The Bad Man With the Nice Smile, a guest post by Victoria Lee

Content warning: discussion of sexual assault, rape, child abuse, and gaslighting.

In September 2019, Netflix released a new miniseries, Unbelievable. The show followed the true story of a young girl who claimed a stranger broke into her house at night and raped her. But when she reports what happened to the police, parts of her story don’t seem to match up. As the series unfolds, we become aware of all the ways the system—but also the girl’s friends and family—have become biased against her. She’s a resident in a group home, a former delinquent, a foster child with a history of acting out, who had made accusations of abuse before. Everyone seems to assume that she is lying for attention.

As you might have predicted by now, she wasn’t lying. But by the time her attacker was caught and brought to justice, the damage was done; the girl had already been abandoned by everyone she should have been able to trust, just because she didn’t match the vision of what a “real” victim looked like in their heads.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The idea of real victims is a pervasive and pernicious one. Turn on the news and you’ll hear a litany of all the things that real victims do: they wear the right clothes, they don’t go out at night, they report the crime to the police and they don’t wait to do it, they have never made these kinds of allegations before. We are told these things even though victims cannot control the behavior of their aggressors, even though being in foster care or having mental illness or having been previously victimized all substantially increase your likelihood of experiencing future violence. Even though externalizing behaviors like drug use and acting out are often symptoms of having survived abuse.

As a child, I was sexually abused for four years, from ages twelve to sixteen. The perpetrator—although maybe I should say the molester or the rapist or the abuser, all of which are less sanitized and therefore strike me as more accurate—was a close friend of the family. He was my neighbor, my triathlon coach, a man so enmeshed in our lives that I described him to other people as my uncle because any lesser word seemed inadequate to describe the relationship he had with my family. He was in his early thirties and looked like Orlando Bloom and every single one of my friends who came over to the house commented on how ungodly hot he was.

When I was thirteen, I even wrote a character in one of my stories to look just like Brian. (We will call him Brian, because that is, in fact, his actual name. F you, Brian.) The character was the love interest, and was also the protagonist’s teacher. As you can see, already I knew that my job as victim was to romanticize such things. That was the only way to survive.

Brian was not a man in the bushes, was not unshaven in a stained wifebeater; he had no substance abuse problems that I was aware of; he was just a guy. A tall, athletic, well-educated, charismatic, attractive guy. Kids loved him, and he loved kids. Me, on the other hand…I couldn’t be a victim.

I was not what a victim looked like. I was a problem child. I spent too much time on the internet, and listened to angry music, and skipped class and stole my parents’ credit card and shoplifted and screamed at teachers and once threatened to kill a boy who touched me wrong. I was the girl that other girls weren’t allowed to be friends with. I was the girl they prayed for at night. I was the girl who wore boys’ clothes, all black, and kissed other girls and insisted it wasn’t a phase.

Therefore, I was not believed. Not by my family, not by my therapist. I was believed by the crisis team that was called in to evaluate me when the staff at the psychiatric hospital I was later admitted to following a suicide attempt suspected abuse. But at that point the damage was done—I swore to the crisis team that nothing had happened, their suspicions were unfounded, anything I had to say to keep the past buried. I couldn’t deal with being told, once again, that I wasn’t a victim.

Eventually, other girls came forward about my abuser, and he was charged by the state, and ultimately convicted. But this isn’t the kind of trauma you move past. Not just the trauma of the abuse, but the trauma of being told you’re too villainous to ever be victim.

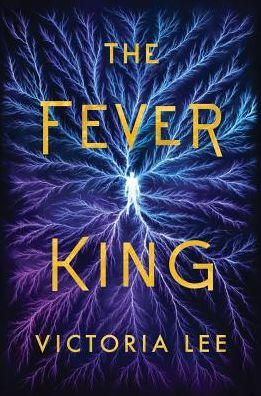

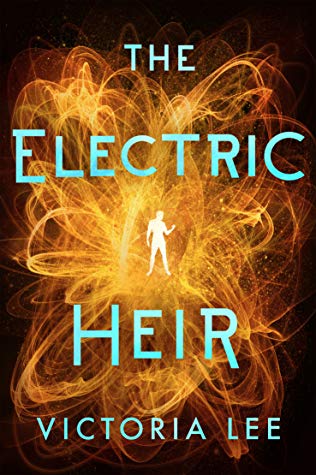

This is why I wrote The Fever King and The Electric Heir. In the series, Dara and Noam both experience abuse in different ways. Dara was physically and sexually abused by a father figure, whereas Noam became enmeshed in an unhealthy, manipulative, exploitative relationship with a much older and much more powerful mentor figure. Both characters are, ultimately, abused by the same man, but their experiences of that abuse are different. The books follow how each character comes to terms with what happened to him, and begins the process of healing. Their abuser, like mine, was charismatic and respected and good-looking—he wasn’t the rapist hiding in the bushes or the drunk frat bro, he was a pillar of the community. When people look for the bad guy, they aren’t looking for Brian. They aren’t looking for Calix Lehrer.

That’s why it was so important to me to write about abusers who don’t fit our vivid stereotype of what an abuser ought to look like—that makes it more difficult to recognize abusers in the real world. And equally so, not all victim/survivors fit the same mold. Some survivors withdraw from the world and become quiet and nervous and fear sex. Other survivors lash out, angry, furious, willing to burn down anything that tries to hurt them again. And still others seem oddly unbothered by what happened to them, numb to the pain or burying it so deep they no longer feel it anymore.

All of these reactions—and others—are okay. The only “right” way to respond to trauma is the way that helps you survive.

I don’t think that good and varied representation of victim/survivors and abusers in literature is a panacea. Abusers are very skilled, after all, at gaslighting their victims (and everyone else). But wide representation of survivors and perpetrators is one step toward chipping away their power and undermining the stories they try to tell about villains and victims and heroes.

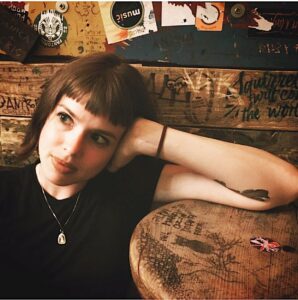

Meet Victoria Lee

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Victoria Lee grew up in Durham, North Carolina, where she spent twelve ascetic years as a vegetarian before discovering that spicy chicken wings are, in fact, a delicacy. She’s been a state finalist competitive pianist, a hitchhiker, a pizza connoisseur, an EMT, an expat in China and Sweden, and a science doctoral student. She’s also a bit of a snob about fancy whiskey. Lee writes early in the morning and then spends the rest of the day trying to impress her border collie puppy and make her experiments work. She currently lives in Pennsylvania with her partner.

www.victorialeewrites.com Facebook: @victorialeewrites, @amazonpublishing Instagram: @sosaidvictoria, @amazonpublishing, Twitter: @sosaidvictoria, @amazonpub

About The Electric Heir by Victoria Lee

In the sequel to The Fever King, Noam Álvaro seeks to end tyranny before he becomes a tyrant himself.

Six months after Noam Álvaro helped overthrow the despotic government of Carolinia, the Atlantians have gained citizenship, and Lehrer is chancellor. But despite Lehrer’s image as a progressive humanitarian leader, Noam has finally remembered the truth that Lehrer forced him to forget—that Lehrer is responsible for the deadly magic infection that ravaged Carolinia.

Now that Noam remembers the full extent of Lehrer’s crimes, he’s determined to use his influence with Lehrer to bring him down for good. If Lehrer realizes Noam has evaded his control—and that Noam is plotting against him—Noam’s dead. So he must keep playing the role of Lehrer’s protégé until he can steal enough vaccine to stop the virus.

Meanwhile Dara Shirazi returns to Carolinia, his magic stripped by the same vaccine that saved his life. But Dara’s attempts to ally himself with Noam prove that their methods for defeating Lehrer are violently misaligned. Dara fears Noam has only gotten himself more deeply entangled in Lehrer’s web. Sooner or later, playing double agent might cost Noam his life.

ISBN-13: 9781542005074

Publisher: Amazon Publishing

Publication date: 03/17/2020

Series: Feverwake Series #2

Ages 14-17

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

K is in Trouble | Review

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT