In My Mailbox: Questions I Get About Collection Diversity Audits

Last week I did another presentation for School Library Journal about Collection Diversity Audits and I wanted to follow up and answer some of the most frequently asked questions that I get. If you don’t know about Collection Diversity Audits, I began doing these in 2015 and have been speaking about them since around that same time. I have blogged about it multiple times and I will share those posts with you at the end of this one.

In a nutshell: A collection diversity audit is kind of like doing an inventory and using the data that you get to determine how diverse your library collections are. The goal is to get some baseline data to help those who need to know what the collection looks like and what collection development librarians can do differently to curate the most diverse and inclusive collections possible.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

What are your percentage goals you work towards for your collection?

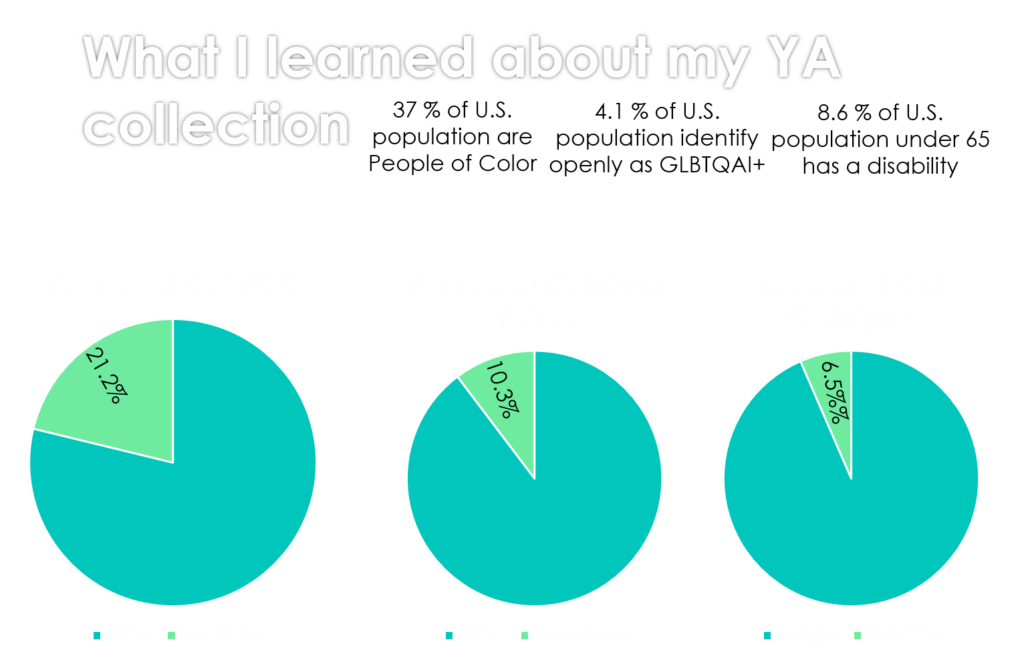

I don’t have a great answer to this question if concrete numbers are what you’re looking for. I think that what doing a collection diversity audit provides is data to help us as selectors to get a good baseline of where we are at and how we’re doing. I feel certain that most of us are not doing as good of a job as we think we are at developing diverse collections and collection diversity audits help us by providing us with baseline data to help us do some soul searching and self -assessment. By doing an audit we learn what our collections gaps are; what our personal or systemis biases are; and what areas we need to better focus on to be better at our jobs. The goal isn’t to work towards achieving certain numbers; instead, the goal is to collect measurable and usable data that helps us better focus our efforts and do some serious self/system analysis so that we can continue to grow and improve in intentional ways to serve our patrons.

I know that for some personality types this is a frustrating answer. I used to be that person who wanted to know exactly how long a paper had to be and I would love to be able to say that this number is the goal or an ideal collection. However, over time I have come to understand that that number doesn’t exist. If there was a number, it would vary to some degree depending on the local community served. I’ve worked in systems with multiple branches and each local community for each branch was different and that has to be taken into consideration when building collections. But what we do gain when we do a collection diversity audit is valuable insight into what our collections look like and how we can better improve the representation in our collections to help grow world citizens.

How Do You Know if Something is Own Voices?

The conversation surrounding Own Voices is valuable, evolving and sometimes tricky to navigate. Own Voices is a book written by an author who identifies with the representation within the book. The value in Own Voices is twofold. One, when a book is written by an Own Voices author it is less likely to have harmful stereotypes and more likely to have meaningful, positive, and authentic representation. A person from Mexico writing about the Mexican immigrant experience has a much different perspective then a white women who was born and raised in the United States would have on this same topic, and that difference in perspective matters. In addition, I think authorial representation matters because we don’t want kids to just see themselves in the pages of a book, but to see themselves in the authors of the book. We often hear stories of young kids looking at the characters in books and proclaiming joy that the characters look like them or come from the area that they come from. Imagine how powerful it is to look at that author photo and see that the author looks like them. Some of these kids will be inspired to become not just readers, but authors. And we need to be raising the next generation of authors as well as readers.

But as I mentioned, this conversation is not cut and dry. For a a variety of reasons, an author may not want to share how they identify and that is something that we must respect as well. So my approach is to look at the main characters in the book for one type of representation and the authors for another type of representation. And again, I view this as just additional data to help me make informed collection development choices. So when I go through and do an audit, I never assume an authors identity. I usually use lists that are being shared through professional journals, book blogs, and the authors information itself to help me determine whether or not an author identifies as Own Voices. If they do, then it’s an additional data point for me. If they don’t, I have nothing but respect for that as well.

Over time as I have done diversity audits, I have learned a lot about the authors in my collection. Knowledge is a tool that we can use for good, and in meaningful ways. Knowing whether or not an author is or isn’t Own Voices is just one data set for me to use.

How Do You Know If a Book is Problematic and What Do You Do About It?

Over the years we have come to understand that not all representation is good representation. There are a lot of great conversations happening in our professional iterature and on social media and in our libraries about various books that we have come to understand contain harmful stereotypes and language. We must always give deference to people within the group being represented when they discuss harmful representation. If you are not a member of the group, you don’t get to say if something is harmful or not. As a white woman, I don’t get to say whether or not Little House on the Prairie is harmful representation to Native Americans. My job is to listen to and respect members of Indigenous groups who are telling me that it is. What you do with that information depends on your library system’s policies and administration support. If you are in a position to a weed a title from your collection because of harmful representation, then great do that. Most of us are not. But what we can do is make sure that the books we actively promote, booktalk, share, and prioritize do not contain harmful representation. There are always other books. Moreover, a lot of the books that are often discussed don’t actually need our help with publicity, patrons are already asking for those books. So if promotion is about trying to increase circulation and get patrons reading those gems in our collections that maybe they don’t know about, wouldn’t it behoove us to promote the lesser known gems anyway?

How Do You Do a Collection Diversity Audit?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

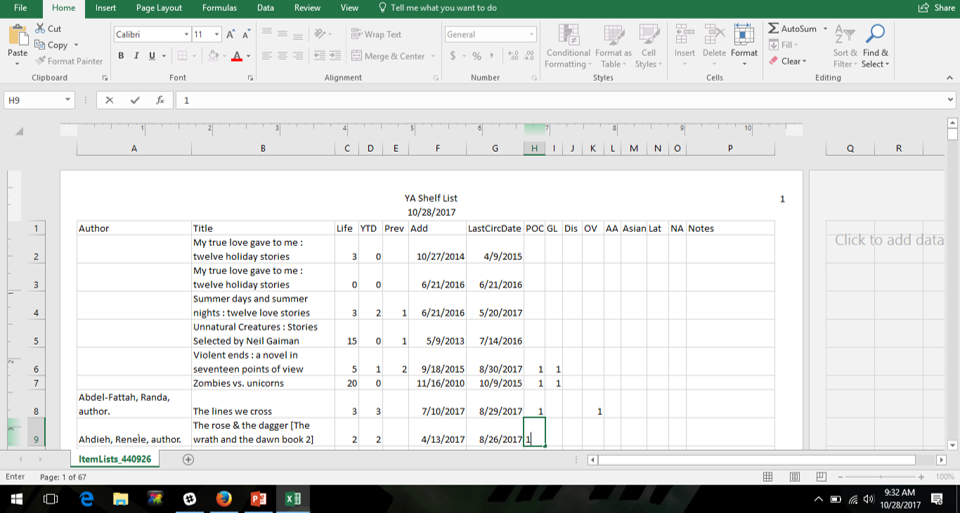

I have a process that works for me and it involves importing shelf lists into Excel. I like to use Excel because you can save your work, add to it, sort and filter the data, etc. I also like Excel because it does the math for me and I can use the built in graph and charts features to create visual data. I am a fan of visual data. I have taught this process for the past 6 years. But I think what’s important is that we understand that collection diversity audits are important and valuable and then each person/system should work to find the process that works best for them. The process is possible, the process is meaningful, but there isn’t just one way to approach the question. And while my way works for me, it may not work best for you. But I want my peers to take away from my discussions about diversity audits is that we CAN be doing this, we SHOULD be doing this, and it is the DATA that we discover and HOW we apply it to our collection development moving forward that matters. I don’t care how you get the data, I just want you to do the work of getting the data and using it to build better, more diverse and inclusive collections.

How Long Does it Take?

I’m not going to lie, an initial collection diversity audit can take a bit of time, depending on the size of your collection. Do it anyway. Taking the deep dive into your collection has nothing but positives. You find gaps and holes you need to fill. You learn more about the titles and authors in your collection so you can make better recommendations, build better displays, and put together better book lists. You will get a better idea of what’s circulating and what’s not and will be challenged to come up with creative ways to share information about what’s in your collections.

The second thing I need you to know is that although the initial audit can be hard and time consuming, once you have that foundation in place it genuinely gets easier and quicker. Also, if you do it correctly, you usually don’t have to start over from scratch because you will have a database of information from your previous audit. If you have the information from an audit in 2015 and repeat an aduit in 2020, you can look at the titles that you have added from 2015 to 2020 instead of doing an entire collection. Or after you do an initial audit you can then just audit book orders as you place them and add the data into your collection audit information folder.

Perfect is the Enemy of the Good

Recently there has been a meme going around my social media TLs about how perfect is the enemy of the good. I understand wanting to create a perfect audit process and wanting to make sure that we have perfect collection data, but I don’t know how we can make that happen realistically given the frequency with which we add and subtract titles to our collections. But I argue that some data – even imperfect data – is better than no data. For most of our libraries we say that our collection goals are to build diverse collections, we assume that we are all doing that, but we don’t have any real way to hold ourselves or our staff accountable. Collection diversity audits can help us do that. And as I’ve mentioned, they are one tool that provides us with some meaningful data. It’s not perfect data, but it is data that we didn’t have before and it helps us be better at our jobs and helps us hold ourselves accountable as we work towards building diverse collections for our patrons. And don’t our patrons deserve the best effort we can give them? Best doesn’t mean perfect, but it does mean better than no effort. At the end of the day, diversity, equity and inclusion work requires intentionality from everyone. This is one of the ways that we can be intentional in our collection development work.

Complete YA Collection Diversity Audit Series

Doing a YA Collection Diversity Audit: Understanding Your Local Community (Part 1)

Doing a YA Collection Diversity Audit: The How To (Part 2)

Doing a YA Collection Diversity Audit: Resources and Sources (Part 3)

Diversity Audit Outline 2017 with Sources

Filed under: Collection Development, Collection Diversity Audits

About Karen Jensen, MLS

Karen Jensen has been a Teen Services Librarian for almost 30 years. She created TLT in 2011 and is the co-editor of The Whole Library Handbook: Teen Services with Heather Booth (ALA Editions, 2014).

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Happy Poem in Your Pocket Day!

This Q&A is Going Exactly As Planned: A Talk with Tao Nyeu About Her Latest Book

Family Style: Memories of an American from Vietnam | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

First, of course it is essential that people from all groups be represented in literature, the arts, and every other field. This is beyond dispute. However, the idea of a librarian promoting the idea of “weeding” books which someone has deemed “problematic” is really chilling. Historical context matters. There is also a difference between descriptive and prescriptive. The mere fact that an author is a member of a particular group does not mean that she will necessarily portray accurately every single aspect of that group’s history or experience. Authors need to do research and editors need to check manuscripts. Does a person living in the 21st century necessarily write “authentically” about members of her own group living one hundred years ago? Do you also realize that the standard you are applying will delete most of the classics of world literature from your collections, depriving library patrons, including teens, from an outstanding range of literary works? Readers don’t identify with characters exclusively when they share the same ethnic, racial, or gender identity. Yes, we should listen very carefully and respectfully when people object to depictions which they consider negative. Some of those books do turn out, by consensus, to be only racist or sexist and without any value at all. But there are many, many areas of nuance which you are just rejecting. Finally, the idea that you need to throw out older books, even avoid talking about them, in order to promote new books is disingenuous. What about inter-library loan? Even if you have to deaccession some books in the interest of space, that does not entitle you to suppress others. This is just censorship by another name. Librarians should be guardians of intellectual freedom.

I do realize that most of the classics would now be considered problematic. I also state pretty clearly that in almost every library weeding those books wouldn’t be supported. What I maintain is that there are often newer and better books that we can and should actively promote because the other books don’t really need our active promotion, they are being assigned, requested, and are well known.

Karen, Thank you for your reply. I sincerely doubt that all of the very worthy new books which you would like to promote are “newer and better” than everything in the past. I would also disagree that older books don’t need to be promoted; sadly, this is not true. If fact, librarians sometimes discard older books not due to ideological reasons, but simply because they are not circulating. I would not assume, for example, that kids and teens are all reading the Little House books; it is even less likely that they read Little Women. I just gave two examples because those are books which now seem inaccessible due to their vocabulary and cultural allusions from far in the past. Even the length of a book is a factor. Educators and librarians should respond to students’ interests, but they also need to realize that kids and teens need guidance. We should not withdraw a huge part of our literary legacy in the narrow interest of promoting newer books. New and old are not mutually exclusive in the world of literature!

I think we are having disagreements about small word choices. For example, when I replied and said newer and better are “often better”, I am referring here specifically to conversations about harmful representation and I use the qualifier often to leave space for an acknowledgment that it is not always the case, just often the case. There is no library that I know of that are withdrawing large portions of our literary legacy; though I do think it is important to acknowledge that due to systemic racism that a lot of voices were left out of our “literary legacy” and part of what we are trying to do is to create a more balanced, inclusive literary legacy for kids today and of the future. And helping young readers find those under represented voices are part of the guidance specifically that I am addressing in answer to this question. If, for example, I have a student asking about books with Native American representation, I don’t think that the Little House books should be our go to choice no matter how popular it has historically been. I would look for and go to books with Native American representation that is written by an Indigenous author whenever possible. I am not, personally, wedded to the idea of the classics as other librarians are, in part probably because I am a public librarian and not a school one. I say let kids read what they want to read and help them find that. In a public library setting I have found that youth will come in and ask for the classics, often because they are assigned either in school or by a parent, but what they choose to read on their own is often newer books, in part because they find the settings, language, and situations more relatable. I have at no time advocated removing large chunks of any library collection, though I do ask us to consider what we promote, to whom, and why. I don’t find new and old to be mutually exclusive, but I do find that the who, what, why and how of them are different for adults compared to kids. And again, I am not speaking as an educator but as a public librarian who serves youth, and there is some difference I have found in that.

First, thank you so much for posting all of these resources. They’ve been a huge help while I do the first ever diversity audit on my j fiction collection.

I’m wondering what you did about anthologies though. For example, I have a book of 36 short stories by all different people and I don’t know if I should count it 36 times for each author and MC or what would be the best way to go about these, since they’re only one book and counting them as more than one book would throw my percentages. I’m a long way from finished (I have almost 8000 titles to go through!) so I’m just largely ignoring them right now.

I personally count anthologies as 1 title because you’re right, it would throw your count off. Also, thanks for reading and for doing an audit! Karen

HI! Thanks for the resources. I am a MLIS student working part-time in a library where I am in charge of 900s nonfiction. Do you have any resources/recommendations for doing a diversity audit for a nonfiction collection rather than children/YA fiction? I’d love to do something like this for my collection.

Thanks!