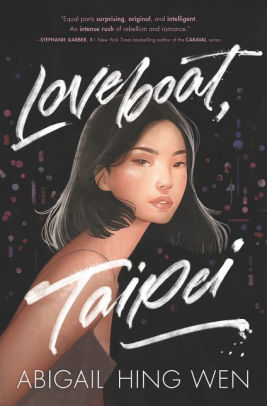

Four Little Words – Changing the Narrative, a guest post by Abigail Hing Wen

As a student rising through elementary and middle school in Ohio, I’d always wanted to join one of the amazing productions put on every year by the high school theater group. A part of me worried that my Asian Americanness would get in the way. After all, there were no Asian Americans in Oklahoma! or Guys and Dolls. Would casting me detract from authenticity? Could the directors overlook my Asian Americanness so that in spite of my face, I could join the chorus?

My freshman year, I auditioned for the fall play. When the cast list posted, I wasn’t on it. But freshman were rarely cast for any roles but the chorus, and with the winter came a special class of one-act plays, directed by seniors. They were smaller and less prestigious; an opportunity for freshman, though still difficult to land.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

During auditions, the seniors sat in the front row of the auditorium while we hopefuls huddled on the floor before them. They challenged us: how far would you go? would you run naked across the stage?

I can’t remember my answer, but I remember the attitude that dominated that room: whatever they threw at us—a crazy dance routine, a passionate stage kiss—we were game.

I auditioned along with dozens of other hopefuls.

When the cast list posted, I pressed forward with the mob, anxiously scanned the list, read deeper and deeper—and there I was!

In a one-act play called “Four Little Words,” I had been cast as the Sixth Actress of seven actresses.

When I arrived for rehearsal, I could scarcely contain my excitement. Two senior guys were directing. There were about a dozen of us actors—I had joined an exclusive little club.

Eagerly, I flipped through the thin blue booklet we were given, searching for my role. It was a story of a director trying to cast for the role of a maid who only had four words in the whole play: “Your taxicab is waiting.”

He proceeded to audition one egotistical actress after another. Each prima donna embellished on the four little words, refusing to stay in character, while he grew more and more despairing, exhausted by these women who wouldn’t shut up.

Meanwhile, the sixth actress—me—sat at the end of the line without speaking. The seventh actress burst onto the scene, large than life.

And then when the director was about to tear out his hair, my character finally spoke.

“Vosh naya. Skoogoo. Urr-urr. Saltzey. Kcki-icki skaya. Woozey.”[1]

The office boy turned to the director and said, “Gee, boss! She can’t talk English!”

The poor exhausted director came to life.

“She’s hired!” he cried. “I never want to hear English again!”

I was suddenly, intensely aware I was the only minority in that auditorium. The words weren’t even a real foreign language. They were a made up language, the kind of talk random people occasionally babbled at me when they passed me on the street.

I had been cast not despite my Asian Americanness, not even for it, but because of the perception of it.

In the weeks that followed, I never breathed a word about the play’s contents to my parents or my friends. I told my parents they didn’t need to attend, though, since I missed the bus for practices, my mom dutifully picked me up late after school every day.

We actresses sat in a row each rehearsal. I sat in silence, my head bowed, as my role called for, until the cue for my four little words. Each time I spoke those lines, I died a little with the shame of it. But I’d been cast. I got a role when so many others didn’t. I’d agreed with all the other hopefuls that I was game for anything. How could I rock the boat now and appear ungrateful?

“Is that Chinese?” the fifth actress asked me one afternoon.

I was born in the United States. English was the only language I spoke at home. I had studied French for two years and that was my second language. When people complemented me on my excellent English skills, it had been a point of soreness, but also irrational pride.

I don’t remember what I answered. But I remember the feeling.

I started leaving rehearsals early. One time, I skipped, making some excuse. The next day, after I recited my lines, the fifth actress said to me, “You know, Bob (not his real name, but the one-act’s real-life director) played your role yesterday and he was hilarious. Why don’t you ham it up more?”

Until I wrote this piece and my critique partner pointed it out, I didn’t recognize that the hamming up of the role was probably a racist caricature, as much as the role itself was. Instead, I felt like a failure. Of course Bob was hilarious. And I couldn’t be. For so many reasons I couldn’t in that role.

A good friend, one of three other Chinese Americans in the grades above me, came to the one-acts. I didn’t know he was in the audience until he came up afterwards and congratulated me with a huge grin.

Not until three years later, when he and I were both students at Harvard, that I confessed how ashamed I’d felt to play it.

“I was actually really mad when I saw the show,” he admitted.

Why had we never talked about it? Why didn’t I have more self-confidence to refuse the role? I doubt it even went on my college application. It was something I endured and buried away. I simply didn’t know better. Those student directors and the supervising theater directors and faculty may not have realized what they were doing, although I think they did in hindsight—I walked in on an argument in which the director was trying to convince the play’s leading man to take his bow with me on his arms and he was refusing. Not wanting to be the cause of a fuss, I quickly offered to take my bow with the other actresses.

As I’ve explored film options for Loveboat, Taipei, I’ve had the opportunity to meet Asian American producers who have struggled to get their work made in the United States or to gain traction in Hollywood. They have been told there are not enough qualified Asian American actors.

“That’s because they don’t have a chance to practice,” one discouraged director told me. “They’re not cast as leads in high school plays or musicals.” And in an already fiercely competitive market, with so few roles for Asian Americans, what actor could go into it with any real hope?

But I am also told there is incredible talent out there. I’m running into it. My hope for a Loveboat, Taipei film someday is that its cast of over 30 Asian American characters will open up opportunities for this talent to come forward and shine on the screen. I want to see new stars discovered, and to see them move into other lead roles in Hollywood in which race doesn’t matter.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

With Crazy Rich Asians, Always Be My Maybe, To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before, The Farewell and Ghost Bride, we are starting to see changes. We still have a ways to go, but I am honored and grateful to be playing a part in this new world.

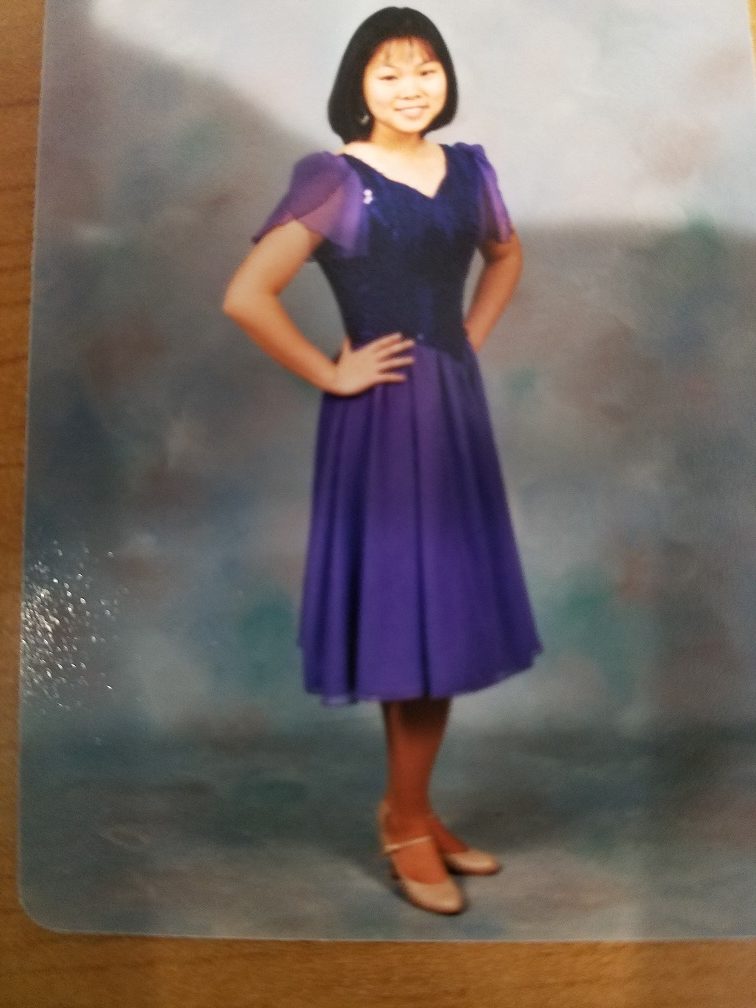

Meet Abigail Hing Wen

Abigail Hing Wen holds a BA from Harvard and a JD from Columbia. She also earned her Master of Fine Arts in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Like Ever, she is obsessed with musicals. When she’s not writing stories or listening to her favorite score, she is busy working in venture capital and artificial intelligence in Silicon Valley, where she lives with her husband and two sons. Loveboat, Taipei is her first novel. Visit AbigailHingWen.com.

About Loveboat, Taipei

Perfect for fans of Jenny Han and Sarah Dessen, and praised as “an intense rush of rebellion and romance” by #1 New York Times bestselling author Stephanie Garber, this romantic and layered Own Voices debut from Abigail Hing Wen is a dazzling, fun-filled romp.

“Our cousins have done this program,” Sophie whispers. “Best kept secret. Zerosupervision.”

And just like that, Ever Wong’s summer takes an unexpected turn. Gone is Chien Tan, the strict educational program in Taiwan that Ever was expecting. In its place, she finds Loveboat: a summer-long free-for-all where hookups abound, adults turn a blind eye, snake-blood sake flows abundantly, and the nightlife runs nonstop.

But not every student is quite what they seem:

Ever is working toward becoming a doctor but nurses a secret passion for dance.

Rick Woo is the Yale-bound child prodigy bane of Ever’s existence whose perfection hides a secret.

Boy-crazy, fashion-obsessed Sophie Ha turns out to have more to her than meets the eye.

And under sexy Xavier Yeh’s shell is buried a shameful truth he’ll never admit.

When these students’ lives collide, it’s guaranteed to be a summer Ever will never forget.

ISBN-13: 9780062957276

Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers

Publication date: 01/07/2020

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT