What if paying library staff and teachers to read IS part of the anti-racist work we could, and should, be doing?

Background, Part 1: No, in fact, we don’t get paid to read

One of the things I most often hear when I tell people that I’m a librarian is this: I wish I got paid to read all day. Fun fact: As a librarian I have never, in fact, gotten paid to read. In fact, most of the libraries that I have worked at have expressly forbidden reading while on the clock and then demanded that library staff be well read because part of our jobs is helping patrons find books and doing good reader’s advisory. Funny how that works.

This dynamic means one of two things. One, you have library staff that don’t read because they would have to do so on their own time, which means that all of the book knowledge they have comes from whatever they read in school or casually on their own time. Spoiler alert, whatever they read in school was most likely predominantly written by a white male author and is part of the traditional cannon, whichever age group they were reading and studying. And two, if you do have well read library staff, that means that they are reading on their own time and the library or school is benefiting from the unpaid labor of their staff. Librarianship and education are two of the professions which benefit a lot from both the unpaid labor of their staff and staff spending their own money on materials to help enhance the program. Libraries and schools are wildly underfunded and many of these professionals end up using their own time and money for ongoing professional development and even basic daily supplies.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Background, Part 2: The Overwhelming Whiteness of Librarianship and Education

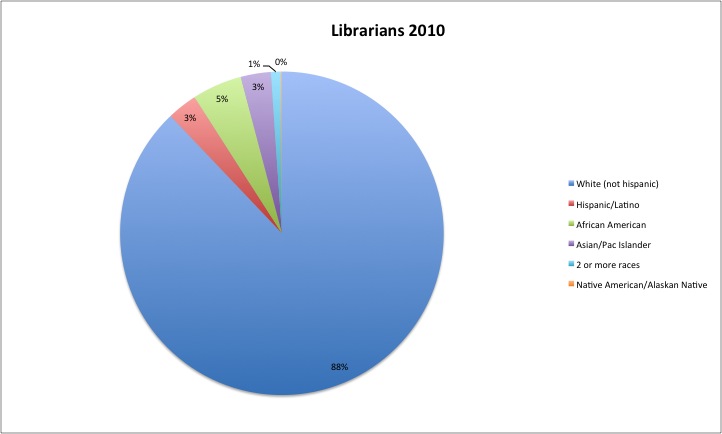

Librarianship is a predominantly white occupation. To be more specific, it is predominately a white female occupation. Upwards of 80% of librarians are just like me, a white woman in her 40s (Source: ALA). This is also true for education; over 80% of teachers in 2016 were white (Source: Department of Education). Someone asked recently on Twitter how old you were before you had a Black teacher and neither I, my husband or my two children have had a Black teacher. I went all the way through graduate school without ever having a Black teacher. And my husband and I went to primary school in Southern California, arguably one of the more diverse states in our country.

There is a lot to unpack and discuss regarding the barriers to entry into these professions and the inequities that make them continue to be so largely predominantly white, and those conversations are happening. They are important conversations and it is very important that every aspect of librarianship and education diversify and become more equitable. I encourage my fellow white librarians to read more on the overwhelming whiteness of librarianship, why it matters, and how we can and should help to deconstruct that.

Background, Part 3: The Canon

Those of us in librarianship and education, the people who are buying, reading, teaching and promoting books, often rely on the books we know and feel most comfortable with. The Canon, as it is often called, is and has historically been written predominantly by white males. There are, of course, exceptions, but those are few and far between. Most of what we learned in our own education was built on a foundation of white texts. Lord of the Flies, Shakespeare, The Great Gatsby, John Steinbeck, to name just a few.

And even if you got your degree in the last 10 years from an accredited college or university and studied youth literature, you still probably read primarily books written by white authors because as the statistics tell us, white authors continue to dominate what’s published (Source: CCBC, Lee and Low). This means that a majority of our reading of foundational texts has centered whiteness. For more on this topic, check out the discussions on Decolonizing our Libraries/Bookshelf and Disrupt Texts. These are both initiatives that ask us all to look at what we’re reading and hold ourselves accountable for reading and teaching more diverse texts. You’ll also want to listen and follow the discussions surrounding #OwnVoices.

The Argument

Library and education staff need to be continually reading to keep themselves updated on newer works and to decenter the white experience which has traditionally been emphasized in education. Because this is a vital part of both of these jobs, libraries and schools should pay staff for time spent reading because it is, in fact, vital professional development.

Right now, libraries and schools everywhere are sharing lists of anti-racist reading. But what good are those lists if our own employees don’t even have the space or the time to do the reading? Yes, we could all choose to do the reading on our own time. And many of us will. But requiring staff to provide us with unpaid labor is an unethical practice. It also means that far too many of our staff aren’t, in fact, doing the work because they can’t, or won’t, for various reasons.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Let me be clear on this: In a profession that demands that people be well read in order to either stock library shelves or do good reader’s advisory or to choose and teach meaningful works of literature to kids and adults, we should always have been paying our staff to read. But in this time where we are talking more and more about the importance of reading and knowing diverse literature and doing anti-racist work, we should be paying our staff to do the work to help us better serve our patrons and better educate our communities. We have always needed to be reading and to be reading diversely, but we should definitely do this in meaningful and intentional ways moving forward if we want to cultivate a better read staff and to better take care of our patrons/students.

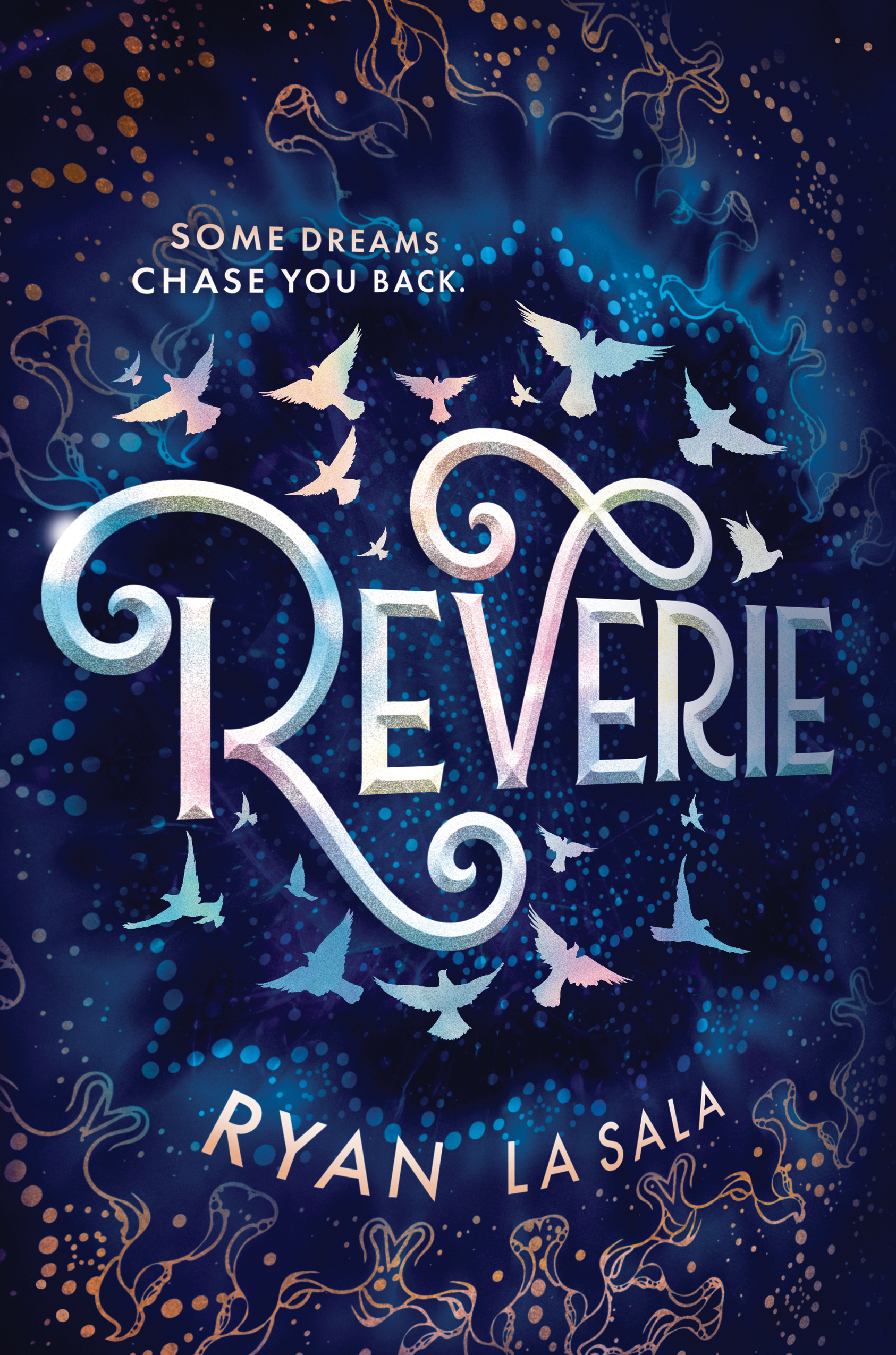

Please note, I’m not just talking about having staff read anti-racist nonfiction, which we should also be paying staff to do. But paying staff to read board books, pictures books, easy readers, middle grade, YA and adult fiction by BIPOC. That’s the work. Knowing our collections is a very important part of the work so that we can select, share, promote, teach and recommend diverse books to our patrons and in our classrooms.

We can and should have arguments about how one would make sure that if we pay staff to read we can make sure they are reading diversely. There are various ways you could implement this. And this is another benefit of paying staff to read, since you are paying staff to read you can, in fact, implement ways to make sure they are reading diversely. This could mean having staff track reading and auditing their reading. Or it could involve assigning various books. It could mean putting staff into accountability groups. What that can and should look like can and should vary, and that’s not the focus of this post. Here, I simply want to say this: paying staff to read new and updated books is part of professional development and if we implement it in meaningful ways it can be an important part of doing just a small fraction of the anti-racist work we should be doing in our professions. It won’t solve all of the issues, but it’s an important part of the work we need to be doing.

We should have always been doing it, so let’s not make any excuses for ourselves or our professions moving forward. Let’s do the work – and pay our staff for their time doing it.

Filed under: Professional Development

About Karen Jensen, MLS

Karen Jensen has been a Teen Services Librarian for almost 30 years. She created TLT in 2011 and is the co-editor of The Whole Library Handbook: Teen Services with Heather Booth (ALA Editions, 2014).

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

In Memorium: The Great Étienne Delessert Passes Away

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

Yes!

And I would wager a pizza that staff who are themselves from marginalized communities are more likely to do this important reading on their personal time. So yet again, it’s the least privileged who are doing more work for less compensation. Fairly compensating this intellectual and emotional work should be an ongoing part of antiracist practice in libraries.

Totally agree.