Writing Myself a New Story, a guest post by Jasmine Warga

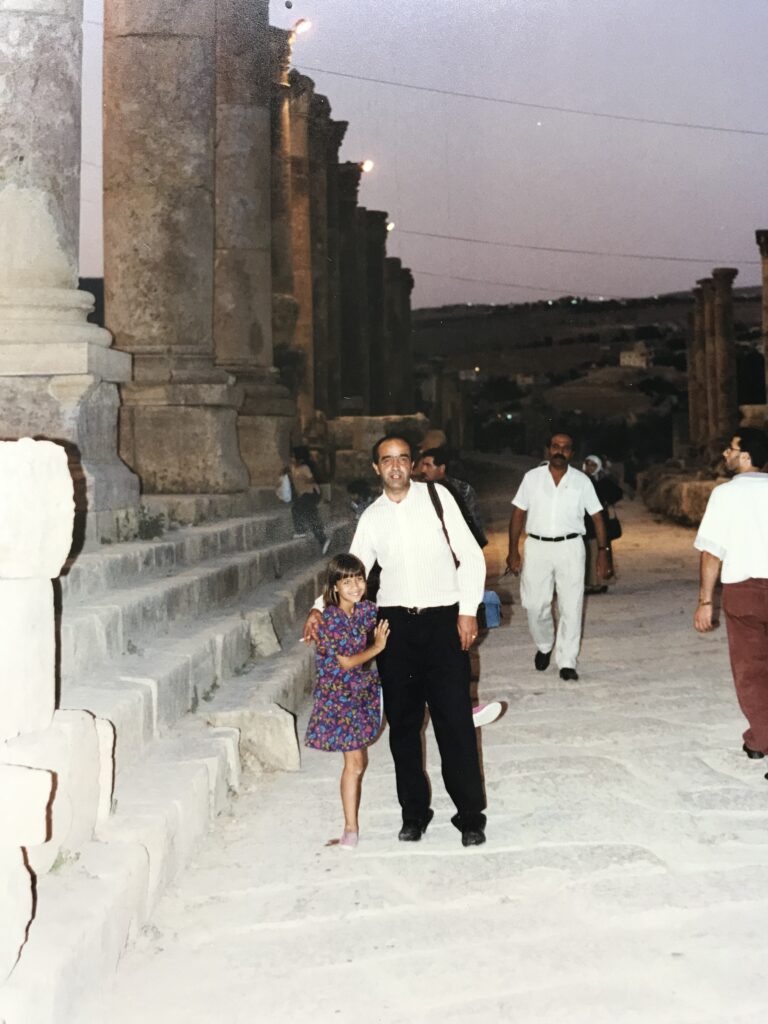

I first met my uncle Abdalla when I was four-years-old. Up until the moment he got off the plane, walked straight toward me and picked me up off the ground with a twirl, whispering in rapid-fire Arabic to me, my uncle had only existed in stories that my father told me.

I didn’t understand most of what my uncle was saying when he greeted me—I was only familiar with a couple of Arabic phrases—but I also felt like I understood every word. That’s how it always was with Abdalla. I understood, and if I didn’t, he made sure that I did.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

My parents had asked him to come to America to take care of me during the birth of my baby brother and the subsequent hectic weeks that would follow. I think their hope was that I’d be too distracted by my new uncle to resent the fact that I was no longer the baby of the family. It worked. My uncle and I spent the weeks leading up to my brother’s birth trading stories. He would tell me about Jordan—my great-aunt with a temper like a snake, my grandmother who believed deeply in otherworldly things, and a whole city made of a rose rock that he would show me when I visited. My uncle is the one who first taught me the true power of storytelling. He rendered Jordan so gorgeously and evocatively that I was desperate to visit.

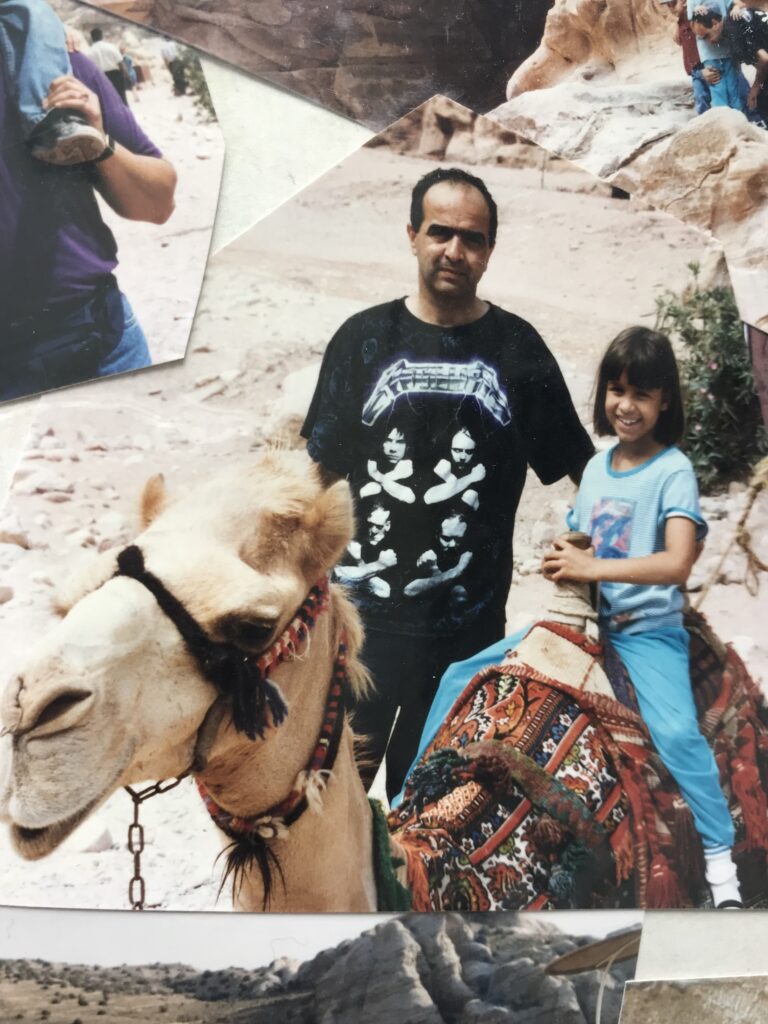

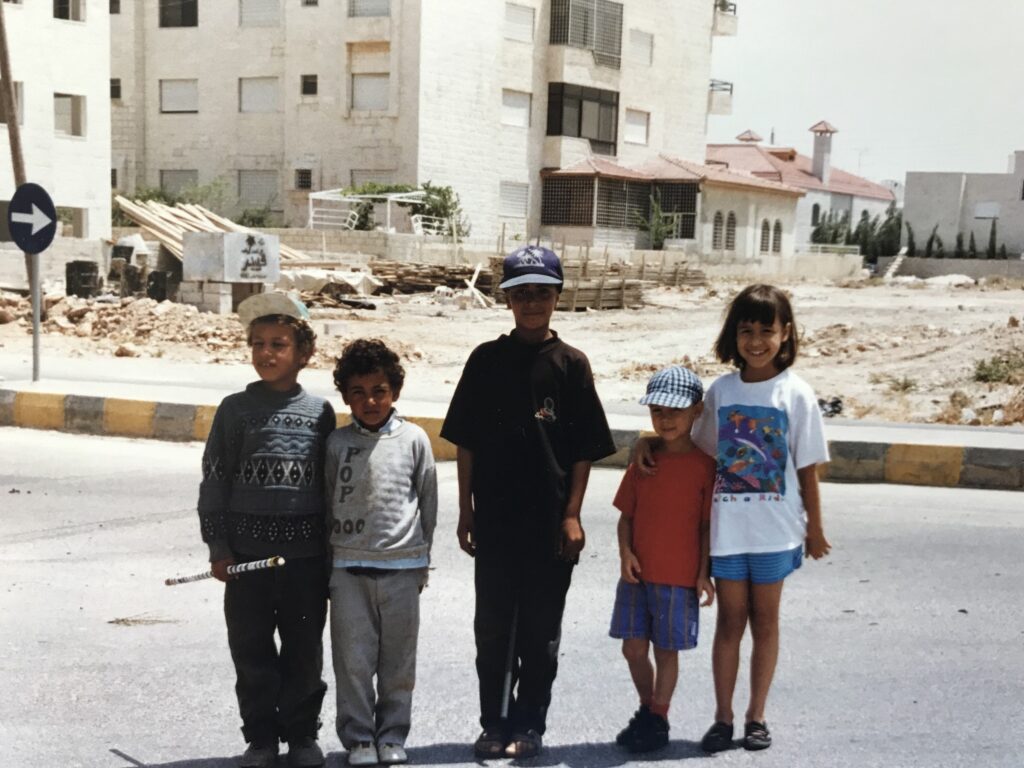

I finally got the chance to visit when I was eight-years-old. My uncle greeted us at the airport, pulling me into a hug, and telling me, “Welcome home” in both Arabic and English. At first, Jordan didn’t feel at all like home. Jordan was people eyeing me with curiosity, confused that my name was Yasmine Nazek, but I didn’t speak smooth and confident Arabic. Jordan was hilly roads that made me slightly nauseous as we drove up and down them. Jordan was open windows at all times, and the sound of the call to prayer at dawn. It was pomegranates that exploded in my mouth. It was big family dinners of mansaf and crowded rooms filled with people I’d never met but who loved me and I loved them. It was playing soccer with local neighborhood children in an empty lot that would soon be filled with luxury condos.

One of the last nights of the trip, I sat with my uncle outside on his patio, and told him through tears that I was going to miss Jordan so much when I went home. That I didn’t want to go home because this was home, could be home. My uncle took my face in his hands, and told me that I could come visit whenever I wanted because, “Jordan belonged to me.”

Jordan belonged to me.

The thing about diaspora kids like me is that it is hard to believe that any place belongs to us.

Not our homes in America where we are othered, sidelined, and marginalized. And not the countries of our ethnic origin because how can you muster the audacity to lay to claim to a country—a culture—that still feels foreign to you, no matter how much you want it to be familiar.

I was always told how lucky I was to have two homes—and I know I am—but it’s also deeply lonely to feel like a stranger in both worlds.

When I got back from that first trip to Jordan, I did a presentation for my third-grade class about it. My dad came in to help. We served the class hummus. This was before everyone in America knew what hummus was. Most of my classmates were excited to try the strange dip in front of them, but you can probably imagine the look on some of their faces—a puckering of the lips, declarations of “weird!” and “ew!”

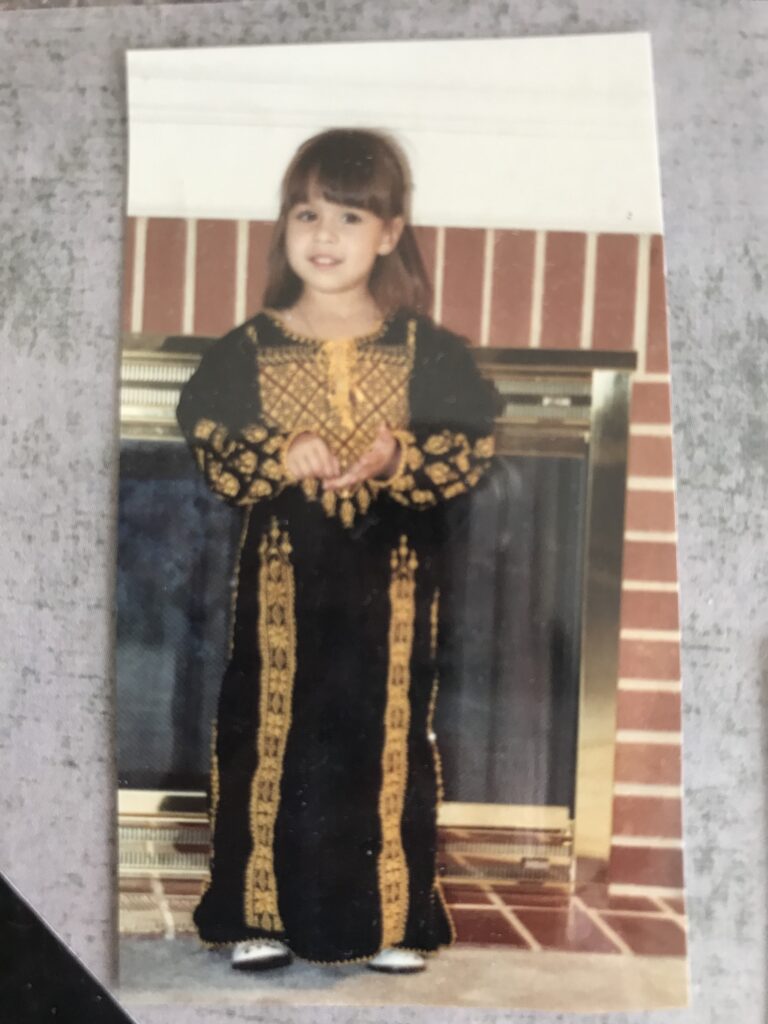

I remember going from a feeling of surging pride—having just shared an incredible photo of Petra—to deep shame. This is one of my first childhood memories of really feeling different from my classmates and wanting not to be. I’m sure I’d had those moments before—I’d must have—but none stand out to me as clearly as this one. Sweating in my hand-embroidered thobe that moments ago I’d been so delighted to wear. Running to the school bathroom to pull it off; and making excuses about why I needed to change that instant.

I was eight years old then. I never talked about Jordan at school again until I was seventeen.

As more and more people begin to read Other Words for Home, I’m being asked if Jude is a stand-in for me when I was twelve. I always pause at this question. The differences are obvious to me. They are almost as wide and daunting as the ocean that Jude crosses in the book. The most glaring of which is, while we are both Arab, Jude is Syrian-born, and I am American-born.

It is not lost on me that the character in the story who I most identify with is the novel’s main antagonist—Jude’s American-born cousin, Sarah. Sarah is hurting on the inside—feeling lost and lonely in a way that she doesn’t even have a vocabulary for—and so she lashes out at others.

I believe so much in positive representation. I used to parrot this idea that our job as writers was to write the world exactly as it is, exactly as we experience it—an academic idea I’d stolen from older white male authors who I’d seen talk about their books. I thought that repeating it would prove that I, too, was hip, educated, and literary. That I deserved my seat at the proverbial table.

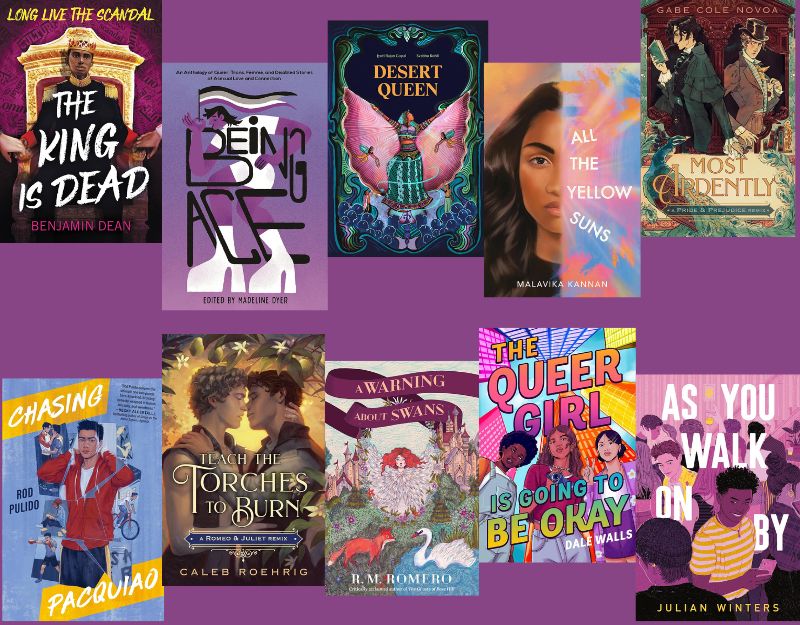

But the older I get, the more I believe that books give birth to the world we live in. Media representation shapes actual perceptions, and so instead of writing sad, lonely brown girls, I decided to write a girl like Jude. A girl who has pride in her family, her culture. A girl who, of course, makes mistakes, but is sure of her heart. Growing up, I never saw a character like Jude. If I encountered a self-assured heroine, she was always white, and beautiful in a way that every media outlet had led me to believe was the only way to be beautiful—fair skin, light hair, a nose completely unlike mine.

Jude does not exist to help Sarah to grow. I want to make that very clear. She has her own story and agency. But one of my very favorite things about the book is the way in which Jude’s confidence in her identity begins to influence the way Sarah sees herself. We can all learn from one another, and the way Sarah learns from Jude, and in turn, the way Jude learns from Sarah, are particularly meaningful to me.

When I was sixteen, and visiting my uncle in Jordan for the summer, I remember whining to him that I didn’t want to be Arab or Muslim anymore. That everyone in the world hated Arabs and Muslims. When I told Abdalla this, memories from my childhood came flooding back to me—desperately wishing to look like my white American girl doll in fourth grade, lying and saying I was Italian instead of Arab in ninth grade, staying silent even though it turned my insides to acid when I heard ignorant things said about Islam. I also thought of the deep shame I felt about not posting a single picture from my visit on Facebook that showed one of my hijab-wearing relatives. Instead posting a series of photographs of the westernized cafes that had recently opened up in Amman.

My uncle didn’t get upset or angry at my declaration. He simply smiled at me in a knowing way. He told me that I only thought that because of the story the American media was telling me. “But Yasmine habibti, you’re a writer, yes? Write another story.”

My uncle Abdalla died before I finished the first draft of Other Words for Home. He never got to read it. But I still like to imagine that somewhere he’s smiling, knowing that I did write myself another story.

Meet Jasmine Warga

Jasmine Warga is the author of the middle grade novel Other Words for Home (Balzer + Bray; May 28, 2019), as well as several teen books: Here We Are Now, and My Heart and Other Black Holes, which has been translated into over twenty languages. She lives and writes in Chicago, IL. You can visit Jasmine online at www.jasminewarga.com.

About Other Words for Home

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

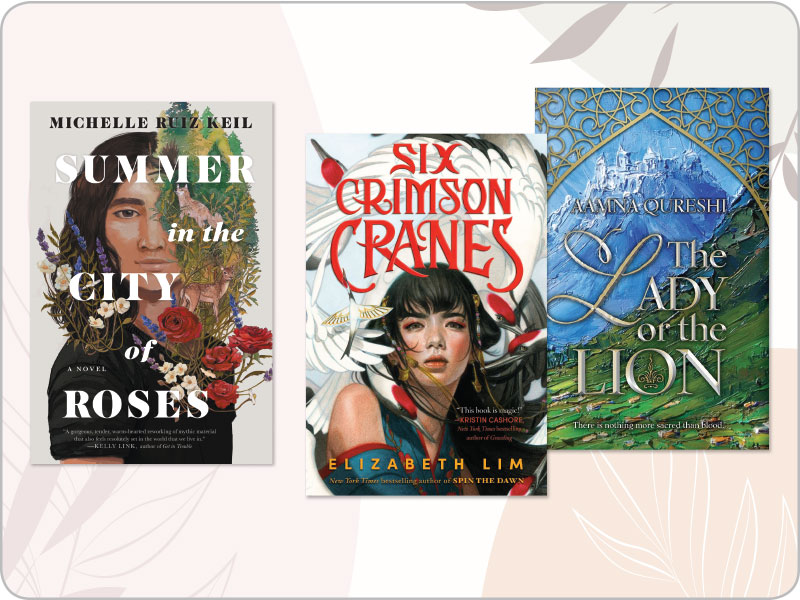

A gorgeously written, hopeful middle grade novel in verse about a young girl who must leave Syria to move to the United States, perfect for fans of Jason Reynolds and Aisha Saeed.

Jude never thought she’d be leaving her beloved older brother and father behind, all the way across the ocean in Syria. But when things in her hometown start becoming volatile, Jude and her mother are sent to live in Cincinnati with relatives.

At first, everything in America seems too fast and too loud. The American movies that Jude has always loved haven’t quite prepared her for starting school in the US—and her new label of “Middle Eastern,” an identity she’s never known before.

But this life also brings unexpected surprises—there are new friends, a whole new family, and a school musical that Jude might just try out for. Maybe America, too, is a place where Jude can be seen as she really is.

This lyrical, life-affirming story is about losing and finding home and, most importantly, finding yourself.

ISBN-13: 9780062747808

Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers

Publication date: 05/28/2019

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Moral Dilemma of THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

K is in Trouble | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

He is smiling dear

Thank you so much for writing this beautiful story about your dear Uncle and your life as a Jordanian and as an American.