How to Pronounce Quach, a guest post by Michelle Quach

Many years ago, while reading Sideways Stories from Wayside School, I stumbled upon this tidbit in Louis Sachar’s author bio:

“When Louis Sachar was going to school, his teachers always pronounced his name wrong. Now that he has become a popular author of children’s books teachers all over the country are pronouncing his name wrong.”

That made me chuckle. I was nine, and teachers had been pronouncing my name wrong for years, too.

My last name is Quach, which, like Sachar, has that elusive hard “ch” sound that has thrown off many, many Americans. I don’t blame them—“Quash” or “Quatch” both seem like perfectly reasonable guesses for a name that looks like Quach. But I didn’t see why I should have a name that sounded like “squash” or “crotch” when I could instead be a much more solid Quach. One that rhymed with nouns of substance, like “lock” and ”rock.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

In spite of the trouble, however, I’ve always liked my name. In one word, it uniquely encapsulates my family’s complicated history—a history that I’ve often found hard to explain.

Quach is an Americanized version of the Vietnamese Quách, which itself is derived from the Chinese surname 郭 (often romanized as Kwok or Guo). It’s common among people like my family, ethnic Chinese who lived in Vietnam for several generations before they immigrated to the U.S. as refugees. We might still be living in Hanoi now if it hadn’t been for the aftermath of the Vietnam War.

So whenever I’ve been asked what I “am,” the answer has been complicated. Growing up, I wasn’t exactly sure how to identify. It wasn’t quite as clean-cut as if, say, my mom were Chinese and my dad were Vietnamese. In reality, both sides of my family are technically Chinese: my ancestors originated in southern China, and the one language that almost all of us still speak is Cantonese. But my grandparents and parents were born in Vietnam—to say that they’re not really Vietnamese is like saying I’m not really American. Vietnamese has been as much part of our household as English.

Still, when I talk to Chinese people, I don’t quite feel Chinese enough, and when I talk to Vietnamese people, I don’t feel quite Vietnamese enough. This is true even when I talk to Chinese- and Vietnamese-Americans, because their histories—where their families came from and how they made their way to the U.S.—are often so different from mine.

It wasn’t until I learned the concept of diaspora that I finally began to feel seen. For the first time, I had the vocabulary to describe my muddled identity, and I learned that my family was less “Chinese” than “overseas Chinese.” Specifically, they were already overseas Chinese before they came to America, and that—with their code-switching between languages, fusion of cultural cuisines, and history of migration and displacement—has always been a distinct and valid way of being Chinese. It also, I realized, happens to be a valid way of being Vietnamese—and a valid way of being American, too.

When I started writing Not Here to Be Liked, I knew I wanted Eliza, the main character, to share my experiences as a child of Asian immigrants, but I wasn’t sure how to approach her background. I wondered if patterning it on my own would require too much explanation, and I briefly considered making her Chinese-American in a way that most readers would already understand. Ultimately, though, I wanted the book to be true to the diversity in the Asian American experience, so I gave her an identity as multifaceted as my own.

I feel incredibly fortunate that I now have the opportunity to write about characters like me, with families like mine. I’m proud to contribute in some small way to the complexity of Asian representation, and I hope that Eliza’s story will resonate with readers like my younger self.

Maybe, if I’m lucky, teachers all over the country will be saying my name, too—the right way.

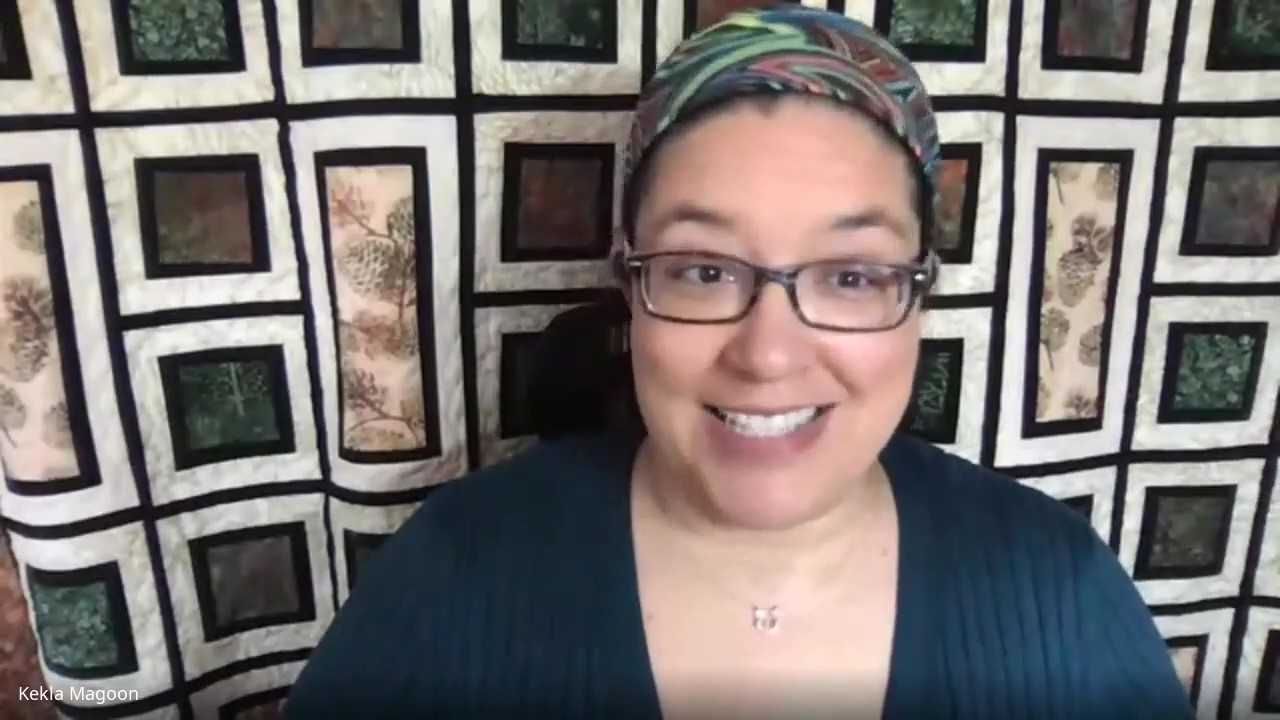

Meet the author

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Michelle Quach is a Chinese-Vietnamese-American who also spent a lot of time working for student newspapers–including The Crimson at Harvard College, where she earned a BA in history and literature. Currently a graphic designer at a brand strategy firm in Los Angeles, Not Here to be Liked is her first novel.

Buy Michelle’s book at one of her favorite indie bookstores, The Ripped Bodice.

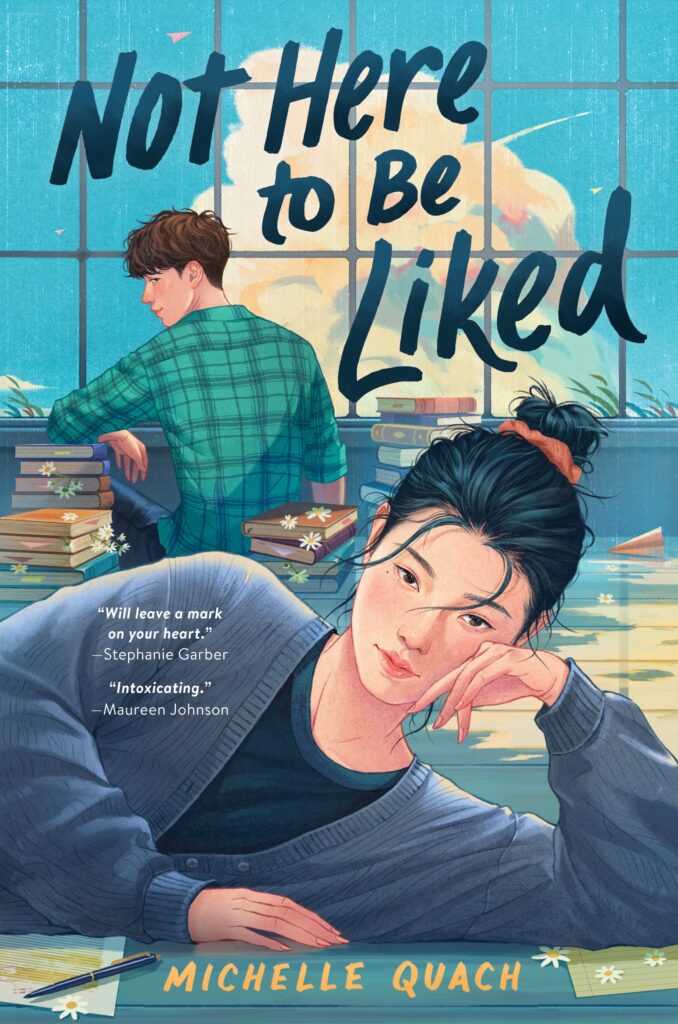

About Not Here to Be Liked

Emergency Contact meets Moxie in this cheeky and searing novel that unpacks just how complicated new love can get…when you fall for your enemy.

Eliza Quan is the perfect candidate for editor in chief of her school paper. That is, until ex-jock Len DiMartile decides on a whim to run against her. Suddenly her vast qualifications mean squat because inexperienced Len—who is tall, handsome, and male—just seems more like a leader.

When Eliza’s frustration spills out in a viral essay, she finds herself inspiring a feminist movement she never meant to start, caught between those who believe she’s a gender equality champion and others who think she’s simply crying misogyny.

Amid this growing tension, the school asks Eliza and Len to work side by side to demonstrate civility. But as they get to know one another, Eliza feels increasingly trapped by a horrifying realization—she just might be falling for the face of the patriarchy himself.

ISBN-13: 9780063038363

Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers

Publication date: 09/14/2021

Age Range: 13 – 17 Years

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

This Q&A is Going Exactly As Planned: A Talk with Tao Nyeu About Her Latest Book

More Geronimo Stilton Graphic Novels Coming from Papercutz | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT