When Books Are The Things That Save You, a guest post by Cindy Baldwin

When I was thirteen, my parents drove me to the University of North Carolina pediatric hospital and checked me in. I had a PICC line—a peripherally inserted central catheter—put in my left arm and a host of super-strength antibiotics pumped through it. We didn’t know when I’d be coming home. And, hardest of all for a young teenager who hated sleepovers and was preternaturally anxious, my parents—busy with one-year-old baby triplets at home—could only visit me during the day.

The long lonely evenings, the endless nights filled with beeping machines and blood pressure cuffs, were mine to navigate on my own.

It wasn’t the first time I was hospitalized. I’d been in and out of the hospital for my first two years of life, nearly dying as an infant until I was finally diagnosed with cystic fibrosis (CF), a life-shortening genetic disease that affects the lungs, pancreas, and other organs. Those stays, though, existed only in the haziest parts of my memory. More recently, I’d been inpatient two years before, when I was eleven—but that stay had ended up being a fluke, less than forty-eight hours long.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

This, now, was going to be my first real experience with what CF patients call “a clean-out”: a two- to four-week course of intravenous antibiotics to help calm the pneumonia-like lung infections that are CF’s most persistent and intractable symptom. My doctors assured me that after a few days in the hospital I could complete the IVs at home, but they didn’t know how long that would take.

I had never in my life felt as alone as I did that first night in the hospital—like my parents, my friends, my whole life, was in another universe; like none of the people I knew or loved could possibly understand what I was experiencing. The hospital bed creaked and groaned every time I shifted. After I’d turned the lights out to try to sleep, I discovered that no matter what I did the room was twilight-bright. No matter what I did, I couldn’t seem to quiet my racing heart, the anxious blood that pounded through my veins.

I don’t remember, anymore, exactly how long that stay lasted—less than a week. What I do remember, clear as sunlight almost twenty years later, is the person who made my stay bearable: a young medical student named Neeta. Every evening, after she finished her rounds, she’d come sit by my bed and talk books. Like me, she was an avid reader; like me, she loved Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain chronicles and Madeleine L’Engle. She asked me about the books I was reading during that stay (Joan Aiken’s odd and fantastical Wolves of Willhoughby Chase series). She told me about some of her own favorites—even wrote me a list of recommendations on a notepad.

In that whole big, lonely, terrifying hospital, she was the person who made me feel human, like I’d been seen for something more than my disease, something more than the catheter in my arm and the knowledge that these hospital admissions would loom large in my future.

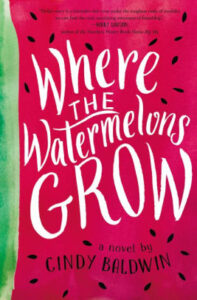

In my debut novel, Where the Watermelons Grow, my protagonist, Della, also feels isolated and afraid, certain that none of her friends in small-town Maryville, North Carolina, can understand what she’s dealing with as her mother’s schizophrenia worsens. Into Della’s loneliness comes newly-transplanted Miss Lorena, who’s moved to Maryville after being widowed. The first time Della meets Miss Lorena, it’s because Miss Lorena’s son is setting up a Little Free Library-esque book box to serve the town of Maryville, which doesn’t have libraries or bookstores of its own. Miss Lorena gives Della a book of Emily Dickinson’s poems, which ultimately becomes one of the things that helps Della find the strength to accept her life, her family, and her mama for just what they are, recognizing that they can still have value even if they look “different.”

In my debut novel, Where the Watermelons Grow, my protagonist, Della, also feels isolated and afraid, certain that none of her friends in small-town Maryville, North Carolina, can understand what she’s dealing with as her mother’s schizophrenia worsens. Into Della’s loneliness comes newly-transplanted Miss Lorena, who’s moved to Maryville after being widowed. The first time Della meets Miss Lorena, it’s because Miss Lorena’s son is setting up a Little Free Library-esque book box to serve the town of Maryville, which doesn’t have libraries or bookstores of its own. Miss Lorena gives Della a book of Emily Dickinson’s poems, which ultimately becomes one of the things that helps Della find the strength to accept her life, her family, and her mama for just what they are, recognizing that they can still have value even if they look “different.”

As a children’s writer, I spend a lot of time thinking about children like Della, children like I was—kids who feel as though their experiences are so different, so overwhelming, that it creates a membrane of isolation between them and their peers. Kids who, so often, find solace and understanding both in books and in strong, compassionate mentors. These are the children for whom books, authors, librarians, and teachers can have an especially profound impact, showing them that they are not alone in their fear, their hardship, their loneliness.

In the past twenty years, like most cystic fibrosis patients, hospitalizations have become a frequent part of my routine; for part of college, it was normal for me to spend about eight weeks a year inpatient. These days, as a busy thirty-something and a mom to a young daughter, the idea of a week in the hospital even sounds like a relief some days. But through almost two decades, the experience of bonding with Neeta over reading during that difficult first hospital stay has stayed with me, a testament to the power of books and friendship to change the heart of a scared thirteen-year-old who could think of few things more terrifying than a night all alone in the hospital.

Meet Cindy Baldwin

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Cindy Baldwin is a fiction writer, essayist, poet, and author of Where the Watermelons Grow (HarperCollins Children’s), her debut middle grade novel. She grew up in North Carolina and still misses the sweet watermelons and warm accents on a daily basis. As a middle schooler, she kept a book under her bathroom sink to read over and over while fixing her hair or brushing her teeth, and she dreams of writing the kind of books readers can’t bear to be without. She lives in Portland, Oregon, with her husband and daughter, surrounded by tall trees and wild blackberries. Learn more about Cindy at www.cindybaldwinbooks.com.

Cindy Baldwin is a fiction writer, essayist, poet, and author of Where the Watermelons Grow (HarperCollins Children’s), her debut middle grade novel. She grew up in North Carolina and still misses the sweet watermelons and warm accents on a daily basis. As a middle schooler, she kept a book under her bathroom sink to read over and over while fixing her hair or brushing her teeth, and she dreams of writing the kind of books readers can’t bear to be without. She lives in Portland, Oregon, with her husband and daughter, surrounded by tall trees and wild blackberries. Learn more about Cindy at www.cindybaldwinbooks.com.

About Where the Watermelons Grow (out today, July 3, 2018)

Fans of The Thing About Jellyfish and A Snicker of Magic will be swept away by Cindy Baldwin’s debut middle grade about a girl coming to terms with her mother’s mental illness.

When twelve-year-old Della Kelly finds her mother furiously digging black seeds from a watermelon in the middle of the night and talking to people who aren’t there, Della worries that it’s happening again—that the sickness that put her mama in the hospital four years ago is back. That her mama is going to be hospitalized for months like she was last time.

With her daddy struggling to save the farm and her mama in denial about what’s happening, it’s up to Della to heal her mama for good. And she knows just how she’ll do it: with a jar of the Bee Lady’s magic honey, which has mended the wounds and woes of Maryville, North Carolina, for generations.

But when the Bee Lady says that the solution might have less to do with fixing Mama’s brain and more to do with healing her own heart, Della must learn that love means accepting her mama just as she is.

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Happy Poem in Your Pocket Day!

This Q&A is Going Exactly As Planned: A Talk with Tao Nyeu About Her Latest Book

Family Style: Memories of an American from Vietnam | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT