#SJYALit: Breaking Taboos, Telling Secrets, a conversation between Isabel Quintero and Elana K. Arnold

Introduction

In the introduction to Here We Are: Feminism for the Real World, Kelly Jensen writes, “What unites feminists is the belief that every person–regardless of gender, class, education, race, sexuality, or ability–deserves equality.” This intersection between multiple social justice movements characterizes what we call Third Wave feminism, a term coined in the 1990s, and it seems to be a unifying force right now in the resistance movement spreading across the US in response to the 2016 presidential election.

In the introduction to Here We Are: Feminism for the Real World, Kelly Jensen writes, “What unites feminists is the belief that every person–regardless of gender, class, education, race, sexuality, or ability–deserves equality.” This intersection between multiple social justice movements characterizes what we call Third Wave feminism, a term coined in the 1990s, and it seems to be a unifying force right now in the resistance movement spreading across the US in response to the 2016 presidential election.

But what does that have to do with books?

What makes a novel feminist?

In a series of conversations, four young adult authors–Amber J. Keyser, Elana K. Arnold, Mindy McGinnis, and Isabel Quintero–discuss what makes their recent books feminist and why they feel it’s important to give teen readers unvarnished reality in their fiction.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Today, April 20th — Elana K. Arnold and Isabel Quintero address reproductive rights and the power of depicting sex and abortion in fiction.

BREAKING TABOOS, TELLING SECRETS

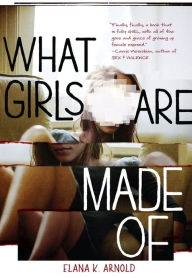

A conversation between Isabel Quintero, author of GABI: A GIRL IN PIECES, and Elana K. Arnold, author of WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF.

Elana: Isabel, I think it’s interesting that both of our titles–GABI: A GIRL IN PIECES, and WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF–hone in on how girls are dissected by themselves, by their families, by their friends and their boyfriends, by society. Why is it, do you think, that girls are such consumable products?

Elana: Isabel, I think it’s interesting that both of our titles–GABI: A GIRL IN PIECES, and WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF–hone in on how girls are dissected by themselves, by their families, by their friends and their boyfriends, by society. Why is it, do you think, that girls are such consumable products?

Isabel: Well, I think it has to do with the fact that we live in a capitalist patriarchy where we are taught that everything is consumable. Women are often not seen as autonomous, young women especially and girls less so. We are always thought of in relation to someone else, defined by what our purpose is in that relationship–daughter, sister, mother, girlfriend, mistress, wife, and so on. Those roles are seen as both consumable and disposable. And because we are often not seen as autonomous, as having our own worth, that seems to translate into our voices, our bodies, our time, being assumed to be in the service of others–for pleasure, reassurance, guidance, emotional support, nurturing, etc–and for their consumption.

Nina is girlfriend until Seth decides she is not, and doesn’t even tell her. Nina’s dad had one wife and disposed of her and then took on Nina’s mom. And in my book, Gabi’s mom feels Gabi should look a certain way because she needs to fill the role of desirable young woman to eventually become wife. Is she concerned that Gabi should go to college? Yes, but being desirable seems to take precedence sometimes.

Some of it may be rooted in fear. I know that one of my mom’s biggest fears is that I end up alone. And it has been this way since I was a teenager–being married was a top priority. Now that I am no longer with husband, I find that she still worries about that. But this goes back to having worth attached to how much we are worth to others–or, in other words, how much they can take.

I think this also speaks to the images of the different saints in your book. Those women were consumed and continue to be consumed by people as signs of true faith. Or am I wrong? Can you speak a little to how the saints are or are not being consumed? Why did you decide to include them?

Elana: Something that fascinates me about virgin martyr saints is the same as something that fascinates me about modern teenage girls: the ways they are consumed. The saints are first consumed by those who killed and dismembered them; then they are consumed again by the religion that says that their suffering marks them as holy; then they are consumed again and again each time their story of suffering, dismemberment, and death is told. As a writer, I am consuming them, as well, using their pain for my own artistic purposes. The little rhyme from childhood–Sugar and spice and everything nice, that’s what girls are made of–tells us straight up that girls are for eating. One of the reasons I love your Gabi is that she turns this paradigm upside down, eating rather than being eaten, consuming almost as an act of rebellion, getting bigger as a defense mechanism against being consumed.

Elana: Something that fascinates me about virgin martyr saints is the same as something that fascinates me about modern teenage girls: the ways they are consumed. The saints are first consumed by those who killed and dismembered them; then they are consumed again by the religion that says that their suffering marks them as holy; then they are consumed again and again each time their story of suffering, dismemberment, and death is told. As a writer, I am consuming them, as well, using their pain for my own artistic purposes. The little rhyme from childhood–Sugar and spice and everything nice, that’s what girls are made of–tells us straight up that girls are for eating. One of the reasons I love your Gabi is that she turns this paradigm upside down, eating rather than being eaten, consuming almost as an act of rebellion, getting bigger as a defense mechanism against being consumed.

Isabel: Interesting take on Gabi. I didn’t so much have her be a fat girl as a defense mechanism as much as just who she was–she likes to eat. Some of Gabi is based on me, and her being a fat girl is one thing. The thing about being fat is that it seems like an act of rebellion and it isn’t–the act of rebellion is loving your body and realizing that you have ownership of it. That no one else should have the right to shame you into self-hate.

Elana: I regret that I phrased this in this way–I know that Gabi isn’t fat as a defense mechanism. I do think that her eating and taking such pleasure in eating is a radical act, and something we rarely see in fiction–more often, the things we see girls consume are sex, alcohol, fashion. I totally agree with what you say about rebelling being the act of loving your body and realizing that you have ownership of it. The way Gabi consumes food does seem like an act of rebellion to me–it goes against expectations that she can enjoy food so much, or maybe that she’s so willing to tell us about the pleasure she gets from eating. Maybe this is because after eating comes digesting, and after digesting comes defecating, and we as a culture really don’t like to imagine our characters–female, particularly–as functioning bodies.

Another sometimes-function of the female body is pregnancy, and both your GABI: A GIRL IN PIECES and my WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF deal with the reasons around and the methods by which a girl might choose an abortion. When you began working on GABI: A GIRL IN PIECES, did you know that abortion would be part of the story you were telling, and what brought you to depict it in the particular ways you did?

Isabel: I actually always did know that abortion would be part of the book. Abortion is real. I say this because so many people seem to think that abortion is a new concept, that it is only a choice that women make in desperate times, and a choice that young women, teenage girls, cannot make. I think that women have always tried to find a way of not being pregnant because motherhood is not for everyone. I’ll say it again–motherhood is not for everyone. And women should have a say whether they are pregnant or not. When I was teen I knew girls who had abortions, in high school and at the university. For some young women it was tough because they felt they had no choice and were ashamed. For others they were so sure that they didn’t want a child but didn’t realize abortion was a real option and had tried other methods first, which is really dangerous and doesn’t guarantee success.

In GABI the abortion comes from a place of survival–if Georgina doesn’t have an abortion her father would surely beat her, thus her safety is in jeopardy. I wrote it in this way because it is a reality. Abortion and sex are not bad girl/good girl issues, they are simply realities of life. But I think this dichotomy harkens back to the notion of women as consumable–in which way do you want to be consumed? And also, asks men, (because this dichotomy only allows for heteronormative practices) what kind of woman would you like to consume? And that answer for some is the problem because it doesn’t allow women to avoid the male gaze at all.

What I appreciated about WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF was the fact that there is no moment of doubt for Nina. She is sure of her choice and what it means for her future. I really like that you gave her agency. That there was no one but herself who she had to answer to. But really what I liked is that you made her so real and flawed. This may be a strange question but do you think that there is difference between when straight cis-men write flawed female characters than when women do it? I think about this because my friend, author Erika Wurth, author of Crazy Horse’s Girlfriend, pointed out how women have had to learn to live in a man’s world, to see the world as men do, but the opposite is not true. I think it’s a very interesting idea and an important way of understanding how women are portrayed in literature.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Elana: I think that’s a really interesting question. I am a product of a late-nineties creative writing graduate school program and a high school education that told me that the reason the canon had so few women in it was because they just hadn’t produced work worthy of inclusion. I spent a lot of time trying to write like a man, and this applied most of all to the way I wrote about women and girls; I had so internalized the male gaze, both in my writing and in my life, that everything went through this filter. The work I have been doing in fiction and in life for the past ten years–especially the past five–has been focused on recentering girls and women: their experiences, their bodies, their emotions. WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF is peopled almost entirely with women, and it’s a story about female bodies, female shame, female desire, and female agency.

I think books like GABI: GIRL IN PIECES and WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF are incredibly important, especially in today’s political atmosphere, with women’s rights and female bodies being policed in so many truly frightening ways. I feel like we are watching the pendulum swing in the wrong direction–a regressive direction–and books like ours, and conversations like these, can be of service to young women. I’m grateful to you, Amber, and Mindy for our discussions, and to Teen Librarian Toolbox for the platform.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Elana K. Arnold (WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF) writes for and about children and teens. Some of her books have been included on the LA Public Library’s Best Books of the Year list, the Bank Street Best Book list, the YALSA “Best Fiction for Young Adults” list, have been ALAN picks, and have been selected for inclusion in the Amelia Bloomer Project (feminist books for young readers). Her last YA novel, INFANDOUS, won the Moonbeam Children’s Book Award and the Westchester Fiction Prize. She holds a master’s degree in Creative Writing/Fiction from the University of California, Davis, where she has taught Creative Writing and Adolescent Literature.

Elana K. Arnold (WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF) writes for and about children and teens. Some of her books have been included on the LA Public Library’s Best Books of the Year list, the Bank Street Best Book list, the YALSA “Best Fiction for Young Adults” list, have been ALAN picks, and have been selected for inclusion in the Amelia Bloomer Project (feminist books for young readers). Her last YA novel, INFANDOUS, won the Moonbeam Children’s Book Award and the Westchester Fiction Prize. She holds a master’s degree in Creative Writing/Fiction from the University of California, Davis, where she has taught Creative Writing and Adolescent Literature.

Isabel Quintero (GABI, A GIRL IN PIECES) is the daughter of Mexican immigrants. She was born, raised, and resides in the Inland Empire of Southern California. Gabi, A Girl in Pieces from Cinco Puntos Press, her first novel, is the recipient of the 2015 William C. Morris Award for Debut YA Novel, the 2015 Tomas Rivera Mexican American Children’s Book Award, the California Book Award Gold Medal for Young Adults, among others. Gabi has also been on several best of and recommendation lists, among them the Amelia Bloomer Project, Booklist, and School Library Journal. In addition to writing fiction, she also writes poetry and her work can be found in The James Franco Review, Huizache, The Great American Lit Mag, As/Us Journal, The Acentos Review, The Pacific Review, and others.

Isabel Quintero (GABI, A GIRL IN PIECES) is the daughter of Mexican immigrants. She was born, raised, and resides in the Inland Empire of Southern California. Gabi, A Girl in Pieces from Cinco Puntos Press, her first novel, is the recipient of the 2015 William C. Morris Award for Debut YA Novel, the 2015 Tomas Rivera Mexican American Children’s Book Award, the California Book Award Gold Medal for Young Adults, among others. Gabi has also been on several best of and recommendation lists, among them the Amelia Bloomer Project, Booklist, and School Library Journal. In addition to writing fiction, she also writes poetry and her work can be found in The James Franco Review, Huizache, The Great American Lit Mag, As/Us Journal, The Acentos Review, The Pacific Review, and others.

Further reading

Amanda’s review of Gabi, A Girl in Pieces

Amanda’s review of What Girls Are Made Of

Filed under: #SJYALit

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

In Memorium: The Great Étienne Delessert Passes Away

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT