TLT TURNS TEN: Ten Great Guest Posts

This week Teen Librarian Toolbox turns 10. TEN! To celebrate, I’ve got lots of ten-themed posts coming. Up today: ten great guest posts. We are lucky that we get so many wonderful guest posts from authors, teachers, and librarians. From our yearlong projects to reading lists to posts related to authors’ new books, there’s always something great being shared by others on our blog. You can search the blog for guest posts and catch up on some that you may have missed! Meanwhile, here are snippets of and links to ten that have stuck with me.

From the post:

Being anti-racist is going to take more than a few weeks of hyping certain books and creating aesthetic Instagram posts. It’s going to take a fundamental shifting in the way we all view and interact with the world. It’s going to take interrogating the way each and everyone of us has allowed the structures of this industry to function unjustly for so long.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The work does not and cannot end with buying a copy of a Black author’s book or even blacking out an entire bestseller list, though that is an excellent start. The work will end when Black and other marginalized voices are no longer working in this industry at a structural disadvantage. And it’s going to take every single one of us at every level of the publishing hierarchy to make sure this change stays for good.

We all need to keep showing up for Black voices and Black lives, even when it’s no longer on trend to do so.

Monsters united can never be defeated: sentimental queer horror YA, a guest post by Hal Schrieve

The year I turned fourteen, I came out to my parents as transgender. In 2010, as a young teenager, with Gender Identity Disorder still written into the DSM as a disease, I knew that my eventual medical transition would require doctors’ notes and assessments in order to proceed. But my parents, wearing a look of inscrutable fear, initially took me to therapists with the stated hope that we as a family would work something out that didn’t involve me actually ever transitioning.

Eventually, all the doctors my parents took me to, even those most sympathetic to my parents, began to reach the consensus that I was in fact a transsexual. That, the doctors and therapists agreed, meant my parents had to move to the next healthy stage in raising a trans child: mourning my death.

This is standard advice, advice that the parents of trans children have gotten from well-meaning therapists for decades. My inexpert Cut Rite haircut, abbreviated name, the desire to to put testosterone into my body and surgically modify my chest, and, not least, my expression of my desire for romantic and sexual contact with gay men—meant that the child my parents had raised was dead. My parents had lost their shot at something. Therapists phrased it in different ways, describing the dead girl who I was not as a child of expectations, or dreams, as someone who had existed and as someone who had never existed. But again and again, the living teenager in front of my parents was ignored in favor of the theoretically dead girl I had replaced. My parents were given permission to ignore my distress, the bullying I was facing, the discrimination I faced from my school, the lack of information I had about what my future might hold, so they could grieve and adapt slowly to life without their daughter—though I was alive, and their real daughter, my little sister, was right in front of them and living too. For a period of just over a year, and maybe long beyond that, I became undead, unknowable, invisible to the people who were supposed to protect me.

MHYALit: This Book Will Save Your Life, a guest post by author Kathleen Glasgow

“Mommy,” I said, my voice sounding strange and far from me. “If you don’t take me to the hospital, right now, I am going to kill myself.” I was sixteen. I meant it.

What followed was my mother slipping into robot-mode. She made calls, she smoked cigarettes, she argued with my father on the phone, and by the end of the day I was a new patient at small and somewhat seedy psychiatric hospital. I was lumped in with adults. There was no separation by disorder, age, or “problem.” As one of my new colleagues put it during a dinner of slimy green beans and something resembling partially-heated Salisbury Steak, “We all fucking crazy in the same fucking crazy salad. You the tomato, she’s the lettuce, I’m the damn dressing.”

I had never felt so safe in my entire life.

When I was younger, growing up in a house filled with violence and fear, I found my solace in books. I read and re-read books obsessively, looking for anything that could lift me away from the darkness of my daily life. I should have been a prime candidate for fantasy or science fiction, but that wasn’t my thing. I latched onto anything that even vaguely resembled what was happening in my life and at that time, the queen of all things realistic was Judy Blume. Being bullied at school? Blubber became my tome. Having body and anxiety problems? Deenie. Curious about sex? The holy grail was, of course, Forever. Fuck the whole tesseract business (though that was cool, too): I latched onto A Wrinkle in Time for Meg Murry, the lonely outcast.

When I found my mother’s 1954 copy of The Catcher in the Rye, though, Holden Caulfield spoke to me like no one else had. Here was someone who was clearly depressed, suicidal, afraid of the world, afraid of himself. I still have that book. I still reread that book, every year, because it was the first book that taught me that I was not alone. I saw myself in Holden. It was a salve, a balm, for a long time.

Elana: Isabel, I think it’s interesting that both of our titles–GABI: A GIRL IN PIECES, and WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF–hone in on how girls are dissected by themselves, by their families, by their friends and their boyfriends, by society. Why is it, do you think, that girls are such consumable products?

Isabel: Well, I think it has to do with the fact that we live in a capitalist patriarchy where we are taught that everything is consumable. Women are often not seen as autonomous, young women especially and girls less so. We are always thought of in relation to someone else, defined by what our purpose is in that relationship–daughter, sister, mother, girlfriend, mistress, wife, and so on. Those roles are seen as both consumable and disposable. And because we are often not seen as autonomous, as having our own worth, that seems to translate into our voices, our bodies, our time, being assumed to be in the service of others–for pleasure, reassurance, guidance, emotional support, nurturing, etc–and for their consumption.

Nina is girlfriend until Seth decides she is not, and doesn’t even tell her. Nina’s dad had one wife and disposed of her and then took on Nina’s mom. And in my book, Gabi’s mom feels Gabi should look a certain way because she needs to fill the role of desirable young woman to eventually become wife. Is she concerned that Gabi should go to college? Yes, but being desirable seems to take precedence sometimes.

Some of it may be rooted in fear. I know that one of my mom’s biggest fears is that I end up alone. And it has been this way since I was a teenager–being married was a top priority. Now that I am no longer with husband, I find that she still worries about that. But this goes back to having worth attached to how much we are worth to others–or, in other words, how much they can take.

I have been keeping an eye on books featuring queer characters in religious contexts for the last decade. When I was in my undergrad, I started on a directed study on books with LGBTQ content. My supervisor asked me about the direction in which I was hoping to go, and at the time I wasn’t entirely sure. Looking back at my own past and my history as a gay man within the Christian church, I wondered how, if at all, such experiences were being discussed in books for young readers. Keep in mind that only ten years ago, it was still difficult to find much in the way of LGBTQ literature for YA audiences, so trying to find religious representation within that limited subgenre felt at first like an impossible task. It certainly took a lot of effort to find materials, but I came across a few examples, and some from larger publishers, too. I discussed a number of these in more detail in my previous post. Here are some main points to refresh your memory:

- Early LGBTQ YA tends to frame Christianity (or any major religion really) as the enemy, often in the form of a religious leader preaching fire and brimstone for any and all non-normative genders and sexualities (Nothing Pink, Desire Lines);

- Queer teens often sent away to camps for degayification (Caught in the Crossfire, Thinking Straight, The Miseducation of Cameron Post);

- Earlier narratives often include long and didactic passages with characters debating scripture in an effort to show which side is right (Nothing Pink, The God Box, Gravity);

- The novels were basically able to be split into two categories: novels of reconciliation (characters are able to reconcile queerness and spirituality, though not very often), and novels of abandonment (characters have to abandon either their faith or their sexuality in order to survive, and this is the more common trope.)

Coming of Age and the Reality of Others, a guest post by Sara Zarr

Is what we call “love” the experience of people being who we need them to be, and meeting our needs and expectations? Or is it accepting those closest to us in spite of their limitations and mistakes? Does the latter type of love have its limits and, if so, where are those limits? These aren’t questions that most adults I know have resolved, but we start becoming aware of them in our adolescent transition from childhood towards adulthood.

The context of Murdoch’s quote is an essay attempting to answer the question, “What is art?” She’s joining Tolstoy, Kant, and others in an ongoing conversation around this question, and for her, love and art and morality are all bound together in this issue of reality in a broader sense.

Personally, my allegiance in writing has always been to reality–which I don’t mean in a genre sense, as fantastical stories can have an allegiance to truth and realism can be false. What I mean is that I try to see things as they are and write about them from that clarity of vision. Murdoch writes, “We may fail to see the individual because we are completely enclosed in a fantasy world of our own into which we try to draw things from outside, not grasping their reality and independence, making them into dream objects of our own. … Love [is] an exercise of the imagination.”

MHYALit: On Medication, a guest post by author Emery Lord

Let’s get the personal info out of the way: I have been healthy on and off medication; I have been unhealthy on and off medication. I have chosen medication, and not medication. Because my health is a dynamic relationship—me and my mind and body, it means changing my approach sometimes. And so I certainly don’t think there is a universal right or wrong way to treat mental illness. Just right for you.

While I was researching When We Collided, one of the first questions I asked a doctor was if teens failing/refusing to take prescribed medication is as prevalent as it seems? (The refusal to take medicine or having very negative feelings toward medication is a frequent storyline in young adult media.) Yes, she said. But not just mental health medication. A very common ER issue is diabetic teens who simply don’t monitor their blood sugar.

This stuck in my mind. I always thought teens not taking their anti-depressants or anti-psychotics was due to the stigma of mental illness. It’s a stigma that is scaffolded by movies and TV shows that portray medication almost exclusively as something that dampens your creativity and joie de vivre. And does that happen? Sure, to some people. But others will tell you that medication let them access their creativity and joie de vivre again. (I, for example, would say that.)

So, is it that there’s a stigma for anything outside “healthy” range? Or maybe it’s about acceptance? Is it that we haven’t fully accepted that something—anything—is wrong enough to need correction? Or even if we know medication might help—we so badly don’t want to need them?

What about you? Did you ever feel intimidated trying to write a funny book?

J: I didn’t necessarily feel intimidated while writing the book, because funny books are the only ones I know how to write, but when I was promoting my book, I noticed I was often the only woman on the funny book panels. What’s that all about? I really hope that changes quickly because the world is missing out on some awesome hilarious-girl content! Speaking of which, can you share your process of creating humor? How did you know a joke was landing?

A: I tested most of the quips on my husband, and he is very honest–brutally honest, sometimes, but that’s why he’s helpful! I also did lots of good old Youtube and Google searches about creating humor and humorous scenarios. We are so lucky to have a world of resources at our fingertips! And of course, I read other books for inspiration. Speaking of which, I’m curious: Who are some of your favorite funny female authors?

J: I’m a big fan of Dusti Bowling, Remy Lai, Lisa Yee, and Booki Vivat. They crack me up. What about yours?

A: First of all, YOU obviously haha. I also love Niki Lenz and all of the authors you mentioned above! If we are going to kick it old school, Judy Blume is fantastic. I grew up reading her Fudge series. Louise Rennison is a crack up and a total inspiration! And, of course, Renee Watson is an icon. Since it’s April Fools Day, I have to finish by asking: What was your favorite April Fools joke you’ve played?

MHYALit: It’s Okay Not to Be Okay, a guest post by author Claire Legrand

In fifth grade, I had my first anxiety attack.

I don’t remember what prompted me to ask my teacher if I could use the restroom, but I remember huddling in the stall, hunched over on the toilet, as nausea seized my tiny ten-year-old body. My skin broke out in sick chills. I scratched my arms and legs until they were covered in red marks.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

My thoughts raced with fear; I could not quiet my brain. I tried going to the bathroom, I tried throwing up. Nothing helped. I simply sat there and endured it until I felt well enough to go back to class.

Part of me was terrified by what had just happened. But I rallied and got through the day, dismissing that scary moment in the bathroom as . . . something. I had no idea what to call it.

I decided I was fine. I was still breathing, still standing.

I was fine. (I wasn’t fine.)

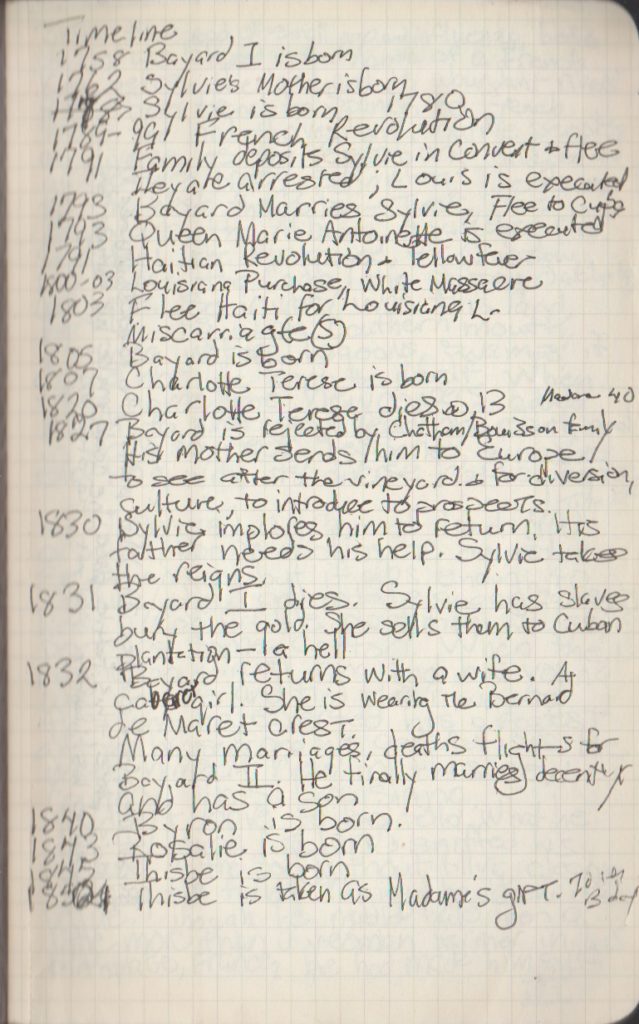

Historical Fiction in the Making, a guest post by Rita Williams-Garcia

Every novel relies on some research. A historical novel isn’t reliable without research and A SITTING IN ST. JAMES, demanded total immersion. I came to this story as a complete outsider. I was neither white, nor of French descent, nor Louisiana Creole. To gain the confidence of my readers, I took a year off from writing to do nothing but research: dig, read, uncover, and lastly, vet! Instead of researching while I wrote, I used the writing hiatus to hunker down in specific subjects: French Revolution, Haitian Revolution, Louisiana history, Louisiana Creole culture and language, sugar cane planting and production, West Point history and culture, mid-19th century portrait painting, among other subjects.

I filled up on mid-nineteenth century literature, to include French, Louisiana Creole and American readings. I combed through archives of narratives of survivors of slavery for testimonies of freed people from Louisiana. One gem I found helpful was a collection of Caribbean and Louisiana Creole proverbs from LacFadio Hearn’s GOMBO ZH’BES (green gumbo). I could see the smirks, the humor, and attitudes of the people. I got a taste of their lives and daily concerns.

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

This Q&A is Going Exactly As Planned: A Talk with Tao Nyeu About Her Latest Book

More Geronimo Stilton Graphic Novels Coming from Papercutz | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT