#SJYALit: From Aberrant Girl to Nasty Woman, a conversation between Elana K. Arnold and Amber J. Keyser

Introduction

In the introduction to Here We Are: Feminism for the Real World, Kelly Jensen writes, “What unites feminists is the belief that every person–regardless of gender, class, education, race, sexuality, or ability–deserves equality.” This intersection between multiple social justice movements characterizes what we call Third Wave feminism, a term coined in the 1990s, and it seems to be a unifying force right now in the resistance movement spreading across the US in response to the 2016 presidential election.

But what does that have to do with books?

What makes a novel feminist?

In a series of conversations, four young adult authors–Amber J. Keyser, Elana K. Arnold, Mindy McGinnis, and Isabel Quintero–discuss what makes their recent books feminist and why they feel it’s important to give teen readers unvarnished reality in their fiction.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Today, April 4th — Amber J. Keyser and Elana K. Arnold take on “unlikeable characters” and the evolution from aberrant girl to nasty woman.

April 11th — Mindy McGinnis and Amber J. Keyser talk about barriers. What happens when a girl smashes up against society’s expectations for what a girl should be?

April 20th — Elana K. Arnold and Isabel Quintero address reproductive rights and the power of depicting sex and abortion in fiction.

FROM ABERRANT GIRL TO NASTY WOMAN

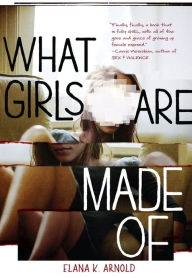

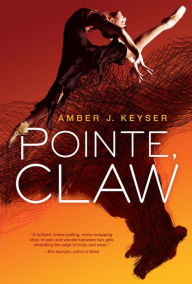

A conversation between Elana K. Arnold, author of WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF, and Amber J. Keyser, author of POINTE, CLAW.

Amber: I notice that many book reviews that highlight the feminist aspects of a novel usually include a shout-out to an “unlikeable” female character. What does that term mean to you? Does it apply to Nina in WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF?

Amber: I notice that many book reviews that highlight the feminist aspects of a novel usually include a shout-out to an “unlikeable” female character. What does that term mean to you? Does it apply to Nina in WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF?

Elana: I find the whole idea of “unlikeability” to be fascinating. Ultimately, I think that when someone labels a character as “unlikeable,” that actually tells us a whole lot more about the reviewer/reader than it does about the character. To me, the term “unlikeable” means that the reader has likely reduced a complicated, multifaceted character down to just some of her parts– the reader has decided that some of the character’s qualities, actions, or characteristics tell her whole story. It infuriates and fascinates me that we as a culture ascribe a narrower bandwidth of “likeablity” to females than we do to males. I have no doubt that there will be some readers who find Nina to be unlikeable. I think it’s more interesting to think about how her actions and perspectives make us feel–both the actions and perspectives we like and those we don’t like (which may be different from reader to reader). I think it is interesting to sit in discomfort and pull it apart, wonder at it, and come to terms with it. We can learn a lot about ourselves that way.

Amber: I’ve been thinking about Nina in your book, Dawn in mine, and other characters (like those in THE WALLS AROUND US by Nova Ren Suma) labeled as “unlikeable.” I agree with you that “unlikeable” tends to be pinned on girls and women who express rage, desire, jealousy, and other feelings that aren’t considered nice or seemly. And you’re right that men get to express a wider range without being labeled as aberrant, and if they are white, upper class men even abhorrent behavior gets excused away (case in point: Stanford rapist Brock Turner). You also said we learn about ourselves by looking at those boundaries between nice and unlikeable. When society and the books that reflect it, shy away from the full range of emotions that women can and do experience, I’m afraid that girls learn to self-censor their “unacceptable” emotions. Psychic hurt happens when we cram ourselves into a cookie cutter version of “girl.”

Elana: Amber, your POINTE, CLAW is about two powerful girls whose strengths are in some ways parallel and in some ways very different. And the title, the way both words can be either a thing (a pointe shoe, a claw) and an action (to point, to claw) works as such a brilliant metaphor for the girls. Both of your characters are outliers; they are extreme, in various ways. Many young women spend lots of effort filing away at the parts of themselves that reveal them to be outliers, to be strange, to be different. Did you intend to create such intense protagonists?

Amber: POINTE, CLAW comes from a place of deep pain and anger, which spawned the intensity in its pages. Ballet was everything to me from sixth grade through high school. I dreamed of dancing for Joffrey or New York City or American Ballet Theater. My entire identity was woven around being a dancer. When my career crashed (for complicated reasons), I was devastated and became quite self-destructive. My body, no longer dancing 4-6 hours a day, changed radically. My social circle evaporated. I didn’t even feel like I belonged in my own family. The feeling of being betrayed by my body, my ballet family, my friends, and my own dreams fuels POINTE, CLAW. In the book, Jessie and Dawn are definitely extreme in different ways, but both have ravenous and unseemly desires. They want touch and sex and wildness and to break free from constraints. When everything they know starts to crumble around them, their response is to burn hotter, to go supernova instead of being crushed.

Elana: And do you think that intensity is reflective of the way young women are feeling right now, in this cultural moment?

Amber: Honestly, I hope so. Politically, those in power are doubling down on the constraints on women. The message to women and girls is chilling: Your body doesn’t belong to you. Don’t exist outside of the lines we have drawn for you. Be nice. Be grateful for what men do for you. I am absolutely rage-filled most of the time. I hope that younger women are too. I’ll be the first one to hand them a flame-thrower. I’m curious what you think about this. Is a through-line from unlikeable characters to today’s surging activism?

Elana: I do think so. I have spent much of my life being afraid of authority. Truthfully, I am still terrified of a man in a uniform, even though my white-presenting privilege has meant that all of my actual interactions with uniform-wearing men have been relatively safe, though often tinged with an unwelcome undercurrent of sexual tension. I began writing WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF three years ago, and I completed the final draft nearly a year ago, so it was well in advance of the rise of Trump and the rage that has grown in me along with that. This is an angry book, so clearly I was sorting through all sorts of anger, but I think my anger then was more woven through with shame and self-flagellation, an attempt to both punish and forgive myself for sins real and imagined. Now, my anger burns hotter; it’s a white-hot anger, and I’m not going to spend more time being angry at myself for past complicity in a system of repression that eats women up. I think (I hope) that girls are done apologizing for being girls, for being in possession of unlikeable characteristics and emotions. I think so many girls are ready to fight, and I think books that show characters mobilizing and rising up are important and affirming. A book like yours, Amber, is a flame-thrower. But it doesn’t read like an instruction manual or a manifesto; it reads like what it is, a brilliant and tightly-crafted novel. How do you walk the line between telling a good story and writing to inform, convince, or conflagrate?

Amber: For me, each novel starts with a big question or theme that I don’t fully understand. I am writing toward a better understanding of the topic I’m exploring. That’s very different from starting with “this is the truth I know, which I will now present to you.” I hope that allows me to avoid being a pedantic bore. What about you? You mentioned writing your way through a complex stew of anger, shame, and self-flagellation. I am wondering how the process of writing a novel like WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF changes you.

Elana: Some books are a pleasure. Others feel like the painful extraction of a tumor with long, winding, grasping roots. WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF belongs to that second category. This book, like many, began with a feeling and, in this case, a first line–When I was fourteen, my mother told me there was no such thing as unconditional love. That idea of love–the conditions of being lovable, and the conditions under which we give our love (to others, to ourselves, to a concept or a cause, like God or religion)– fascinates me. Writing WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF gave me a place to sort through how I felt about love, and my own value. As a young woman, I really felt that if someone liked or desired me, it was my obligation to give that person some part of me–access to my body, or a smile and laugh even if the attention felt uncomfortable or unasked for, things like that. Writing this book felt like a chance for me to examine my assumptions about that and many things, and to declare that, no, actually, I don’t want to behave that way anymore. And I don’t have to. It’s not my job to make other people comfortable. What a revelation! In POINTE, CLAW, your Jessie and Dawn seem to grapple with a similar question–how much access and control do they owe other people over their bodies? And how are they “supposed” to interact with/feel about their bodies? Can you talk about your characters’ relationships with their flesh?

Amber: While I was revising POINTE, CLAW, I went to an incredible writing workshop with Lidia Yuknavitch (author of THE SMALL BACKS OF CHILDREN and A CHRONOLOGY OF WATER). She is focused on what she calls corporeal writing, meaning writing from the body, in the body, through the body. Again and again during the workshop, she posed questions that linked body and emotion. Where does shame live in your body? Where does anger live in your body? Where does vulnerability live in the body? One of the big ideas I wanted to write about in POINTE, CLAW was the contrast between inhabiting the flesh and dissociating from it. There is such stigma about the female body–periods, fat, body hair, smell, orgasm–I think women often struggle to be in the body. Jessie certainly does. She is constantly watching herself in the mirror and trying to fit the image of perfect. It’s a weird out-of-body existence. When she loses that distance during the dance with Vadim, it freaks her out because it represents such unbridled sensation. Dawn is caught between fighting and embracing the chaos of her own flesh. Ultimately being in the body is a way to claim power. There’s a quote from Mary Oliver that captures something important about both our books–Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life? To finish up our conversation here, can you talk about how this quote relates to WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF?

Amber: While I was revising POINTE, CLAW, I went to an incredible writing workshop with Lidia Yuknavitch (author of THE SMALL BACKS OF CHILDREN and A CHRONOLOGY OF WATER). She is focused on what she calls corporeal writing, meaning writing from the body, in the body, through the body. Again and again during the workshop, she posed questions that linked body and emotion. Where does shame live in your body? Where does anger live in your body? Where does vulnerability live in the body? One of the big ideas I wanted to write about in POINTE, CLAW was the contrast between inhabiting the flesh and dissociating from it. There is such stigma about the female body–periods, fat, body hair, smell, orgasm–I think women often struggle to be in the body. Jessie certainly does. She is constantly watching herself in the mirror and trying to fit the image of perfect. It’s a weird out-of-body existence. When she loses that distance during the dance with Vadim, it freaks her out because it represents such unbridled sensation. Dawn is caught between fighting and embracing the chaos of her own flesh. Ultimately being in the body is a way to claim power. There’s a quote from Mary Oliver that captures something important about both our books–Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life? To finish up our conversation here, can you talk about how this quote relates to WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Elana: What I want to do with this one wild and precious life (one of the things I try to do) is to tell stories that make me uncomfortable and scared, that shake my center, that help me understand how I feel about my own past, humanity, society, religion, death, bodies… all the stuff that I wrestle with. I am a selfish writer when it comes to my books about teens. When I write for younger readers, I do consider the kids who might pick up the book one day, but when I work on a book about teens, there is no reader in my sights. I work through the story the way one might rub at a cavity with her tongue, exploring the pain, experiencing the rough edges. The longer I work as a writer, and the older I get, the more honest I am in my writing, and the deeper I am willing to go into my own fear, inhibition, and anger. Of course, when the book is finished, then I become sharply aware of the possibility that it will be read. I hope that WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF can help put into words what young woman may be feeling about their bodies, their positions in society, their relationships, their loves. And if books like POINTE, CLAW and WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF give readers words that spur them to action, all the better! The world needs fierce women– Go, girls, rise up and roar.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Amber J. Keyser (POINTE, CLAW) is the author of THE WAY BACK FROM BROKEN (Carolrhoda Lab, 2015), a heart-wrenching novel of loss and survival, which is a finalist for the Oregon Book Award, and THE V-WORD (Beyond Words/Simon Pulse, 2016), an anthology of personal essays by women about first-time sexual experiences, which was selected for the New York Public Library’s Best Books for Teens 2016, the Chicago Public Library’s Best Nonfiction for Teens 2016, the Rainbow List, and the Amelia Bloomer List. Find out more about her work at www.amberjkeyser.com and @amberjkeyser.

Amber J. Keyser (POINTE, CLAW) is the author of THE WAY BACK FROM BROKEN (Carolrhoda Lab, 2015), a heart-wrenching novel of loss and survival, which is a finalist for the Oregon Book Award, and THE V-WORD (Beyond Words/Simon Pulse, 2016), an anthology of personal essays by women about first-time sexual experiences, which was selected for the New York Public Library’s Best Books for Teens 2016, the Chicago Public Library’s Best Nonfiction for Teens 2016, the Rainbow List, and the Amelia Bloomer List. Find out more about her work at www.amberjkeyser.com and @amberjkeyser.

Elana K. Arnold (WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF) writes for and about children and teens. Some of her books have been included on the LA Public Library’s Best Books of the Year list, the Bank Street Best Book list, the YALSA “Best Fiction for Young Adults” list, have been ALAN picks, and have been selected for inclusion in the Amelia Bloomer Project (feminist books for young readers). Her last YA novel, INFANDOUS, won the Moonbeam Children’s Book Award and the Westchester Fiction Prize. She holds a master’s degree in Creative Writing/Fiction from the University of California, Davis, where she has taught Creative Writing and Adolescent Literature.

Elana K. Arnold (WHAT GIRLS ARE MADE OF) writes for and about children and teens. Some of her books have been included on the LA Public Library’s Best Books of the Year list, the Bank Street Best Book list, the YALSA “Best Fiction for Young Adults” list, have been ALAN picks, and have been selected for inclusion in the Amelia Bloomer Project (feminist books for young readers). Her last YA novel, INFANDOUS, won the Moonbeam Children’s Book Award and the Westchester Fiction Prize. She holds a master’s degree in Creative Writing/Fiction from the University of California, Davis, where she has taught Creative Writing and Adolescent Literature.

UPCOMING EVENTS

You can catch Amber and Elana on tour together during April and May. Events are scheduled in Seattle, Portland, the Bay Area, Davis, L.A., and Orange County. More details here: http://amberjkeyser.com/appearances/

Further reading

Amanda’s reviews of Pointe, Claw and What Girls Are Made Of

Filed under: #SJYALit

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Happy Poem in Your Pocket Day!

This Q&A is Going Exactly As Planned: A Talk with Tao Nyeu About Her Latest Book

More Geronimo Stilton Graphic Novels Coming from Papercutz | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT