How History (and Librarians) Inspire Freedom of the Press, a guest post by Mary Cronk Farrell

When I got my first real job as a broadcast journalist at age 21, I believed my work would contribute to the common good. I believed the stories I reported, first as a radio journalist and later in television news, would help people understand events in our local community more clearly, feel more empathy and maybe open their minds or change their hearts.

When I got my first real job as a broadcast journalist at age 21, I believed my work would contribute to the common good. I believed the stories I reported, first as a radio journalist and later in television news, would help people understand events in our local community more clearly, feel more empathy and maybe open their minds or change their hearts.

Was I too idealistic? Was believing that the news media played a crucial role, not just in preserving democracy, but also as a force for good in our lives nothing but a fanciful notion of a naïve do-gooder?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

It certainly seems so today.

But in researching the stories of black women who risked their lives to serve their county in a segregated army during World War II, I discovered evidence of how a free press pushed our nation to progress toward equality, how newspaper stories about injustice inspired people to empathy, and how the press rallied citizens to demand fairness.

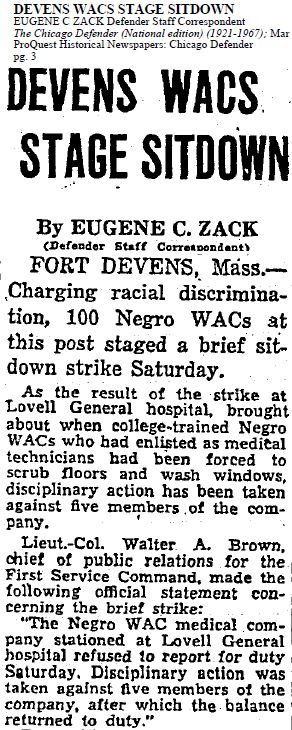

In the spring of 1945, black members of the Women’s Army Corps stationed at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, had withstood all they could stand. Day after day they donned blue work uniforms and reported to Lowell Army hospital to wash dishes and scrub floors. White WACs at the same hospital wore white uniforms for jobs as lab technicians, nurse’s aides and assisting wounded soldiers write letters home.

Throughout World War II, complaints arose, and inspections verified that black WACs were too often assigned to menial jobs not prescribed for WACs. One inspection at Fort Breckinridge, Kentucky, found thirty black WACs working in the laundry, fifteen assigned to service jobs, including dishwashing at the base club, and five “well-educated negro women…administration school graduates…employed sweeping warehouse floors.”* At Fort Knox, Kentucky, black WACs worked in the kitchen, a white officer saying, “Most of these girls are much better off now than they were in civilian life.”*

At Fort Devens, the black women tried to work through the system, sending their complaints of discrimination up the chain of command to no avail. Alice E. Young, 23, had finished one year of nursing school while working as a student nurse in a Washington, D.C. hospital. She’d joined the army due to promises she’d be trained as a nurses’ aide and worked at Lovell awaiting a space in the training program.

But one day the commander of the hospital Colonel Walter M. Crandall toured her ward and saw Alice taking a white soldier’s temperature. “No colored WACs,” he announced, would take temperatures in his hospital. “They are here to scrub and wash floors, wash dishes and do all the dirty work.”**

Alice was demoted to hospital orderly, her hopes of going to med tech school dashed. She cleaned the hospital hallways and kitchen, washed dishes, cooked and served food and took out the garbage. Sixty percent of the black WACs at Lovell had similar duties.

They decided to strike. According to the New York Times, 96 black WACs initially refused orders to go to work due to discriminatory assignments. After several days, most eventually went back to work under threat of court martial for insubordination, a death penalty offense in wartime.

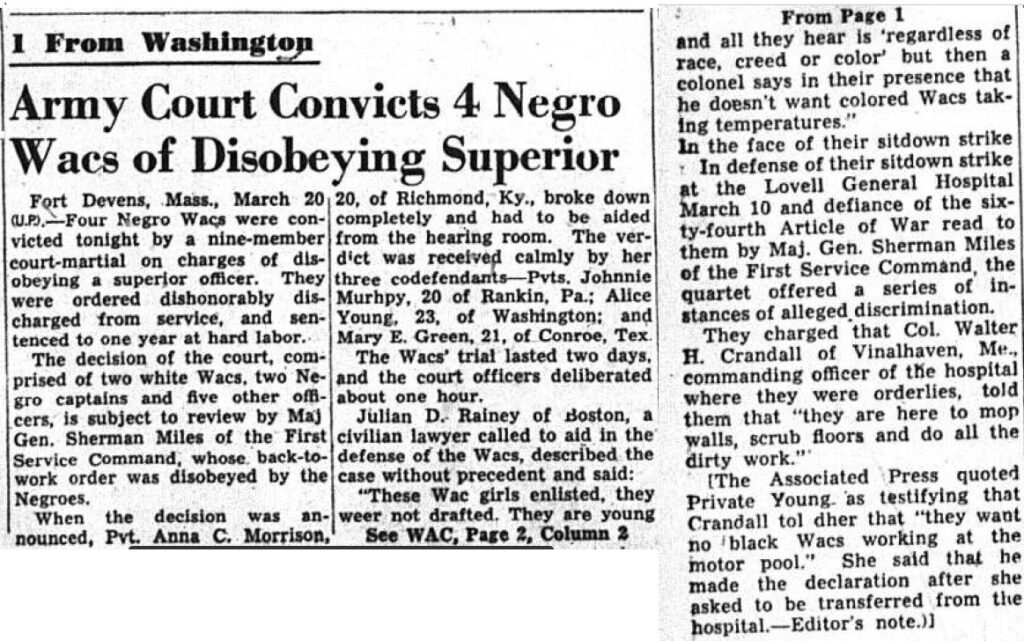

But Alice and three others who walked away from their posts at the hospital did not return and were court martialed. “These women made this gesture of protest in hope that someday their descendants might enjoy fully the rights and liberties promised to Americans,”** their attorney said.

Major news sources like the New York Times and Time Magazine covered the strike and the women’s trial, as well as small town newspapers like the Daily Sun in Lewiston, Maine, and African American newspapers across the country. When the army court convicted the four women and sentenced them to one year of hard labor with no pay and dishonorable discharge, the story received wide coverage.

Many Americans both white and black read about the unfairness the striking women had faced. They protested the harsh penalty by writing letters to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Secretary of War, Congress and editors of newspapers. Many called for punishment of Colonial Crandall, rather than the women.

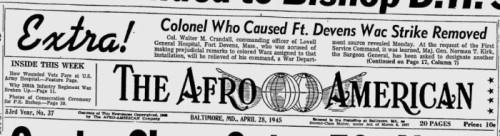

The news stories and subsequent uproar by citizens made a difference. The War Department found a way to reverse the verdict on a technicality and reinstate Alice and the others to active duty. The Army did not investigate Colonel Crandall’s behavior, but he was relieved of his hospital command and pressured to retire. In addition, the army changed policies at Lovell Hospital prohibiting black WACs from being assigned to menial jobs not done by white WACs.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The pervasiveness of our news media today allows us to be even better informed than Americans during WWII, but it requires diligence and critical thinking due to the massive amounts of information at our fingertips, and the phenomenon of “fake news.” Reporters Without Borders, an organization that tracks freedom of information, ranks the United States 45th out of 180 countries on the World Press Freedom Index. We fall below a host of European countries and others around the world including Ghana, South Korea, Uruguay and South Africa.

With the news media’s ever-increasing focus on the sensational and the obvious partisanship of news outlets, I’ve become more jaded and I don’t regret I’ve left the business. But librarians inspire me to keep faith with my ideals. They’re on the front lines championing freedom of information and teaching students critical skills to assess the news they see. They inspire us all to work within our own spheres of influence to defend our freedom of the press which is critical to democracy and a powerful force for truth and justice.

* When the Nation was in Need: Blacks in the Women’s Army Corps during World War II, by Martha S. Putney (Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2001)

**United States V. Morrison, Anna G, A., Green, Mary, E., Young Alice E., Murphy, Johnnie, A. (Proceedings of a General Court-Martial, Fort Devens, M.A., March 19, 1945)

Meet Mary Cronk Farrell

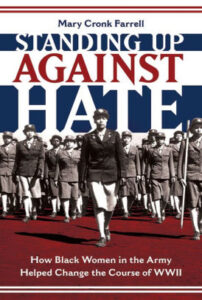

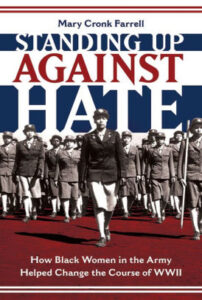

Mary Cronk Farrell, author of critically acclaimed and award-winning Pure Grit: How American World War II Nurses Survived Battle and Prison Camp in the Pacific, now releases the incredible story of how black women in the army helped change the course of World War II: Standing Up Against Hate: How Black Women in the Army Helped Change the Course of WWII (Abrams, January 2019).

Mary Cronk Farrell, author of critically acclaimed and award-winning Pure Grit: How American World War II Nurses Survived Battle and Prison Camp in the Pacific, now releases the incredible story of how black women in the army helped change the course of World War II: Standing Up Against Hate: How Black Women in the Army Helped Change the Course of WWII (Abrams, January 2019).

Connect with Mary online:

Website: www.MaryCronkFarrell.com

Blog: http://www.marycronkfarrell.net/blog

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Author-Mary-Cronk-Farrell-180125525368386/

Twitter: @MaryCronkFarrel

Instagram: MaryCronkFarrell

About Standing Up Against Hate: How Black Women in the Army Helped Change the Course of WWII

Standing Up Against Hate tells the stories of the African American women who enlisted in the newly formed Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) in World War II. They quickly discovered that they faced as many obstacles in the armed forces as they did in everyday life. However, they refused to back down. They interrupted careers and left family, friends, and loved ones to venture into unknown and sometimes dangerous territory. They survived racial prejudice and discrimination with dignity, succeeded in jobs women had never worked before, and made crucial contributions to the military war effort. The book centers around Charity Adams, who commanded the only black WAAC battalion sent overseas and became the highest ranking African American woman in the military by the end of the war. Along with Adams’s story are those of other black women who played a crucial role in integrating the armed forces. Their tales are both inspiring and heart-wrenching. The book includes a timeline, bibliography, and index.

Standing Up Against Hate tells the stories of the African American women who enlisted in the newly formed Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) in World War II. They quickly discovered that they faced as many obstacles in the armed forces as they did in everyday life. However, they refused to back down. They interrupted careers and left family, friends, and loved ones to venture into unknown and sometimes dangerous territory. They survived racial prejudice and discrimination with dignity, succeeded in jobs women had never worked before, and made crucial contributions to the military war effort. The book centers around Charity Adams, who commanded the only black WAAC battalion sent overseas and became the highest ranking African American woman in the military by the end of the war. Along with Adams’s story are those of other black women who played a crucial role in integrating the armed forces. Their tales are both inspiring and heart-wrenching. The book includes a timeline, bibliography, and index.

(ISBN-13: 9781419731600 Publisher: ABRAMS Publication date: 01/08/2019)

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

In Memorium: The Great Étienne Delessert Passes Away

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

Thanks so much!