We Need to Talk: An Interview with Wade Hudson, Cheryl Willis Hudson, and Brendan Kiely By Lisa Krok

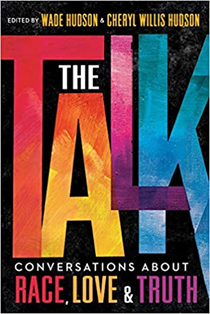

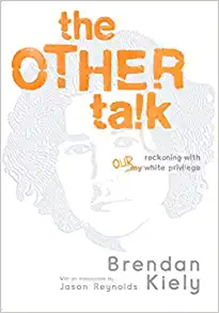

“The Talk” seems to have become more needed than ever in the past few years. Wade Hudson and Cheryl Willis Hudson are the editors of the anthology The Talk: Conversations About Race, Love & Truth, and Brendan Kiely is the author of The Other Talk: Reckoning With Our White Privilege. I owned and had read The Talk already when I learned that Kiely had The Other Talk forthcoming this September. I immediately thought it would be incredible to juxtapose these two books and have an important discussion.

Lisa Krok: It is so wonderful to be able to have these very important conversations with you and with each other. Wade and Cheryl, what led you to compile these valuable and necessary stories in your anthology?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Wade Hudson/Cheryl Willis Hudson:

In thinking about “The Talk” as a necessary conversation between most Black parents and their children, we realized that there are many kinds of talks that others had as well. Learning how to navigate the world with confidence and caring is an essential survival skill made more difficult by the challenges marginalized people often face. Who better to share these stories, these lessons than children’s book creators with first-hand knowledge and experience?

How do you talk about things that may be uncomfortable to discuss? How do you stay safe? How can you feel secure within your own body and personal space? How does one avoid racial profiling, police brutality or deal with bullying or sexual harassment? What can young people do when faced with systemic racism, name calling, religious intolerance, and cultural stereotypes? What about confronting the issue of white privilege? And how can these lessons, these necessary “talks,” be shared with children and young people?

That’s what The Talk tries to answer. We believed it was necessary to offer these lessons, these “talks” across social and cultural lines.

LK: Yes, I wholeheartedly agree with the necessity of these talks! Brendan, can you share a bit about the Two Americas you saw while touring with Jason Reynolds, and how that influenced your writing of this book.

Brendan Kiely:

First of all, I’m honored and grateful to be here and to be a part of this conversation with you, Wade and Cheryl. I wrote The Other Talk after listening to many, many people of the Global Majority talk about “The Talk”they had in their families growing up—the myriad manifestations of “The Talk” Cheryl and Wade’s anthology highlights so beautifully. As their anthology points out, there are many different kinds of “Talks”, especially as to how racism affects people’s lives, but, as Jason and I have discussed over the years, there isn’t often a talk white families have that speaks clearly and directly about the privileges white families experience because of racism in America. And so I wrote The Other Talk to try to join the conversation Black families, Indigenous families, and so many families of the Global Majority have been having for so long.

So, Jason and I met while touring our debut novels. We were thrilled and grateful, because our publisher was kindly sending us to conferences and festivals all over the country. We were having a ball—but it was also impossible not to notice that, as a Black man and a white man traveling side-by-side, we were having different experiences too. It was impossible for me not to notice the magnitude of racist undertones—the suspicious glances, the unkind greetings, the extra pat downs in security—all happening to Jason, not me. I talk more in depth about those moments in the book, but just as it was impossible not to notice what was happening to Jason as we traveled the country, it became startlingly impossible for me to not notice what was happening to me too. From a certain point of view, I recognized that conversely to Jason, I was experiencing welcoming smiles and zero suspicions as we walked into bookstores, schools, or through airports or hotel lobbies. People assumed I belonged wherever we were. It was as if we were experiencing (as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. suggested back in 1968) “two Americas”, two different Americas. I’m not saying everything was terrible; like I said, he and I were having a blast—and I think it is really important to stress that, too—but racism undeniably affects life for all of us in America. It affects us in different ways, however, and I began to think about how this pervasive racism affects my life by undergirding my life with social privileges.

And this is why I wanted to write The Other Talk: to help inspire white people like me to engage in conversations about racism in America by listening more, and learning more, and becoming more self-aware about how privilege affects our lives, and to feel more motivated to act and co-construct a more racially just America in solidarity with people of the Global Majority, who have been having these conversations for such a long time.

LK: I am so glad you took this on, Brendan!Wade and Cheryl, how did you go about selecting the contributors to your anthology, and how do the varied forms/styles/illustration mediums add meaning to the individual stories?

WH/CWH:

We asked BIPOC friends in the industry whose work we admired and respected to contribute to The Talk. They had a variety of stories to share from their own personal experiences. Meg Medina for example, wrote about the advantages of being bi-lingual but being discriminated against because of it; Grace Lin wrote a letter to her daughter about recognizing the objectivism of being called a “China doll;” Daniel Nayeri wrote about the weight of silence in communicating across cultures and the value of not talking; Duncan Tonatiuh wrote about a school visit where a student actually asked the question “Why Are There Racist People?” Tracey Baptiste in her essay, “TEN,” gave advice to her preteen on how to respond if being stopped by the police when driving while Black. Whether written as a poem, essay, prose, or letter or created in cartoon/graphic digital format or drawn via a realistic watercolor, the diversity of writers and illustrators expressed thought provoking situations that young people find themselves in. The end result was a powerful and complementary balance of text and images.

LK: It is truly a glorious amalgamation of varied stories and styles!Brendan, your anecdote with the strawberry Nesquick really stood out to me. Could you share that please?

BK:

The Strawberry Nesquik story is a starker and more devastatingly tragic example of the “two Americas” I mentioned before, in that it juxtaposes Jordan Davis’s life with my own, but what I think is at the heart of the story is a deeper understanding of the “other America,” the “privileged America,” in which I live. I think some people hear the term “white privilege” and they immediately think about all the ways in which they are not “privileged” (not rich, not living in a fancy house, not taking vacations to far flung corners of the world), or they think that applying that word to their life takes away from all their “hard work.” This is why, in the book, I use the example of the benefits my grandfather made use of in the GI Bill when he returned from WWII. He had access to opportunities (higher education; further, specialized degrees; home loans; brokers who would show him real estate in areas where the property value was rapidly increasing). Everything he achieved he did through hard work—no doubt about that—and it is also true that everything he achieved he had access to in a way many, if not most, veterans of the Global Majority in America did not have access to. Did he work hard? Yes. Was he also privileged with more access to opportunity? Also yes. He benefited from the effects of systemic privilege, you might say; and two generations later, I too benefit from his (and my own) systemic privilege. But racism is systemic and also interpersonal—and so too is privilege. So not only have I benefitted from multi-generational systemic privilege, the Nesquik story highlights just how privileged my interactions are with other people I encounter in my life—store clerks, law enforcement, my teachers, etc. Because the word “privilege” leaves such a bad taste in some people’s mouths, the poet and scholar Claudia Rankine replaces the phrase white privilege with white living—it’s just the experience of living as a white person in America. And, in the book, I try to use many, many examples from my own life to spotlight and explain why so many of those everyday experiences of my life living as a white person in America are in fact privileged.

LK: You delineated white privilege perfectly! It is indeed misunderstood by many.Wade and Cheryl, is there a particular story in your anthology that stands out to you personally, and why?

WH/CWH:

All the entries are special to us because they spotlight a particular aspect of each creator’s experience or a particular concern or challenge. This adds to the breadth of the book. Adam Gidwitz’s story “Our Inheritance” is important to us because it is told from the perspective of a white writer. Often, anthologies or books that deal with social justice issues focus on the victims and imply that the victims must find the answers to the challenges presented. We believe that equality, social, economic and political justice, can only be achieved when all of us, together fight to achieve them. Adam’s piece is crucial because it brings everyone to the table for this important discussion, not just those from BIPOC communities.

LK: Absolutely! It is so important for allies also learn and do the work, rather than placing that burden on the victims. Brendan, I was fascinated by your statement that, “race has no basis in biological fact”. Can you elaborate on this, please?

BK:

I always return to Ta-Nehisi Coates’s line “race is the child of racism, not the father.” In other words, “race” is a social construct. I think it is important to reinforce just how strongly biologists want the rest of us to understand this. For example, this is from the American Association of Biological Anthropologist’s Statement on Race & Racism:

Race does not provide an accurate representation of human biological variation. It was never accurate in the past, and it remains inaccurate when referencing contemporary human populations. Humans are not divided biologically into distinct continental types or racial genetic clusters. Instead, the Western concept of race must be understood as a classification system that emerged from, and in support of, European colonialism, oppression, and discrimination. It thus does not have its roots in biological reality, but in policies of discrimination. Because of that, over the last five centuries, race has become a social reality that structures societies and how we experience the world.

I apologize for the long quote, but I thought the whole paragraph was worth highlighting because I elaborate on these ideas, and how they relate to my life specifically, in the book.

The subtitle of my book is “reckoning with our white privilege.” To me, I think being clear and honest about how those “policies of discrimination” throughout history unequivocally impact our lives today is a vital part of the conversation (the “other talk”) white families like my own can engage in more deeply and discuss with young people. As the young, eight-year-old white girl from Traverse City, MI quoted in the Washington Post explained, although learning about racism in second grade made her feel bad, it also made her motivated to want to do something about it. In essence, learning about the truth of racism and privilege made her want to learn more so that she could do more—and I think we owe it to her and all young people out there to try to learn more, listen more, and act alongside them.

Many thanks to Wade, Cheryl, and Brendan for this essential conversation, which is just the beginning! Teen librarians, if you happen to be at the YALSA Symposium in Reno this November, please join us for a more in-depth conversation about these two books. Let’s Talk!

The Talk: Conversations About Race, Love & Truth is available now from Crown Books for Young Readers.

The Other Talk: Reckoning With Our White Privilege releases September 21 from

Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

An author and publisher, Wade Hudson is president of Just Us Books, Inc., an independent publisher of books for young people. Among his 30 published books are the middle grade anthologies, We Rise, We Resist, We Raise Our Voices and The Talk: Conversations About Race, Love & Truth, coedited with his wife, Cheryl; AFRO- Bets Kids: I’m Going to Be; Journey, a poetry collection; and Defiant, Wade’s memoir of growing up in the Jim Crow South at the height of the civil rights movement. Wade has received the New Jersey Stephen Crane Literary Award, the Ida B. Wells Institutional Leader-ship Award, the Madam C. J. Walker Legacy Award, and a CBC Diversity Outstanding Achievement Award.

Cheryl Willis Hudson is an award- winning children’s book author and cofounder with her husband, Wade Hudson, of Just Us Books, Inc., an independent publishing company that focuses on Black-interest books for young people. Her published titles include the classic AFRO- BETS ABC Book; Bright Eyes, Brown Skin; and Brave. Black. First.: 50+ African American Women Who Changed the World. She and Wade co-edited the middle- grade anthologies We Rise, We Resist, We Raise Our Voices and The Talk: Conversations About Race, Love & Truth. A member of the PEN America Children’s and Young Adult Books Committee, Cheryl has been honored with the Madam C. J. Walker Legacy Award and Children’s Book Council Diversity Outstanding Achievement Award.

Brendan Kiely is The New York Times bestselling author of All American Boys (with Jason Reynolds), and three other novels, and most recently a nonfiction book, The Other Talk: Reckoning with Our White Privilege. His work has been published in over a dozen languages, and has received the Coretta Scott King Author Honor Award, the Walter Dean Meyers Award, and ALA’s Top Ten Best Fiction for Young Adults. A former high school teacher, he is now on the faculty of the Solstice MFA Program. But most importantly, he lives for and loves his wife and son.

Lisa Krok, MLIS, MEd, is the Adult and Teen Services Manager at Morley Library and a former teacher in Cleveland, Ohio. She is the author of Novels in Verse for Teens: A Guidebook with Activities for Teachers and Librarians (ABC-CLIO). She reviews YA for School Library Journal, blogs for Teen Librarian Toolbox, and her passion is reaching marginalized teens and reluctant readers through young adult literature. Lisa has served on both the Best Fiction for Young Adults and Quick Picks for Reluctant Reader’s teams. She can be found being bookish and political on Twitter @readonthebeach.

Filed under: Teen Issues

About Karen Jensen, MLS

Karen Jensen has been a Teen Services Librarian for almost 30 years. She created TLT in 2011 and is the co-editor of The Whole Library Handbook: Teen Services with Heather Booth (ALA Editions, 2014).

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Moral Dilemma of THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT