How Much YA Gets Published Each Year? Discussing YA Collection Development Challenges

This year has been a deep dive into collection development for me. Actually, the last two years have been. Granted, collection development is always a part of the job and it is arguably my favorite part of the job, but these past 2 years I have been deeply involved in analysis and budgets and things like diversity audits. My goal is to put together an in depth YA collection analysis and plan that can help me draw some well founded and supported action items to develop a more comprehensive collection development plan. I want to develop an inclusive YA collection that meets both the supply and demand of YA literature and has high circulation because high circulation means teens are reading. I want goals, facts and figures, and solid statistics that I can take to the table every time I’m discussing YA services with, well, anyone.

As someone who has been doing YA collection development for a solid 25 years now, I have noticed the explosion in YA literature. The number of titles being published has increased, as much as 400% according to some sources. And if you ever visit bookstores like Barnes and Noble, which I do monthly as a part of my own personal collection development, you can’t help but notice that the amount of floor and shelf space dedicated to YA lit has increased there as well. That has not always been true for public libraries. Public libraries have a lot of great qualities, I’m obviously a fan and an advocate, but they also can be slow to adapt and change. Yes, yes, #notalllibraries, but if we’re going to be realistic we have to admit that public libraries on the whole tend to be more reactive than proactive.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Part of the problem is, of course, that although YA publishing has boomed, public library budgets have not. In fact, a lot of budgets have been cut in the past ten years, just as YA publishing was experiencing this boom. In addition, without building new buildings or renovating existing ones, it can often be hard to find additional space for existing or new collections. A lot of libraries have very real space issues and find themselves landlocked. There is no room for much needed growth at a time when more and more formats are being introduced into the market and librarians are being asked to do more with less. The space and budget challenges facing public libraries are very real.

So the question is, what does an ideal YA collection look like? How much floor space does it need? How much shelf space? What is a realistic budget? To answer this question we must look not only at circulation statistics, or demand, but at the supply side. How many YA books are being published each year and how does this influence that amount of floor space and monies that we dedicate to these collections? This question is harder to answer than it looks, in part because I don’t have access to the right data. But it didn’t stop me from trying to figure out a basic beginning reference point.

A pretty regular source of new YA release lists can be found at Goodreads. Here, you can find a monthly list of new YA titles compiled by the Goodreads librarians. This is by no means an authoritative list, because it doesn’t include things like graphic novels, manga, hi/lo readers like Orca published books, etc. These lists focus mainly on big name authors, debut authors, traditionally published authors and the participation of the public. A quick look at the Goodreads list looks like this:

- January – 50 titles

- February – 57

- March – 64

- April – 46

- May – 71

- June – 47

- July – 40

- August – 38

- September – 57

- October – 55

November and December don’t seem to be available yet oddly, but if we go by an average let’s say there are 50 YA books being published each month. This would bring the total number of YA books published and recorded on Goodreads to 625. And remember, this list is not all inclusive or exhaustive, it’s just a beginning point of reference.

Over at Book Birds blog, you can find another list of 2018 YA releases. This one states that there are “over 500 titles” on the list. That’s not a very specific number, and I didn’t go through each monthly list to count and come up with a more specific number. It’s a good resource, however.

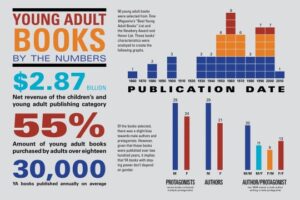

You can also find good lists of new YA releases at TeenReads.com and at YA Books Central. Book Riot frequently publishes lists that cover a 3 months period, breaking the year into quarters, that contain around 150 titles on each list, which would be around 600 titles as well. And of course we use our professional journals and additional sources like Baker and Taylor Growing Minds. An infographic published by The Blooming Twig indicates that an average of 30,000 YA books are published each year, which is a much bigger number than you see in the several sources listed above.

This infographic from New York Books magazine shows the increase in the total of YA publishing through 2012 and indicates that in 2012, 10, 276 YA titles were published. I believe that YA publishing has grown even more since 2012. So in the most basic sense, it seems safe for public libraries to begin at the starting point that at a minimum, anywhere from 1,000 to 10,000 YA titles are being published and marketed to teen readers. Libraries can’t and shouldn’t purchase every title, and not every title deserves to be purchased, which is where selection comes into play, but it’s important that we have a realistic starting point when considering what amount of space and budgets we want to devote to our YA/Teen literature collections.

If we go with the most basic source, Goodreads (and please don’t go with the most basic source when doing collection development), libraries are looking at having to add an average of 52 titles per month, if they bought everything listed on Goodreads. And remember, not everything is listed on Goodreads and not everything listed on Goodreads is worth purchasing for each specific library. And again, it’s worth reminding us all, that this bare minimum purchase doesn’t include things like hi/lo readers, Christian fiction, a lot of series fiction, graphic novels, manga, midlist, re-issues or replacement titles.

Most libraries also use vendors to purchase their books, so they get a pretty decent discount, sometimes as much as 40% off. On average, I have found over the years that I can expect to pay an average of $10.00 per YA book. This means that working with the Goodreads list alone, you would need to have $6,250 in your annual budget to purchase all the popular YA titles listed on Goodreads alone. That’s one copy for one branch to get all 625 titles listed on Goodreads. That’s obviously not how book budgets work, but I think having an idea of what that starting figure might be helps us to develop budgets moving forward. It’s a fact to keep in mind and use in combination with all of the other facts to help us in the process of collection development.

So as a very basic starting point, if a school or public library serving teens was to buy 1 copy each of every YA title listed on most major resources that teens use to help them determine their reading at an average price of $10.00 a book, they would need to have a basic budget of $6,250 to buy around 625 books. At an average of $17.99 retail price, teens would need $11,243.75 to purchase these same titles on their own at retail prices.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I know of school and public librarians who are tasked with building YA collections, including graphic novels and manga, nonfiction and more, with a budget of only $3,000. Collection development is a challenging process in the best of times, but in conditions like these, it can be incredibly hard.

I began this journey by just wanting to find out some basic YA publishing figures to help me get an idea of how many YA titles were being published each year to help me better understand what size a YA collection and budget should be if we weighed supply in with demand. The numbers that can easily and publicly be found (I believe there are industry statistics that others have paid access to that I don’t), indicate that on the whole, most school and public libraries are in fact greatly underfunded and under-spaced when it comes to developing YA collections in relation to the amount of YA titles being published, and this accounts for the fact that we can’t and shouldn’t be just willy nilly buying every title published. I also acknowledge that this is not universally true, there are many libraries that have bigger YA spaces and budgets, but on average I would anecdotally posit that even with the growth of YA services and collections in our school and public libraries, we are still under-serving our patrons in terms of budgets and dedicated floor/shelf space.

I also want to point out that another very real challenge to YA librarians is that teens are no longer exclusively reading traditional published YA books. In addition to a very real and vast transition to digital media, digitally published titles, and a deeper investment in time into social media, teens are also reading a wider variety of self-published titles and fanfiction. Internet sites like Wattpad are changing the ways that teens read and where they get their books. So as challenging as YA collection development is for YA librarians, it’s interesting to note that an additional challenge is that teens want and are reading titles that they don’t need libraries or YA librarians to provide access to. Now, teens have more choices then ever about reading, there are more titles to choose from and more nontraditional ways to gain access to them. The challenges are real for YA librarians who are serving a new generation of digital natives who have far more choices than previous generations.

It’s also an interesting corollary statistic to note that adolescents, or teens, make up around 13.2% of the United States population and ask ourselves if we are dedicating 13.2% of our library resources to this population. Again, this isn’t the only statistic we should be use when determining how to allocate our resources, but it is a statistic we need to keep in mind when considering how best we can help to meet the very real and unique needs of our teens. And it’s not just our teen patrons who are reading YA literature, so developing good YA collections isn’t just about serving our teen patrons, though I hope that when we are engaged in YA services they are always our primary concern no matter who else may be reading YA literature. Teens deserve dedicated services by passionate library staff who are knowledgeable about and invested in their success.

Edited on August 27, 2018 to add this note: As of today, there are already 577 YA titles listed on Goodreads as being published in 2019. Source: https://www.goodreads.com/list/show/88845.YA_Novels_of_2019

Filed under: Collection Development

About Karen Jensen, MLS

Karen Jensen has been a Teen Services Librarian for almost 30 years. She created TLT in 2011 and is the co-editor of The Whole Library Handbook: Teen Services with Heather Booth (ALA Editions, 2014).

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Happy Poem in Your Pocket Day!

This Q&A is Going Exactly As Planned: A Talk with Tao Nyeu About Her Latest Book

More Geronimo Stilton Graphic Novels Coming from Papercutz | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

I break down my collection and budget numbers each year here http://jeanlittlelibrary.blogspot.com/p/library-data-projects-and-reflections.html

Right now I have about 20,000 a year – this includes the whole youth services dept (except AV) so picture books, juvenile fiction and nonfiction, and ya (fiction, graphics, nonfiction, etc.). YA fiction usually gets about 200-300 a month, so about enough for 10-15 books. It’s hard to justify giving YA fiction a bigger chunk of the budget when average monthly circulation is around 400. And we couldn’t fit that many books on the shelves anyways! It’s always a conundrum – do I give more money to a low-circ’ing area in hopes of beefing it up? Or do I keep the budget analogous to the circulation we have?