of everything else—it felt that my community demanded I follow their brain trust iron-clad rules. That in some way, developing my own personal beliefs was wrong, too.

I wasn’t alone in this feeling. Although there are exceptions, many South Asian teens are expected to live up to their parents’ origin country’s cultural and religious standards, or at the very least, do so on the surface—all in the name of maintaining public image and family honor. And when one fails to do so, like in the case of Deen, one carries that shame and guilt for years to come, a weight that drowns you in a sea of expectation, and can lead to a self-destructive spiral.

The concept of honor reflects a family’s reputation and prestige within a community; and individual actions can raise of lower the entire family’s honor. Looking back on my own past experiences, it almost makes sense why some Muslim teens want to leave their community altogether: It gets exhausting seeing everything through the lens of shame and honor. Every act in life carries the extra consideration of, how would this affect my family and community? As if life isn’t already difficult as it is for a brown teenager.

Also exhausting? Being a second-generation immigrant teen balancing mainstream Western cultural norms and one’s family’s traditional values. It can often feel like an isolating experience, growing up too “westernized” to be accepted by the motherland, but too brown to be anything else. You are forever the Other. It makes sense, then, to find love with a fellow misfit trapped in the same limbo space. In this love, you can find an ally: someone who understands why you can’t go to sleepovers with friends from school, why you can’t go to school dances, and why sometimes it feels impossible to reconcile the need for emotional connection with your parent’s religious views.

But for those teens who aren’t lucky enough to find that ally, the sense of isolation can prevent them from seeking help when they need it most. In the case of Deen’s older brother, Faisal, the pressures of growing up in an influential family, of being anything less than perfect, became too much to handle. And instead of having an open, transparent conversation—one necessary for healing—Faisal’s parents tell him to hide his pain for the sake of the family’s honor. Of course, this eventually results in Faisal’s sense of failure reaching an unavoidable and dangerous fever pitch. For many, this is an experience far from fiction. As “shame culture” is most utilized as a method of control in Asian communities, Asian American young adults are the only racial group with suicide as their leading cause of death (source: https://theconversation.com/asian-american-young-adults-are-the-only-racial-group-with-suicide-as-their-leading-cause-of-death-so-why-is-no-one-talking-about-this-158030).

I wrote IT ALL COMES BACK TO YOU because I wanted my younger self to feel seen and understood. I wanted a wider audience to understand how difficult it was to grow up, for better or worse, in a tight-knit community that felt like it was always watching, and how the threat of shame can have very real, dangerous consequences on our mental health, and stain the perfectly innocent act of growing up.

My parents and I never spoke again of that night at the Sunday School. Despite their obvious disappointment with me, they carried on as if nothing happened. Instead of using it as a learning opportunity, a chance to connect and know more about their daughter’s personal life, they swept it under the rug. I suppose the public shaming we received was enough.

But there’s no room for growth if we’re not allowed to make mistakes. The irony is that using “shame culture” as a weapon to control often drives teens to hide under cloak of night, and internalize that hiding our shame is better than communicating it—the original problem that drove Kiran and Deen apart in the past. This is precisely why I wrote IT ALL COMES BACK TO YOU: to show South Asian Muslim teens who are finally able to break the silence—and that ultimately, the most important lesson any teen can learn is that despite those who pretend otherwise, we’re human, flaws and all.

And there’s no shame in that.

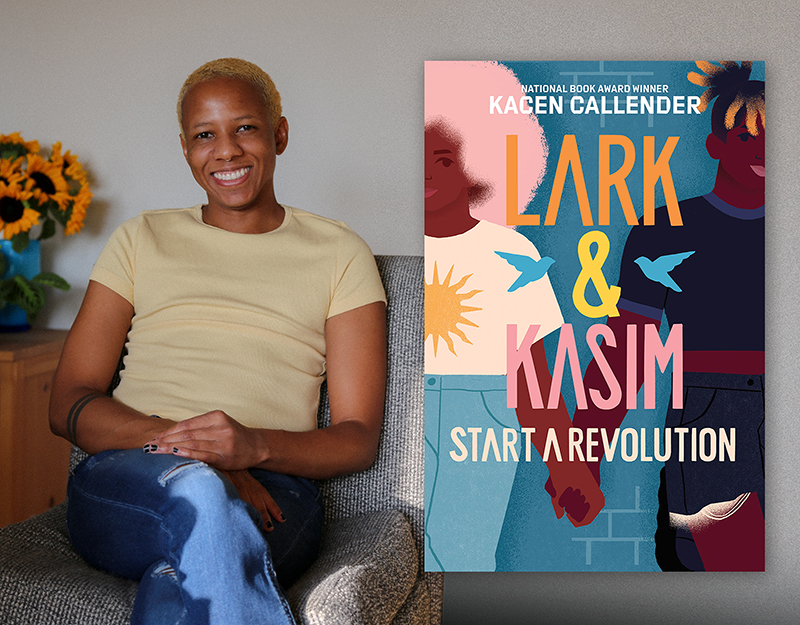

Meet the author

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Farah Naz Rishi is a Pakistani American Muslim writer and voice actor, but in another life, she’s worked stints as a lawyer, a video game journalist, and an editorial assistant. She received her BA in English from Bryn Mawr College, her JD from Lewis & Clark Law School, and her love of weaving stories from the Odyssey Writing Workshop. When she’s not writing, she’s probably hanging out with video game characters. She is the author of I Hope You Get This Message. You can find her at home in Philadelphia, or on Twitter and Instagram @farahnazrishi. Learn more at https://farahnazrishi.com.

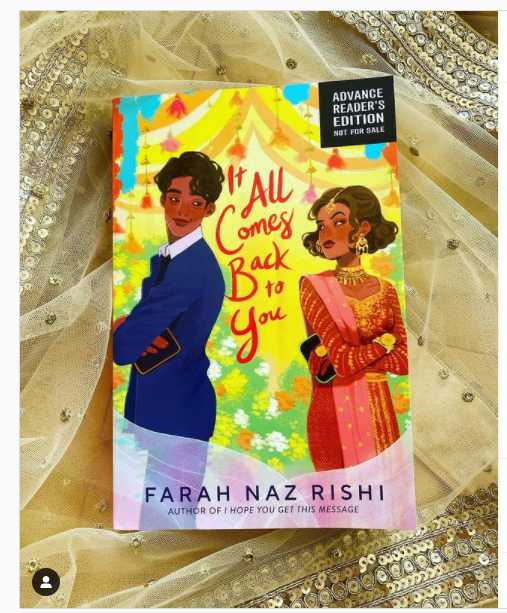

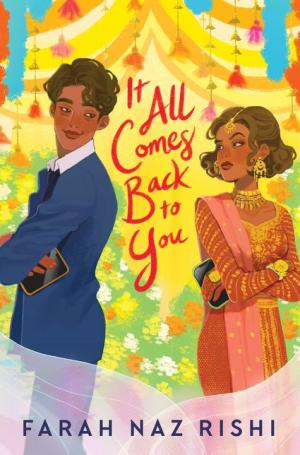

About It All Comes Back to You

Two exes must revisit their past after their siblings start dating in this rom-com perfect for fans of Sandhya Menon and Morgan Matson.

After Kiran Noorani’s mom died, Kiran vowed to keep her dad and sister, Amira, close—to keep her family together. But when Amira announces that she’s dating someone, Kiran’s world is turned upside down.

Deen Malik is thrilled that his brother, Faisal, has found a great girlfriend. Maybe a new love will give Faisal a new lease on life, and Deen can stop feeling guilty for the reason that Faisal needs a do-over in the first place.

When the families meet, Deen and Kiran find themselves face to face. Again. Three years ago—before Amira and Faisal met—Kiran and Deen dated in secret. Until Deen ghosted Kiran.

And now, after discovering hints of Faisal’s shady past, Kiran will stop at nothing to find answers. Deen just wants his brother to be happy—and he’ll do whatever it takes to keep Kiran from reaching the truth. Though the chemistry between Kiran and Deen is undeniable, can either of them take down their walls?

ISBN-13: 9780062741486

Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers

Publication date: 09/14/2021

Age Range: 13 – 17 Years

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Notes on November 2024

Free to Be You and Me: Curator Margi Hofer on This Once In a Lifetime Exhibit

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles/Naruto #1 | Review

Mock Newbery 2024: Last Minute Pleas

The Seven Bills That Will Safeguard the Future of School Librarianship

ADVERTISEMENT