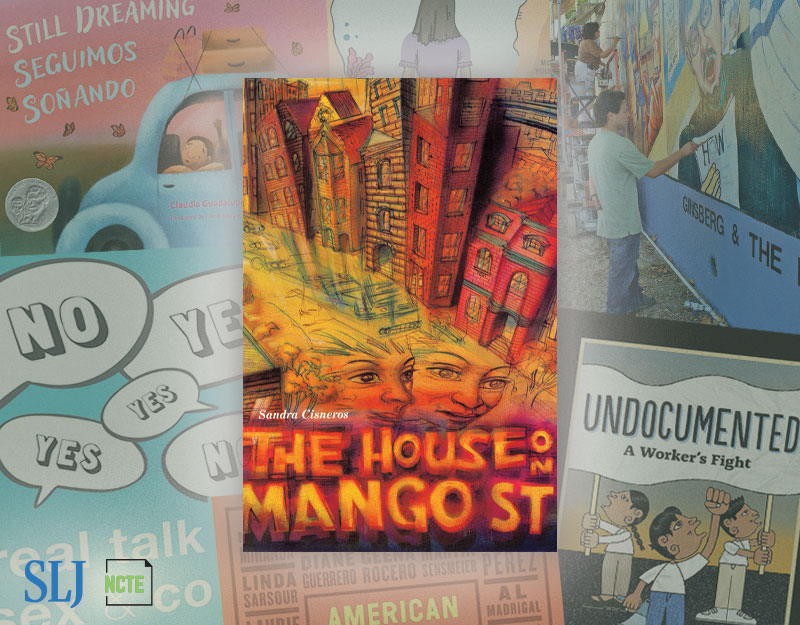

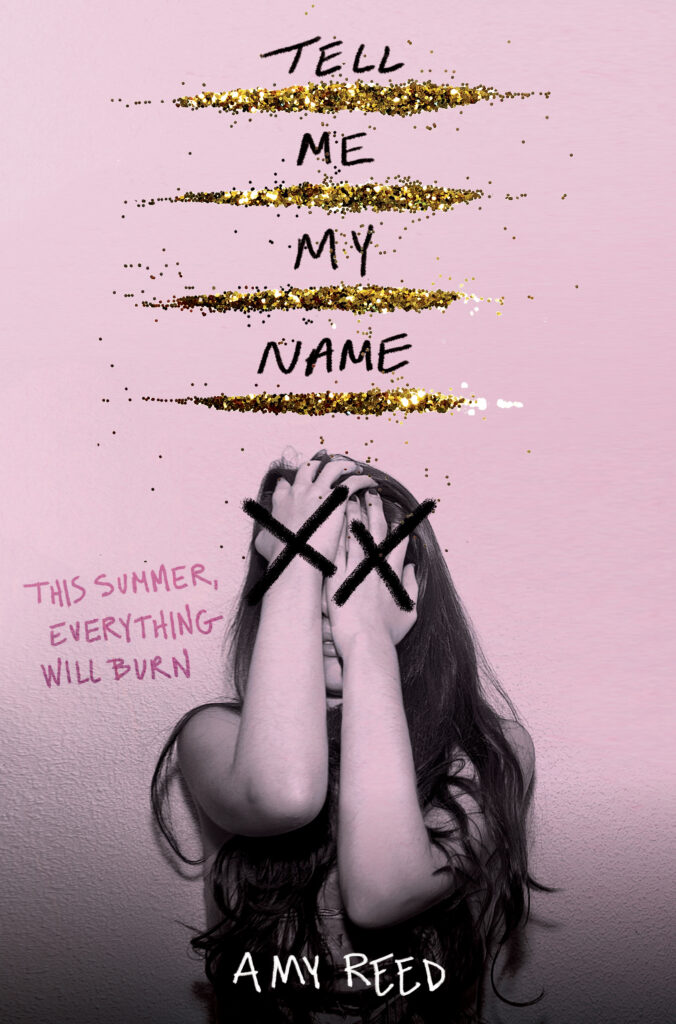

The Great Gatsby, Tell Me My Name, and Re-Imagining The American Dream, a guest post by Amy Reed

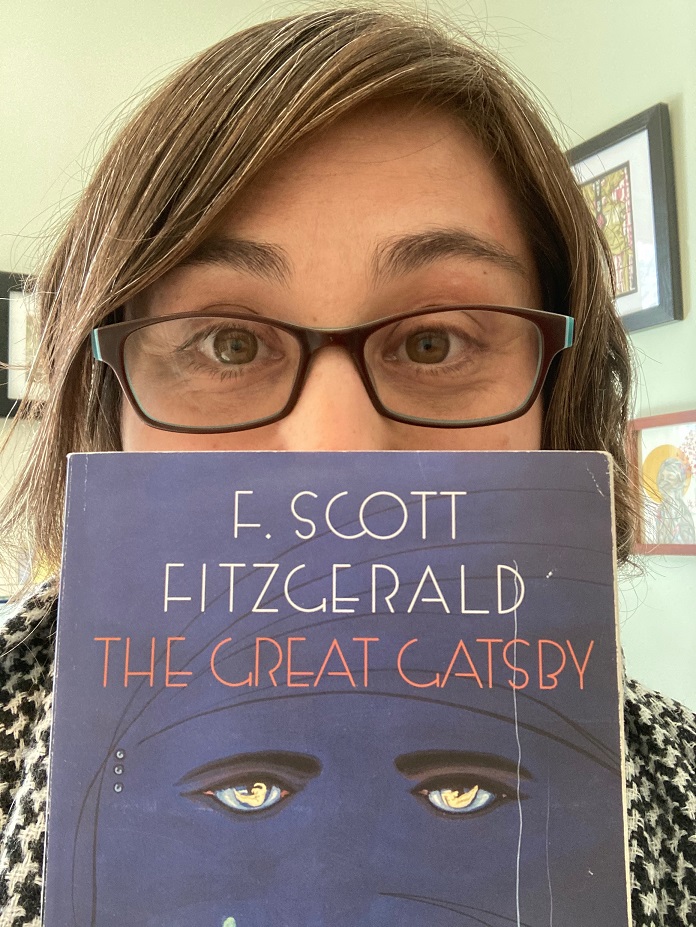

Nearly 100 years after its publication, The Great Gatsby is still considered by many to be the Great American Novel, and its depiction of the American Dream, that epic myth of the self-made man, is the one teens read year after year in English classes across the country. I vaguely remember reading it as a teen, hating Daisy and suspecting Nick was gay, and not understanding why Gatsby tried so hard to fit into a shallow world that so obviously didn’t want him in it.

More than anything, I remember wondering how I was supposed to see myself in the book. Was the American Dream Gatsby represented supposed to be my story, or was I supposed to identify with the female characters? My choices were bleak: either Daisy—pretty, weak, and shallow; or Jordan Baker, slightly more interesting because she was quick-witted, but mean and dishonest. Or was I supposed to be Myrtle, the mistress, the poor woman who never had a chance, the woman used and scorned by Tom Buchanan, the epitome of entitled, rich, white men?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

When I read it again as an adult a few years ago, something became clear to me: the book was not written for me. It was not written for my mother’s father, raised in the colonized Philippines, sold the myth of freedom and prosperity in his American textbooks, then confronted by the reality of racism when he got here at age sixteen and began his life as a farmworker, who died never having owned his own land. Perhaps it was written for my father, the self-made man, who did the most American thing possible and pulled himself up by his bootstraps out of a family plagued by generational poverty, neglect, and mental illness.

My father, who tells me he still sometimes feels surges of shame that seem to come out of nowhere, is still wracked by an old suspicion that everyone’s going to find out what a phony he is—the poor kid daring to think he has a place in a successful man’s world. He’s spent a lifetime trying to prove he deserves a place in that world, working sixty-hour weeks my whole childhood. Only now, at eighty-years old, is he finally giving himself permission to retire.

My father achieved the American Dream, but what did it cost him?

Jay Gatsby achieved the American Dream, and we all know what happened to him.

I wrote Tell Me My Name as an exploration of these questions: What is the American Dream depicted in The Great Gatsby? And does it include me? Does it include you?

It is the story of two young women fifty years in the future, living in an America tipping into disaster, in a world where all of the excesses of capitalism and industrialization have reached their breaking point. A teen girl who came from nothing—Ivy Avila, my Gatsby—has dared to claim a piece of the American Dream for herself. She is a girl, like so many of us, whose only esteem has ever come from other people telling her how much she’s worth. She lives in an America where class is even more stratified than it is now, where the only way to make it out of poverty is to be exceptional. It is the most American story there is.

It is my father’s story, who, by all accounts, is an exceptional man. It is my Filipino grandfather’s story, who made it further than many of the manongs of his generation, but whose ambition was always limited by his lack of formal education, his dark brown skin, and thick Cebuano accent; who then placed that ambition on his daughters who he instructed to get an education and marry white men. And then there’s me, raised to absorb this heritage of imposter syndrome. Poor white imposter. Immigrant imposter. The American Dream built on this bedrock of shame, of needing to prove your worth because you believe, deep down, you will never ever be enough.

I wrote Tell Me My Name to dive deep into this uncomfortable place. Ivy and Fern, my heroines, yearn to be seen and valued, to be told “You are enough.” But Ivy will not find it in fame and fortune or even romantic love, will never be able to drown out her shame with alcohol and drugs. And Fern will not find it in Ivy, cannot run from her own dreams with the distraction of being useful. There is another source, one that has nothing to do with all this noise outside, one that does not require another person, or a nation, to tell us who we are or what we should dream.

The American Dream of Gatsby, of my father, of my grandfather—this is not my dream anymore. It is a place that once you reach it, as Gatsby did, you realize there’s nothing actually there. For those in power, for those who come from lives already steeped in it—those Tom Buchanans of the world, or in my book, those Tami Butlers—it is a dream of further conquest. It is a dream built on entitlement and the hoarding of power and wealth. For many of the rest of us, it is a dream built on shame, on the fantasy of aspiring, like my grandfather, to take our place among the people who oppress us.

My question is this: How does the American Dream depicted in The Great Gatsby and Tell Me My Name—that dream of obsessive ambition, relentless striving, fame and fortune and accumulation of power and wealth—how does it get in the way of your own authentic dream?

What is the potential of your dream if you look beyond the lie that we are only as good as what we own, what we accomplish, what external validation tells us we are worth?

What can our dreams look like if we already believe we’re worth something?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I’ll tell you what my dream is. I want to spend as much time as I can on this earth loving and creating. I want to cause as little harm as possible. I want to do my part to reduce harm, in whatever small ways I can.

What I want, more than anything, is the peace of being enough.

I hope this small dream has a place in our collective American imagining. I hope your dreams, whatever they are, do too. In a time so fraught with confusion, suffering, and conflict, I have to believe there is a place for all of our dreams, even—and especially—the ones that challenge the version of the American Dream we have been taught.

Meet the author

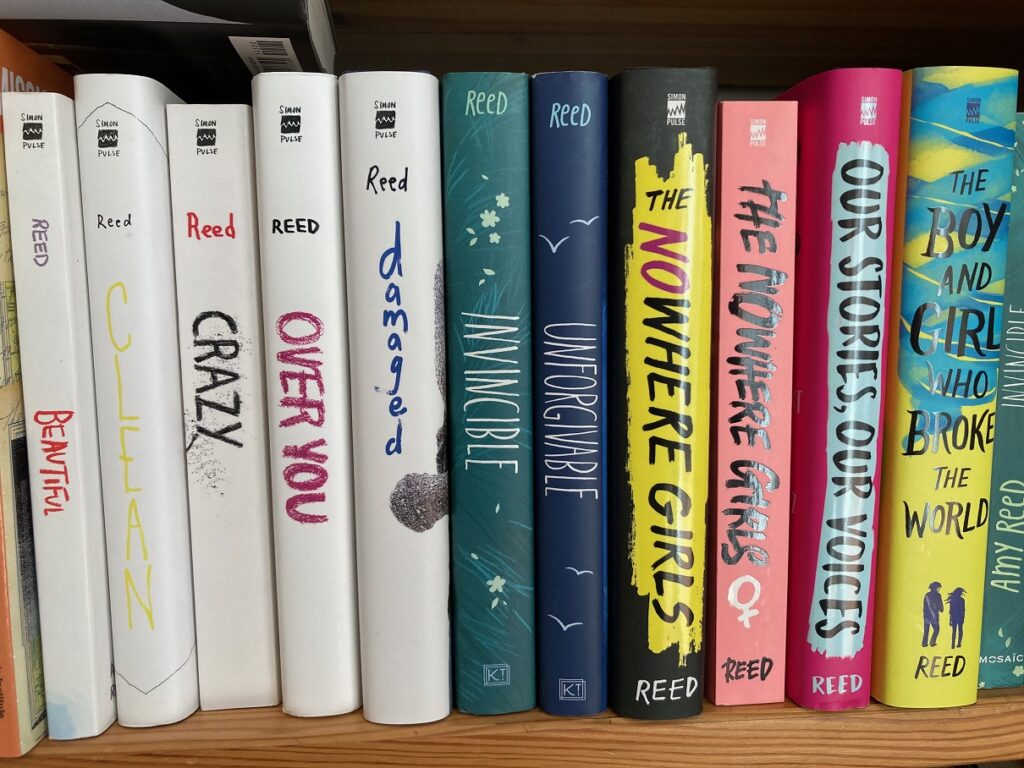

Amy Reed is the award-winning author of several novels for young adults, including The Nowhere Girls, Beautiful, and Clean. She also edited Our Stories, Our Voices: 21 YA Authors Get Real About Injustice, Empowerment, and Growing Up Female in America. Amy is a feminist, mother, and Virgo who enjoys running, making lists, and wandering around the mountains of western North Carolina where she lives.

Purchase signed copies of Tell Me My Name from Amy’s local indie, Malaprop’s Bookstore/Café

About Tell Me My Name

We Were Liars meets Speak in this haunting, mesmerizing psychological thriller–a gender-flipped YA Great Gatsby–that will linger long after the final line. On wealthy Commodore Island, Fern is watching and waiting–for summer, for college, for her childhood best friend to decide he loves her. Then Ivy Avila lands on the island like a falling star. When Ivy shines on her, Fern feels seen. When they’re together, Fern has purpose. She glimpses the secrets Ivy hides behind her fame, her fortune, the lavish parties she throws at her great glass house, and understands that Ivy hurts in ways Fern can’t fathom. And soon, it’s clear Ivy wants someone Fern can help her get. But as the two pull closer, Fern’s cozy life on Commodore unravels: drought descends, fires burn, and a reckless night spins out of control. Everything Fern thought she understood–about her home, herself, the boy she loved, about Ivy Avila–twists and bends into something new. And Fern won’t emerge the same person she was. An enthralling, mind-altering psychological thriller, Tell Me My Name is about the cost of being a girl in a world that takes so much, and the enormity of what is regained when we take it back.

ISBN-13: 9780593109724

Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group

Publication date: 03/09/2021

Age Range: 14 – 17 Years

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

Review of the Day: My Antarctica by G. Neri, ill. Corban Wilkin

Exclusive: Giant Magical Otters Invade New Hex Vet Graphic Novel | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT