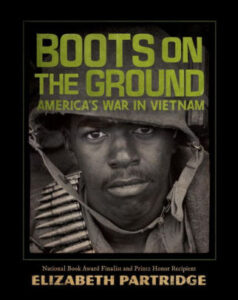

Good Morning, USA, a guest post by Elizabeth Partridge

I’m the last person in the world anyone would expect to write a book about the Vietnam war.

During the late sixties, in high school and college, I was an ardent protestor against the war. The longer it lasted, the more photos and television coverage we saw, the more I despaired at the destruction, suffering, and loss of life of both Americans and Vietnamese.

Like many others, I watched in disbelief as our presidents committed more troops, ordered more bombing raids, dropped more napalm on soldiers and civilians alike. And why didn’t Congress stop the president and his advisors? Between the civil rights struggle and the war, our country was ripped in two.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

With a profound loss of faith in our executive and legislative branches, we headed for the streets, hoping our sheer numbers would create a change in policies. During the same years, anger in African American communities spilled over into violent protests. The government reacted to us with tear gas and guns, turning against its own citizens.

With a profound loss of faith in our executive and legislative branches, we headed for the streets, hoping our sheer numbers would create a change in policies. During the same years, anger in African American communities spilled over into violent protests. The government reacted to us with tear gas and guns, turning against its own citizens.

Now, just over fifty years since President Johnson first ordered “boots on the ground” in Vietnam, we’re facing another crisis of confidence in our government. Young people are protesting once again: impassioned, ardent, and articulate.

In the Vietnam era, protests were widespread, and veterans came home, unwelcomed, even vilified. They kept their heads down, and tried to get on with their lives. I rarely heard their stories. Protestors and veterans didn’t mix. The few times I did encounter veterans in the years after the war, I felt the same overwhelming despair I had in high school. What had we done in Vietnam, and what had we done to these young men who had served?

Decades later, I visited the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington DC, and was stunned by the sheer numbers of names on the wall. As I touched the letters chiseled into the granite, tears filled my eyes. So many lives lost.

I realized I was missing half the story of the war. All of us who were young at that time– protestors and those who served – were doing what we felt was right, whether that meant serving when called or trying to change our government’s policies. All of us were members of the same democracy, sharing a common identity as Americans.

After visiting the memorial, I had a sudden, almost gut-level need to find some of the Vietnam veterans who had come home, who had known the men and women listed on the memorial. I wanted to hear from the surviving vets – well, everything. How did they end up in the military? What was their year “in country” like? What issues had they faced? What buddies and friends had they lost, whose names were on the memorial? What had it been like after serving, to fit back – or not – into their civilian lives?

Hearing the stories of the veterans I interviewed could be hard; they were rough and painful, tender and challenging. These soldiers, after years of few people knowing about their time in Vietnam, were ready to talk. And they told me about challenges they’d faced that I’d only thought of in the abstract. The racial issues at home in the civil rights struggle played out in the military as well. When Henry Allen, an African American trained in nonviolence by Martin Luther King Jr., volunteered to do work around the base, he was given a wheelbarrow and told to collect human waste from the privies. The white volunteers were assigned to the trucks.

Another veteran, Japanese American David Oshiro, went out with American and South Vietnamese troops on a routine sweep the first day he was in Vietnam. Everyone wore tiger-striped jungle fatigues. Oshiro got shot through the neck, and when an American medic arrived he glanced at Oshiro laying on the ground and said to another soldier, “Don’t worry about the gook, we’ll get him later,” Oshiro pulled his dogtags out from under his shirt and thrust them in the air, yelling after him, “I’m an American!”

Despite the racism, bonds between the enlisted men ran strong, often transcending race. They were totally dependent on one another to survive. I heard several stories, but in my photo research I found the power of this brotherhood summed up in one image: a white medic giving a grievously injured African American medic mouth to mouth resuscitation, in a vain effort to save his life.

One of the most compelling issues I learned about was the challenge the men and women faced to their moral beliefs. We’ve all had our morality tested in small ways – given too much change, do you return it? But that most sacred belief – not to injure or kill another human being – is put on hold during a war.

Gilbert de la O, a tender and compassionate man, was devastated the first few times he saw suspected enemies killed. Then he reminded himself what he was taught in boot camp about the Vietnamese: “The Vietnamese people don’t value life, so to kill them is no biggie.” It was a classic way of dehumanizing the enemy.

Though there are reputed to be no atheists in a foxhole, I found the opposite could also hold true. Lily Jean Adams, an army nurse and dedicated Catholic, found herself questioning the very existence of god when she was confronted at the 12th Evacuation Hospital at Cu Chi with grievously wounded young Americans. If He did exist, how could He let this suffering happen? She hated seeing young men die on her watch and would bargain with God. “Not this one,” she would pray. “Not this one either.” And when a soldier died, she was “stuck between blaming God and asking for his help, his Grace.”

Returning to civilian life was a huge challenge for most of the veterans I interviewed. Jan Scruggs came back from Vietnam full of pain, remorse, and sorrow. In a booze-soaked night several years later, sitting at his kitchen table with flashbacks filling his mind, he decided he was going to build a memorial right in the middle of Washington DC with the names of all the American service men and women who had died in Vietnam. It would be his cry of protest and outrage about the way veterans had been forgotten. He worked tirelessly, using Maya Lin’s brilliant design, and got the Vietnam Veterans Memorial built in record time. It was the beginning of healing for our country, which was so deeply divided about the war, because all of us could agree to honor those who had died. We learned the wisdom in separating the war from the warrior.

All but one of the veterans I interviewed has visited the memorial. For each of them, it was cathartic. Only David Oshiro has never been. “To most people it’s names. Dead people,” he told me. “I always picture just eyes, eyes, eyes. I can’t have sixty thousand pairs of eyes staring at me.” I could never say it that eloquently, but it is a tribute to the power of the memorial.

These days, instead of running my fingers over the names of the war dead, I hear names on the radio of African American men shot by the police. I see the crawl scrolling on the bottom of my television screen, naming the victims of the latest school shooting. What toll will these shootings have on those who survived?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Once again, our democracy is being ripped apart. Though I find each violent incident incredibly sad, I am heartened by the protests, by those who take a knee, by the young adults who are saying, this isn’t right. Listen to us. Watch us sign up to vote. We’re committed to making a change.

I believe them. The brilliance of our democracy is that we have the right to hold our government accountable.

Meet Elizabeth Partridge

Elizabeth grew up in a bohemian family of photographers in the San Francisco bay area. She was taught to observe everything beautiful (her grandmother, Imogen Cunningham) and quirky (her father, Rondal Partridge), as well as the importance of bearing witness to social injustice (her godmother, Dorothea Lange). Elizabeth’s writing for young adults often mixes politics, social justice, photography, and music. Her book, This Land was Made for You and Me: The Life and Songs of Woody Guthrie, was a National Book Award Finalist, and Marching for Freedom: Walk Together Children and Don’t You Get Weary won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Young Adult Literature. Partridge lives and writes in an exuberant, messy three-generation household in Berkeley, California. Her latest book is Boots on the Ground: America’s War in Vietnam (Viking Children’s Books, Spring 2018). Find her at www.elizabethpartridge.com, on Facebook at www.facebook.com/elizabethpartridge, or on Twitter @epartridge.

Elizabeth grew up in a bohemian family of photographers in the San Francisco bay area. She was taught to observe everything beautiful (her grandmother, Imogen Cunningham) and quirky (her father, Rondal Partridge), as well as the importance of bearing witness to social injustice (her godmother, Dorothea Lange). Elizabeth’s writing for young adults often mixes politics, social justice, photography, and music. Her book, This Land was Made for You and Me: The Life and Songs of Woody Guthrie, was a National Book Award Finalist, and Marching for Freedom: Walk Together Children and Don’t You Get Weary won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Young Adult Literature. Partridge lives and writes in an exuberant, messy three-generation household in Berkeley, California. Her latest book is Boots on the Ground: America’s War in Vietnam (Viking Children’s Books, Spring 2018). Find her at www.elizabethpartridge.com, on Facebook at www.facebook.com/elizabethpartridge, or on Twitter @epartridge.

About Elizabeth’s new book, Boots on the Ground: America’s War in Vietnam

America’s war in Vietnam. In over a decade of bitter fighting, it claimed the lives of more than 58,000 American soldiers and beleaguered four US presidents. More than forty years after America left Vietnam in defeat in 1975, the war remains controversial and divisive both in the United States and abroad.

The history of this era is complex; the cultural impact extraordinary. But it’s the personal stories of eight people—six American soldiers, one American military nurse, and one Vietnamese refugee—that create the heartbeat of Boots on the Ground. From dense jungles and terrifying firefights to chaotic helicopter rescues and harrowing escapes, each individual experience reveals a different facet of the war and moves us forward in time. Alternating with these chapters are profiles of key American leaders and events, reminding us of all that was happening at home during the war, including peace protests, presidential scandals, and veterans’ struggles to acclimate to life after Vietnam.

With more than one hundred photographs, award-winning author Elizabeth Partridge’s unflinching book captures the intensity, frustration, and lasting impacts of one of the most tumultuous periods of American history.

For Amanda’s review of Boots on the Ground, hop on over here.

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

Review of the Day: My Antarctica by G. Neri, ill. Corban Wilkin

Exclusive: Giant Magical Otters Invade New Hex Vet Graphic Novel | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

It’s so sad that wars have existing in the 21st century