Mercury in Their Veins: Louisa May Alcott, Edgar Allan Poe, and other luminaries share a curiously poisonous history, a guest post by Chandra Prasad

Recently I became aware that a town called Danbury, Connecticut, which is about a thirty-minute drive from my house, used to be known as the “hat city of the world” owing to the huge number of hatmakers who lived and worked there. Sadly, Danbury also had a darker reputation in the mid-19th century. Many of its hatmakers had the “Danbury Shakes.” Neither dance craze nor ice cream drink, the Danbury Shakes was a medical symptom that the hatmakers developed after continuous exposure to mercury. Making felt for the hats involved a process called carroting, which used an orange-colored solution containing mercury nitrate to turn animal fur into felt. The hatmakers inhaled the toxic mercury vapors and eventually developed the Danbury Shakes: tremors, slurred speech, and, invariably, a descent into madness and death. Both the Mad Hatter from Alice in Wonderland and the expression “mad as a hatter” originate from mercury poisoning.

I was surprised I hadn’t encountered Danbury’s history sooner, as I extensively researched the history of mercury while writing my new YA novel, Mercury Boys. In the book a group of teen girls figures out a way to time travel in their dreams by way of liquid mercury, old photographs, and a little magic. The girls form a secret society to guard their exciting discovery, but it’s not long before their clandestine club turns—literally and figuratively—into a toxic bubble of lies, jealousy, and revenge. The old photos in the novel are daguerreotypes, a popular type of photography in the mid-19th century that required the use of liquid mercury. Daguerreotype-makers then were often amateur chemists since they needed an extensive knowledge of chemistry to create the fragile and time-consuming black-and-white images. But they weren’t the only ones who dabbled in the silvery element that has long been both beneficial and devastatingly dangerous.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The ancient Chinese and Hindus knew about mercury, nicknamed quicksilver, the only metal that is liquid at room temperature, since at least 1500 B.C. Substantial quantities of mercury have been found below Quetzalcoatl, the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, the third largest pyramid at Teotihuacan, a pre-Columbian site in Mexico. Mercury has been discovered in ancient Egyptian tombs, too. This is not surprising since mercury is so reflective that it’s mirror-like, and mirrors were (and are) considered a link to the supernatural world or portals through which souls can move in many cultures and religions. Daguerreotypes, which are also highly reflective, are sometimes called “mirrors with a memory.” Annabeth Headreck, a professor and expert on Teotihuacan and Mesoamerican art, hypothesizes that the silvery stream of mercury under the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, might have looked like “an underworld river, not that different from the river Styx…the entrance to the underworld.”

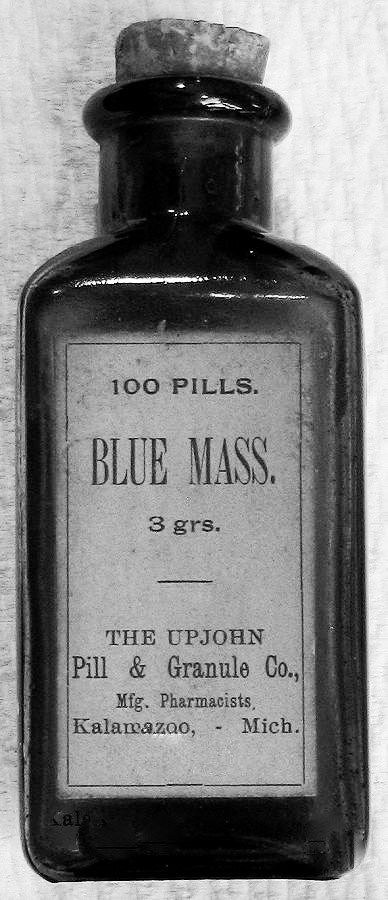

It’s not clear if Teotihuacan people understood the serious ramifications of mercury exposure. But other civilizations did. Ancient Romans sent their least valued citizens—slaves and criminals—to mercury mines, knowing that mercury poisoning would kill most in a brief period of time, sparing the need for formal execution. Strangely, the knowledge that mercury causes extensive neurological and gastrointestinal damage seems to have escaped medical practitioners from the 17th through 19th century in America. Doctors then commonly prescribed a cobalt-colored pill called “blue mass,” which contained licorice root, rose water, honey, sugar, and copious amounts of mercury. Blue mass was prescribed (uselessly) for decades for syphilis, but it later became a kind of cure-all, dispensed for everything from depression and constipation to stomach worms and toothaches. Even as late as 1920, parents were unwittingly poisoning their children with mercury-laden products marketed in the name of better health. “Dr. Moffett’s Teethina Powder” was a popular remedy for teething babies. The problem? It contained calomel, also known as mercury chloride. Only in the 1950s did doctors realize why the tots given calomel had displayed such a wide and horrifying array of symptoms, from severely chapped skin to wild thrashing.

The most famous American to take blue mass was no doubt Abraham Lincoln. Throughout his life Lincoln suffered from bouts of depression. For this, or perhaps for constipation (historians debate which ailment), Lincoln regularly took blue mass pills. His consumption likely affected his behavior. In fact, it’s theorized that his erratic, and even violent, outbursts documented in the years before the Civil War (from April 12, 1861 to April 9, 1865) were probably due to mercury poisoning. A study conducted by Norbert Hirschhorn, Robert G. Feldman, and Ian Greaves, published in a 2001 issue of Perspectives in Biology and Medicine involved the painstaking recreation of blue mass pills. The researchers discovered that Lincoln’s daily dose of mercury would have been almost 9000 times higher than what the EPA considers safe. Fortunately for America, Lincoln apparently laid off blue mass during the Civil War, when he displayed a much cooler head (symptoms of mercury poisoning in adults are often reversible).

Many other famous people also took mercury for medicinal reasons. While serving as a Union nurse in 1862, Clara Barton, the founder of the Red Cross, was treated with mercury chloride (calomel) when she contracted typhoid fever. She later wrote in a letter on the experience: “I was never ill before this time, and never well afterward.” Charles Darwin, too, likely consumed calomel and blue mass. That might explain why the once intrepid explorer was riddled with ailments and seldom left his home during his last forty years of life. President Andrew Jackson, who signed into law the Indian Removal Act, which violently relocated Native Americans from their land and led to thousands of deaths between 1830 and 1850, also took calomel regularly.

While researching Mercury Boys, I learned that some of the most renowned 19th century authors also ingested mercury. Edgar Allan Poe drank heavily and dabbled in opium, among other vices. Hair samples reveal that he also had mercury in his system when he died. Perhaps he took mercury to treat a documented case of cholera. That same mercury could help explain Poe’s vivid hallucinations and truculent behavior in the days prior to his death on October 7, 1849. Louisa May Alcott, the beloved author of Little Women, took mercury via calomel after contracting pneumonia and typhoid fever as a nurse during the Civil War. For the rest of her life, she experienced an array of painful symptoms, although some may have been due to lupus, which historians also say she could have had.

Nowadays we mostly associate mercury with old thermometers and contaminated fish. But the element’s history is rich in lore and legend, dreams and death, unexplained symptoms and strange superstitions. It’s no wonder, then, that I found this history perfect fodder for my novel Mercury Boys, which blends the above with the modern-day trials and tribulations of female adolescents navigating an ever-shifting sea of social media and complex teen dynamics. Perhaps a character in Mercury Boys, the roguish, real-life 19th century inventor Robert Cornelius, best explains mercury’s magnetism when he says, “I became addicted to the lure of mercury, and I’m not the first. Mercury’s the most fascinating of the elements. Beautiful. Mysterious. Dangerous.”

Meet the author

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

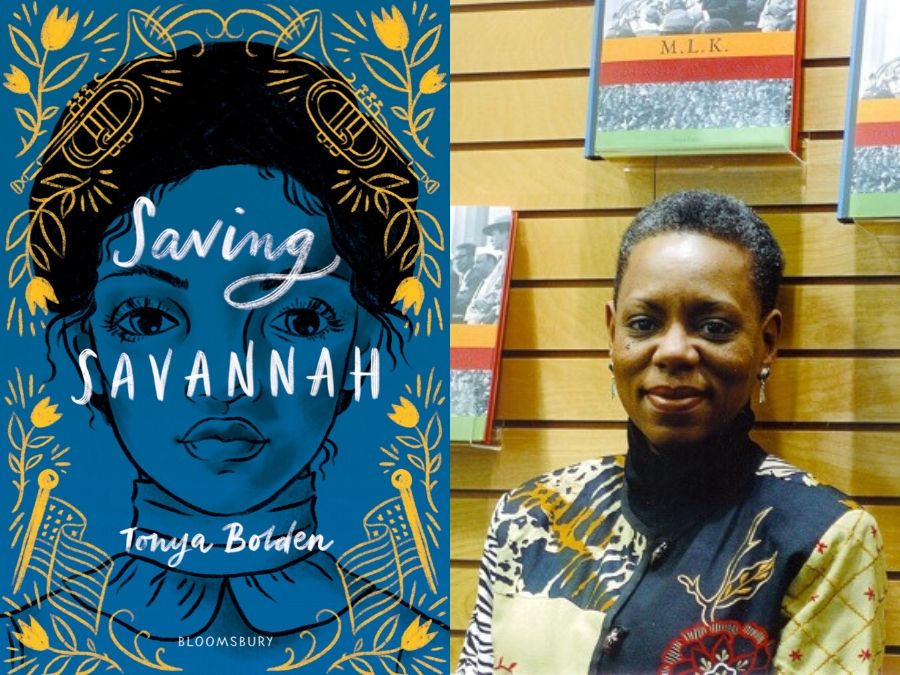

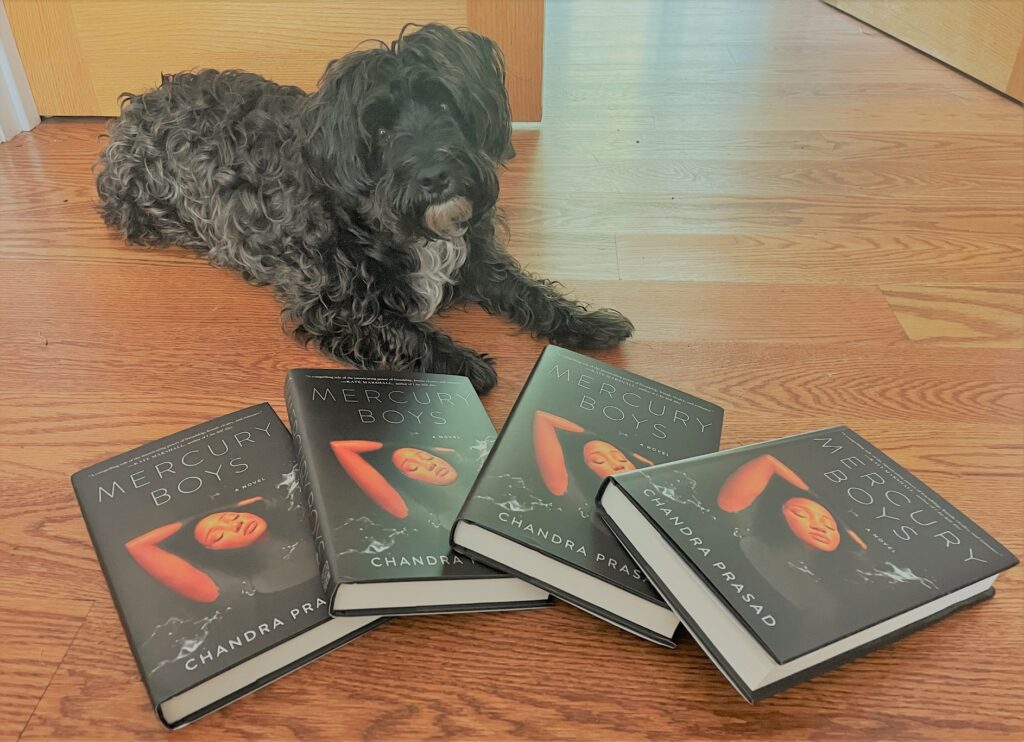

Chandra Prasad’s second young adult novel Mercury Boys, published by Soho Teen, arrives on August 3, 2021.This low-fantasy historical thriller follows teen girls who discover that they are able to visit the long-deceased people in daguerreotypes, old photographs that were developed using liquid mercury. Carrie Firestone, author of The Loose Ends List, says, “Mercury Boys has daguerreotypes and dashing strangers, hiding spots and crossed lines. It’s full of secrets and fraught with danger. Ultimately, it’s like mercury itself—mesmerizing, terrifying, thrilling, and dangerously beautiful.”

Prasad’s other works include Damselfly, a female-driven YA adventure novel used in schools as a parallel text with Lord of the Flies; On Borrowed Wings, a Connecticut Book Award finalist; Death of a Circus, a novel Booklist calls “richly textured and packed with glamour and grit;” Breathe the Sky, a fictionalized account of Amelia Earhart’s last days; and Outwitting the Job Market, a guide for young jobseekers. Prasadis the editor of—and a contributor to—Mixed, the first-ever anthology of short stories on the multiracial experience. Her shorter works have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The New York Times Magazine, The Week, New Haven Noir, Teen Voices, and numerous literary, arts, and poetry journals.

Author’s Social Media

Mercury Boys website: www.mercuryboys.com

Author website: www.chandraprasad.com

Twitter: chandrabooks

Instagram: chandraprasadbooks

TikTok: chandraprasadbooks

About Mercury Boys

History and the speculative collide with the modern world when a group of high school girls form a secret society after discovering they can communicate with boys from the past, in this powerful look at female desire, jealousy, and the shifting lines between friendship and rivalry.

After her life is upended by divorce and a cross-country move, 16-year-old Saskia Brown feels like an outsider at her new school—not only is she a transplant, but she’s also biracial in a population of mostly white students. One day while visiting her only friend at her part-time library job, Saskia encounters a vial of liquid mercury, then touches an old daguerreotype—the precursor of the modern-day photograph—and makes a startling discovery. She is somehow able to visit the man in the portrait: Robert Cornelius, a brilliant young inventor from the nineteenth century. The hitch: she can see him only in her dreams.

Saskia shares her revelation with some classmates, hoping to find connection and friendship among strangers. Under her guidance, the other girls steal portraits of young men from a local college’s daguerreotype collection and try the dangerous experiment for themselves. Soon, they each form a bond with their own “Mercury Boy,” from an injured Union soldier to a charming pickpocket in New York City.

At night, the girls visit the boys in their dreams. During the day, they hold clandestine meetings of their new secret society. At first, the Mercury Boys Club is a thrilling diversion from their troubled everyday lives, but it’s not long before jealousy, violence and secrets threaten everything the girls hold dear.

ISBN-13: 9781641292658

Publisher: Soho Press, Incorporated

Publication date: 08/03/2021

Age Range: 14 – 17 Years

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on BlueSky at @amandamacgregor.bsky.social.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Newbery/Caldecott 2026 Spring Check-In

Remember (the) Maine: A Stroll Around Kittybunkport with Scott Rothman

5 Unlimited Access Digital Comics to Boost K–8 Reading | Sponsored

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

ADVERTISEMENT